Anne Bradstreet: America’s First Poet

This woman made a contribution, using her words to give the colonies dignity, at a time when women were considered incapable of writing poetry and prose.

In the centuries since its discovery in the 1400s, America has taken many shapes. It’s brought forth grand ideas and been the scene of countless battles. Such progress did not spring forth overnight.

So much has changed that the settlers who built their first homes in this land would not recognize it now.

The Mayflower and ships like her were filled with travelers. Most were Puritans dedicated to their strict but peaceful way of life. This was the reason for their move: in England, Puritans endured persecution and mockery from the Anglican church and other sects. They lived their faith differently: rejecting tradition, they chose instead to live by tenets stated explicitly in the Bible.

In response to the persecution, some Puritans escaped to Holland and rebuilt their lives there. Others, however, chose a more perilous journey to an untamed world. Little was known about America except that it was vast, wild, and (they assumed) a place where they could start anew, worshiping God as they pleased.

This post isn’t about Mayflower, but the story began on a different ship called Arbella. It is the story of a woman who sailed with her family across the ocean to America. Once there, they planned to build a freer life in New England.

Though Puritans rejected the Church of England, they considered themselves English. (Families that settled in Holland began to feel regret, when their children grew up acting more Dutch than English). English Puritan ministers urged their flocks to seek freedom in the New World. They could cultivate a society free of sin in which virtue would reign.

Among the families traveling on Arbella were the Dudleys and the Bradstreets. The woman who inspired this post was born Anne Dudley; after marriage, she took the surname of Bradstreet.

Anne’s family were tempted by the lure of starting anew. Most of them were eager to go to America. Only one member of the Dudley-Bradstreet party experienced anxiety about the plan: Anne.

Little could she have predicted that her name would make history in this new place that she feared.

A woman of deep faith and sharp wit, Anne Dudley Bradstreet was the first person to publish a book of poems written on American soil.

She is called America’s first poet, though she had to publish her work anonymously, since women were not expected to create such things (in fact, they were considered mentally incapable of it).

Anne was an enigma of a woman for her time. Her father, Thomas Dudley, recognized an unusual cleverness in her. Unlike most Puritan fathers, he took it upon himself to educate his daughter. He encouraged her to devour books and engaged her in conversations involving politics and religion.

He did not realize, at the time, that he was preparing her to write poetry in the future.

There was favoritism for Anne on Thomas’ part: he does not appear to have doted so much on his other children. This might have caused some of the tensions that arose in the family later.

For example, Anne’s sister, Mercy, pledged her loyalty to a female preacher Thomas did not approve of named Anne Hutchinson. Later, Mercy was discovered to have been committing adultery. She was banished from the colony, but her sin left a mark on the family’s name.

Anne, on the other hand, lived devoutly. Puritan children were made aware of their sinfulness as soon as they reached the age of reason. They adhered to the doctrine of predestination, so no Puritan could be certain of salvation.

It appears that Anne took her wickedness very seriously. She never allowed herself to forget that she was a sinner; it caused her to struggle with what we would now call depression.

Anne’s fear of sin made her wary about writing poetry. It would mean going against the norm, and she was a woman!

However, Anne’s father recognized her talent. Thomas Dudley encouraged his daughter to put her words to paper. His approval must have reassured her that she would not sin by writing her verses.

Anne therefore took up her pen, embarking on a new journey: the voyage of writing poetry.

Born on March 8, 1612 in Northampton, England, Anne was the daughter of Thomas Dudley and Dorothy Yorke. She was the second of five siblings. Including Anne, there was one brother and four sisters.

When Anne was a child, Thomas was hired as a steward to the Earl of Lincoln. This gave him a higher status than most Puritans; it also made him wealthier. He was proud of his work, basking in the benefits that came with it.

When Thomas received this position, he moved his family to the Earl’s estate. They enjoyed considerable luxury, as well as a thorough education. Anne was tutored in history, religion, literature, and several languages. An avid reader, she had access to the Earl’s library, which she frequented.

