A Tribute to Mary, Mother of George Washington

I imagine that the dying Mary Washington believed her son had become a king. ‘What a good king he will be,’ she must’ve thought.

One might be tempted to think that, behind every strong leader, there stood a good parent. I wouldn’t say that’s true in every situation; plenty of people in history have had to build themselves up. Perhaps they were orphaned; perhaps their parents were cruel, unworthy of the title mother or father.

My post last Wednesday was about Maria Brontë, mother of the three authors we know and love. It was by accident that the woman I selected for today’s post turned out, also, to be a mother. Perhaps she wasn’t the mother of an author (well, technically she was—if her son’s journal entries and declarations count).

Today I want to talk about the mother of George Washington, Mary Ball Washington.

I recently found a book about her by scrolling the rabbit hole of Amazon. I confess to feeling guilty that I’d never thought about her before. Having lived a quiet and, frankly, unexciting life, Mary Ball Washington left few traces of herself or the things she did (aside from birthing the Father of the Nation). Volumes have been written about her son, yet Mary remains a mystery.

We should not feel too guilty about this ignorance. The truth is, there is little to know her by. She lived so long ago that her homes have either been destroyed or heavily renovated. Most of her letters are lost, and we can’t put too much faith in any one account of what she was like.

For example, one of her grandsons claimed she never sat for a portrait—yet a portrait exists that has been dubbed the likeness of Mary Ball Washington.

Mary struck me as another woman who was swallowed by history—one who deserved a mention, even if facts about her are scant. She did not write a book; indeed, her education was limited, as ladies in those days were not taught the same skills as their brothers. Her surviving letters are riddled with spelling errors.

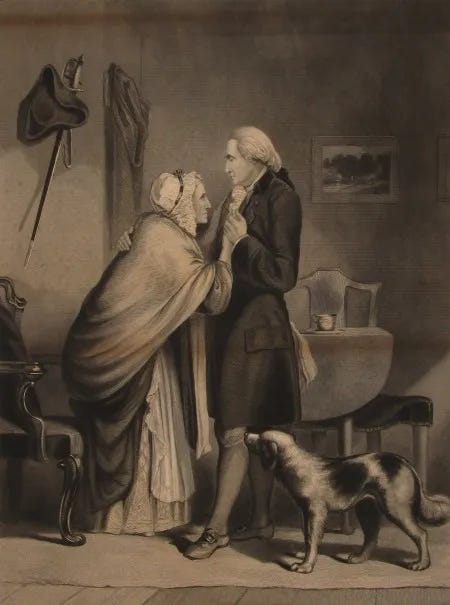

She did not write a book, but she gave birth to a son who would go on to become our first President. Though it is not known what sort of a mother she was—some witnesses described her as a disciplinarian, with George referring to her as madam—she unknowingly contributed in the changing of the world she lived in.

Mary’s grandfather crossed the ocean from Britain to Virginia when things were “going steady.” She, in turn, was brought up to love her British heritage. Some people speculate that Mary was opposed to the idea of a revolution; in her opinion, a total break from England was not necessary. She thought it could be “worked out” some other way.

As a mother, Mary Ball Washington is described as having been harsh and strict on George. She might have inadvertently given him qualities he would need later. He was to be a general; surely his mother’s ways of discipline were cemented into his being, enabling him to endure harsh battles.

Like mother, like son—in some things, anyway.

Fiction is unkind to her. I recently read Mount Vernon Love Story by Mary Higgins Clark, and while I did enjoy the book (check out my review!), Mary Washington is portrayed as a woman with such a hard heart that George regards her as the enemy. There is an instance (based on truth) where Mary opposes George’s desire to become a sailor.

I understand her reluctance: movies have painted life at sea as an adventure. In truth, it was not at all glamorous for a new sailor. Newbies were bullied, mocked, or worse by experienced “men” who, bored on a ship, sought entertainment in such activities.

In Higgins Clark’s book, Mary approves at first of George’s dream; she even gives her son a trunk to take during his travels. Later, she sends a letter to her brother in England, who writes back and convinces her against this endeavor. Without a second thought, she takes the trunk away, putting an end to it all.

There are no coincidences, though; George was destined for greater things than the life of a sailor.

If we take a closer look at Mary’s life before she became a mother, we can muster sympathy for her, too.

