5 Reasons to (Finally) Read 1776

With our country’s anniversary drawing near, we’re offered an opportunity to go back in time within these pages.

All book lovers know the happy dilemma of having too many books.

Many of us are blessed with shelves and shelves of volumes that we intend to read one day. There are so many—it could be a long time!—but no, we are not donating them. How dare you suggest such a thing?

We’re not donating them, but we haven’t read them yet, either. The reason is simple: We have several other books to choose from. (For the record, few book lovers understand the order in which they choose their own reads. It has little to do with the order in which the books were purchased.)

It has been said that a book is a friend—and that the friend is aware. A book will always tell you when the time has come to enjoy it.

(The quotes in this post are all from 1776.)

Owned, but not read…

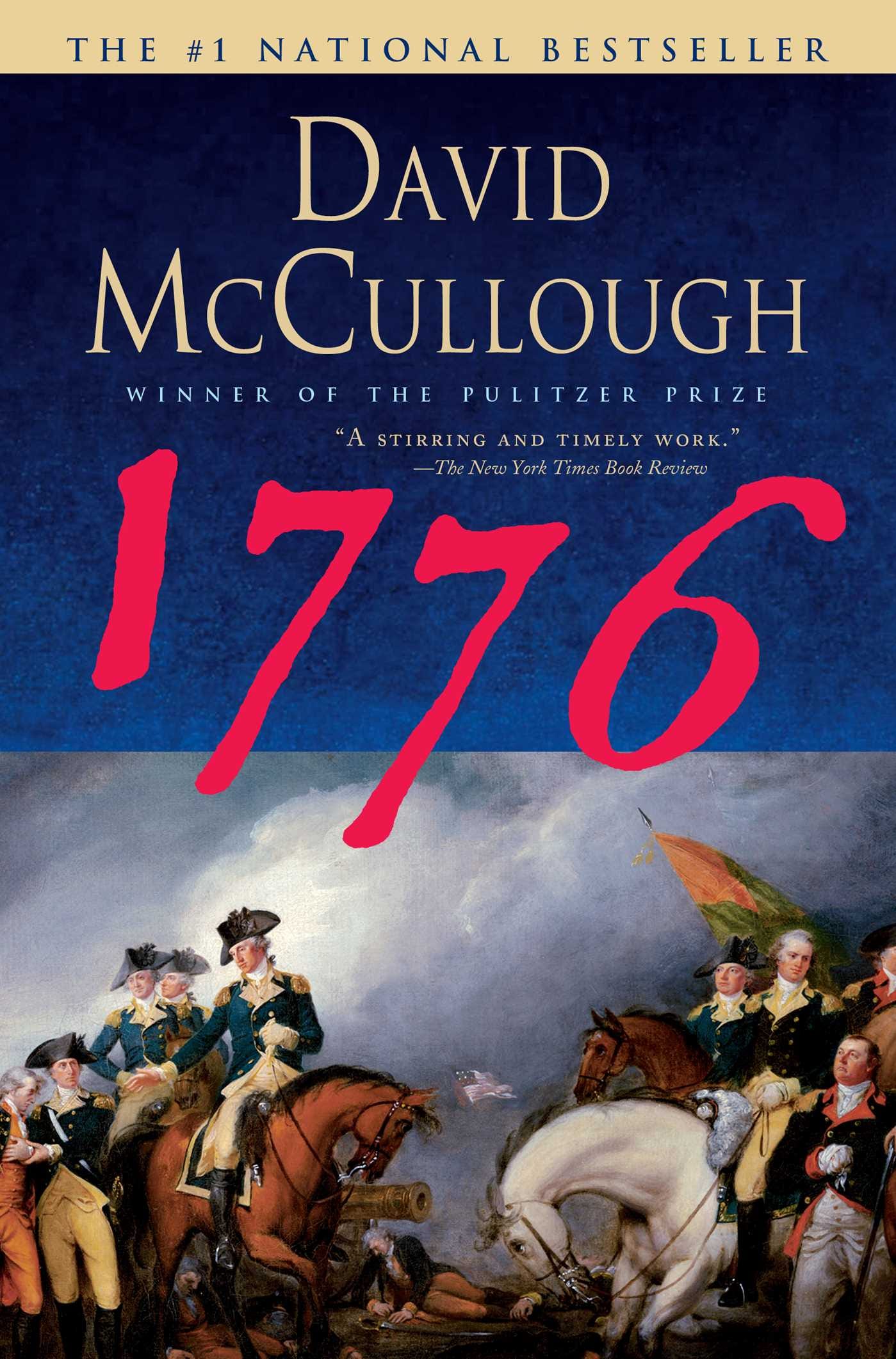

This year, I was beckoned by the book 1776 by David McCullough. I remember purchasing it long ago, soon after it was published. I purchased it in the spirit of “Everyone is buying it. Therefore, it must also be on my shelf.”

The risk with this mindset, is that such books can end up on the “Owned but Not Read” shelf.

This year was my time to read 1776. It didn’t take as long to get through as I thought, and I knew halfway through that it didn’t deserve to be in the “Owned but Not Read” shelf.

It is an important story, especially now that we are nearing the 250th anniversary of our country. Now that I have, at last, finished this book, I understand why it’s been so popular (for those who’ve actually read it).

It isn’t only important for Americans. The story is so surreal that I’m sure everybody would enjoy it.

If you need five reasons to read 1776, here are my suggestions. (I’m aware that six reasons would make more sense, but for the sake of post length, we’ll limit it.)

If you are on the fence, maybe a couple of these points will compel you to reach for the book!

1- It tells about ordinary soldiers.

This year, during my journey exploring early American history, I’ve been reading a lot of biographies about the Founding Fathers.