Mary Ball’s place of birth is debated: it was either at her family’s plantation in Epping Forest in Virginia, or at a different plantation near Simonson, also in Virginia. She was the only child of Col. Joseph Ball (1649-1711) and his second wife, Mary Johnson Ball (1672-1721). Her paternal grandfather, William Ball (1615-c. 1689) had left Britain in the 1650s.

Her father died when she was three years old. Her mother died when she was around twelve. She was sent with a guardian, who also died shortly after. Eventually she was entrusted to the care of George Eskridge, the brother of a Jane Washington. It is through George Eskridge that she would meet the widower Augustine Washington. The two married on March 6, 1731, when Mary was twenty-three.

Augustine Washington already had two sons from his previous marriage, both of whom were at school in England. His story was tragic, but not uncommon for the time: he’d sailed to England in order to visit his sons and conduct business. When he returned, he discovered that his first wife, Jane Butler Washington, had died. It was not long after her death that George Eskridge arranged for him to meet Mary Ball. It was an advantageous match; by the standards of the day, Mary was wealthy. She had inherited a great deal of property.

Mary and Augustine were a content, hard-working couple. They settled at Ferry Farm, managing plantation affairs and adding to their family along the way. Mary and Augustine’s children included George (1732-1799), Elizabeth (1733-1797), Samuel (1734-1781), John Augustine (1736-1787), Charles (1738-1799), and Mildred (1739-1740).

Unfortunately, Augustine Washington died five years into their marriage, on April 12, 1743. Once more, Mary found herself alone and grieving—but now she had a plantation and several properties to manage. She had not been educated for that sort of work. Could the sudden stresses added to her load have contributed to her being an “unkind” mother?

While some acquaintances described Mary as cold, others recalled her as an anxious woman. She must have experienced psychological consequences after so many losses. Not only had she lost her parents, guardian, and husband—she also lost many homes that had become dear to her.

Mary clung to Christian faith as an anchor. It steadied her through an uncertain life. She was active in her Anglican parish, raising all of her children in the same tradition.

What must her thoughts been when, after the war, her son George was compelled to renounce Anglicanism? He no longer held to the politics of England. Anglicanism being closely tied to those politics, he could not continue worshiping as one of them.

Mary must have grieved when he joined a different church, widening the void between mother and son.

In spite of their differences, Mary did love her son. She had been afraid to let him go to sea as a sailor; when he became a general instead, she went to the same spot on her property every day to pray. It’s a lovely hollow amongst trees and rocks. This spot has been memorialized with a plaque calling it Meditation Rock. It didn’t matter the weather, nor did it matter that George was acting against her personal beliefs: she was his mother, and she prayed until the war ended.