These were obviously not ordinary men, with many born into some form of privilege. They tended to be wealthy in land and well-educated. Even gentleman-farmers did not get sweaty. Jefferson owned farms, but slaves took care of the hard work.

1776 does mention these men. How could we tell this story without them? However, they do not overshadow the ordinary soldiers. This book honors the common men who fought and died for that cause, which I appreciated.

McCullough helps us to see that war from the viewpoints of working husbands and fathers. There is a special greatness about those who signed up to fight, knowing that they were imperfect and unprepared—and might lose their lives.

McCullough makes a point of “showing” us how precarious the matter was for these men and their families. In the following passage, he recounts how British commanders Burgoyne and Percy dismissed them as ‘peasantry,’ ‘ragamuffins,’ and ‘rabble in arms’:

That so many were filthy dirty was perfectly understandable, as so many, when not drilling, spent their days digging trenches, hauling rock, and throwing up great mounds of earth for defense. [...] It was dirty, hard labor, and there was little chance or the means ever to bathe or enjoy such luxury as a change of clothes.

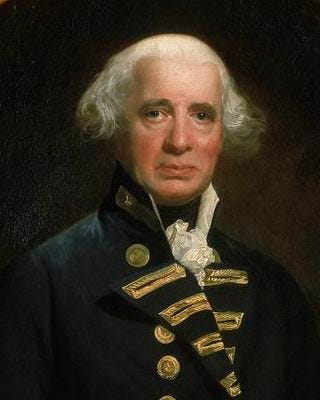

2- It introduces us to King George III.

In many books about this war, King George III is mentioned in passing. It’s not hard to imagine why; after all, he didn’t do the fighting.

1776 was the first book I’ve found in which the author troubled himself to introduce the human who was king.

King George III was more than an ominous figure feasting in the background. The following paragraph helps us to “see” him:

George III had a genuine love of music and played both the violin and piano. (His favorite composer was Handel, but he adored also the music of Bach and in 1764 had taken tremendous delight in hearing the boy Mozart perform on the organ.) He loved architecture and did quite beautiful architectural drawings of his own. [...] He avidly collected books, to the point where he had assembled one of the finest libraries in the world.

It’s important to know about the king. Knowledge of King George III provides contrast, which in turn helps us understand George Washington.

Much has been made of the fact that the two rivals were called George. Many think it fate that the George who won did not have natural children; therefore, no American royal line followed.

This balance makes the story more poignant and exciting.

3- It mentions an imperfect Washington.

George Washington is famous for having been able to maintain calm in impossible situations.

We remember him as being forever in control. I believe this does him a disservice—he was also human. There were times when he lost his patience; how could he not?

George Washington had been placed in charge of young, untrained, undisciplined soldiers. He needed to mold them into an army that could defeat an empire. Given those circumstances, there were surely instances when he felt fear.

During the battle at Kips Bay, he rounded on his soldiers, overcome with anger:

It was everything he had feared and worse, his army in pellmell panic, Americans turned cowards before the enemy.

In a fury, he plunged his horse in among them, trying to stop them.

Cursing violently, he lost control of himself. By some accounts, he brandished a cocked pistol. In other accounts, he drew his sword, threatening to run men through. “Take the walls!” he shouted. “Take the corn field!” When no one obeyed, he threw his hat on the ground, exclaiming in disgust, “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?”

There were also times in which Washington was a source of courage. He knew that, in spite of the odds, these men had enlisted. They were imperfect, yet chose to risk their lives.

During another battle, his presence stirred a different spirit:

The sight of Washington set an example of courage such as he had never seen, wrote one young officer afterward. “I shall never forget what I felt ... when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him. Believe me, I thought not of myself.

“Parade with us, my brave fellows,” Washington is said to have called out to them. “There is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly!”

4- It’s truthful about human fear.

It’s said that hope is the last thing to die. We would like to believe that the rebels were always ready to fight. When provided with context, we can understand why this was not so.

Rebel towns were under siege from an experienced army of men, professed soldiers. They were prepared tactically; they had the motivation of decent pay. When Hessian soldiers arrived to assist the British, even the British shook their heads at Hessian savagery.

American men continued to die or become grievously wounded. Towns were raided, women and children brutally attacked. As victory seemed less and less likely, people grew desperate. They wished to ensure the safety of their families.

This safety seemed to arrive at last, when Admiral Lord Howe presented a proclamation on behalf of the King. It offered “free and general pardon” to all who, within sixty days, would take an oath of allegiance and “peaceful obedience.”

Those who took such an oath would:

reap the benefit of his Majesty’s paternal goodness, in the preservation of their property, the restoration of their commerce, and the security of their most valuable rights, under the just and most moderate authority of the crown and Parliament of Britain.

In New Jersey, thousands eventually flocked to take the oath. It seemed the prudent choice, a way to ensure safety.

Astonishingly, Washington’s army held out. In spite of the flickering nature of their hope, the Treaty of Paris was eventually signed, ending the war.

5- 1776 was just the start.

The war did not end until 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. During those years of tumult, the rebels suffered losses and gains. There is so much to write about during the years in between.

I’ve written about Benjamin Franklin, whose influence in France offered us great advantages. I’ve read about the frustrations of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, as they tried to forge alliances with other nations.

1776 wasn’t the only notable year of the Revolutionary War. It was the time when ordinary men—farmers and shopkeepers by profession—decided to risk it all. They went forth to fight an enemy that was much bigger than them.

McCullough’s book, 1776, tells their stories with sparkling prose. It offers vivid pictures of men and women who realized that better lives were possible.

If you are on the fence about reading it, I hope that this review can sway you.

David McCullough was an excellent author. Though this was one of his shorter books, it tells an important story.

Nearly 250 years later, the spirit of 1776 is alive. With our country’s anniversary drawing near, these pages offer an opportunity to go back in time. It’s an opportunity to celebrate, learning about 1776—how it started, and why it is worth fighting for to this day.

Have you read this book? If so, what do you think about my points? Feel free to comment and start a conversation!

Posts I loved on Substack this week:

Read this years ago, now I’m wanting to read it again.

Very cool! Definitely quite a contrast from the endless cliches about king George being “mad.” You always find new ways to introduce books, which is refreshing.