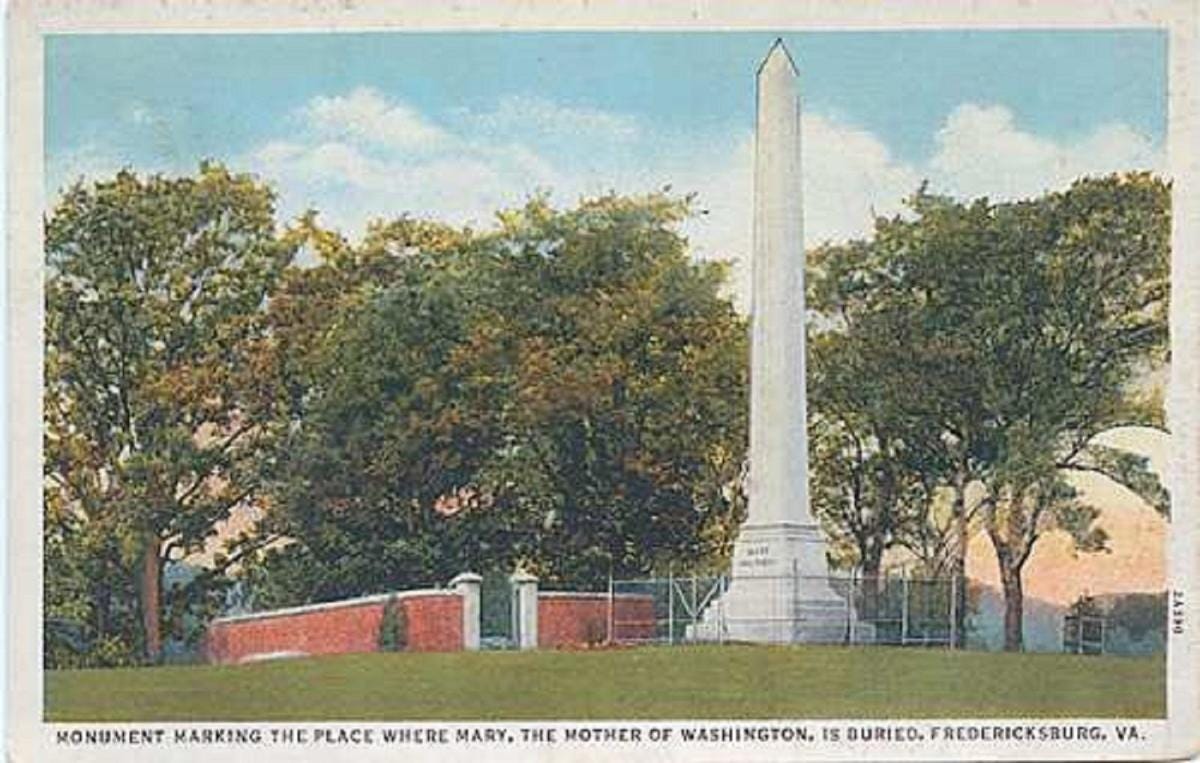

Another monument was later erected in her honor. It is a smaller version of the Washington Monument in D.C. Read its fascinating history here. Silas Burrows, a New York philanthropist, was commissioned by Andrew Jackson to build her a memorial—but Burrows’ death left the project unfinished. It was abandoned for many years, an obelisk lying forgotten on the ground.

When it was reported in 1862 that troops were using the monument for target practice, local women decided to take action. In 1899, two preservationist groups raised sufficient funds to purchase the land on which the monument would stand. It might be the first instance in which women became involved in the construction of a monument. Women also played an active role deciding how it would look; they debated and planned until the finished work stood in all of its glory.

It was completed in 1894 and dedicated by President Grover Cleveland. Having been a project carried out by women for a woman, it bears the inscription, “Erected by her Country-women.”

Learn more about Mary Washington at the Mount Vernon website!

I didn’t plan to write two posts about mothers. Last week’s post featuring Maria Branwell Brontë had a different tone: I can tell off the bat that Maria and Mary (the names are coincidences too!) were different in how they brought up their children. Furthermore, Maria did not live to see her youngest daughter become a lady. Mary Ball Washington was alive to witness George’s evolution as he carried out his duties.

Let us move away from the image of Mary Ball Washington as strict and unkind. Instead, let us evoke in our minds the image of a mother kneeling at Meditation Rock, praying that her son would survive his next battle—praying that she would see him again, even if she was unable to offer the maternal affection she never received.

In 1789, while the elderly Mary suffered from painful breast cancer, George was elected President. Mary did not know what “being President” meant; in her ailing state, could she even think clearly? As her consciousness flickered and she prepared to meet the God she loved, I imagine that Mary took being President to mean her son had become a sort of king. What a good king he will be, she must have thought.

Mary Ball Washington died on August 25, 1789, at the ripe age of 80. I think it is safe to say that she loved, and was proud of, her son.

Long live the United States, and long live parents—by blood or adoption—who do what they can to bring up strong children. Some become authors; others, Presidents. Most of us will live smaller lives, but they are no less significant. We might not all become President, but we are given opportunities to change the world by our acts of kindness.

Will I write about another mother in the coming weeks? Who is it that will tap my shoulder and ask that I tell her story? I can’t wait to find out.

Thank you for reading my post! Please comment with your thoughts, or with any corrections you might wish to make on my writing; I love critique. It is how a writer and amateur historian grows.

Is there a historical figure you’d like to know more about? Feel free to offer a few names that I can consider for research!

The Mother of the Brontës: When Maria Met Patrick

Maria Branwell’s legacy has come to be her daughters. The wise and fierce words of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë burn in the world as brightly today as when they were written.

I am so enjoying your wonderful posts about historical figures! I am learning so many new things 😊🤍

Fantastically detailed and yet concise. Only you could do it!