It was at the Earl’s home that Anne met her future husband, Simon Bradstreet. However, when they first met, she was only a girl—so young that it did not seem to raise any eyebrows when she engaged in long conversations with Simon. He was impressed by her astuteness.

Simon Bradstreet had been hired as an assistant to her father. Thomas’ proximity must be another reason why Anne and Simon were able to talk so often: he kept a close eye on them. As Anne matured into a lady and began to change physically, her friendship with Simon transformed into something stronger. He became fascinated by her beauty as well as her mind.

Terrified that these new feelings would cause her to sin, Anne confessed them to her parents. In order to prevent Anne and Simon from engaging in things they would regret, the Dudleys—with the possible exception of Thomas—moved away from the Earl’s house.

However, they kept in touch with Simon through letters; they had all grown fond of him.

Anne would not see Simon again until she was sixteen, at which time she discovered that her feelings had not changed. She was still in love, and so was he. They were given Thomas’ blessing and married quickly. This put to ease Anne’s fears of sin against chastity.

It was a happy marriage, remaining strong through the challenges they would face in the New World. In time, Simon would become the Governor of Massachusetts Bay. This meant he had to leave home often, and his wife grieved his absence.

Anne’s poems about Simon were filled with the longings of a newlywed bride, as we can see in a poem she titled “To my Dear and Loving Husband”—

If ever two were one, then surely we. If ever man were lov’d by wife, then thee. If ever wife was happy in a man, Compare with me, ye women, if you can. I prize thy love more than whole Mines of gold Or all the riches that the East doth hold. My love is such that Rivers cannot quench, Nor ought but love from thee give recompence. Thy love is such I can no way repay. The heavens reward thee manifold, I pray. Then while we live, in love let’s so persever That when we live no more, we may live ever.

In 1630, Anne and Simon were among the most prominent emigrants on the Arbella. They were following her father, who thought this journey the only way for Puritans to practice their religion freely. Simon, who seldom questioned Thomas, joined the family in selling his belongings to pay for the voyage.

Anne remained doubtful about the move. While she went along with the plan like a dutiful daughter and wife, she had no desire to leave England for a little-known territory. Later, she would cite this reluctance as the reason for her inability to bear children. To a Puritan woman, children were signs of God’s favor.

The Arbella left for America on April 8, 1630. It was a part of the Winthrop Fleet, a group of eleven sailing ships and about seven hundred emigrants. The journey was long and grueling. Most of the families had to ration their food. (Wealthier pilgrims, like the Dudleys, had brought resources of their own).

Passengers found the days at sea tedious and uneventful. It was also cold inside of the ship, which caused many to become sick. Combined with a lack of privacy and the noise of their fellow travelers, it’s easy to understand why Anne was unhappy.

The Arbella finally reached her destination of Salem, Massachusetts around June 13, 1630. What the Puritans found waiting for them did not stoke Anne’s enthusiasm.

Visiting a settlement of English people who had arrived before them, they were appalled by the poor quality of the houses. They learned that many early emigrants had died, and the rest were starving. Those who remained were trying to figure out how to survive the unforgiving New England winter when it came back around.

Thomas Dudley agreed with other leaders of the Winthrop Fleet: there was no time to lose. The newcomers began building homes of their own, setting foundations for a new society. It was nothing like the world they’d left behind, and there were few comforts to be found.

Anne could not pretend she liked this, or the fact that wolves could be heard at night howling in the wilderness. Still, she continued to obey decisions made by her father and husband.

Their store of food was inadequate to feed a colony. Even the Dudley-Bradstreet party suffered from poor nutrition. This might’ve been the cause of Anne’s infertility, but she did not see it that way. Instead, she assessed her barrenness from the viewpoint of a Puritan. She considered her infertility a punishment from God, because of her lack of enthusiasm for the journey.

The Puritans established farms and raised livestock, making meals easier to acquire. As their living conditions improved, Anne finally began to have children; however, she struggled with depression for most of her life.

In the New World, paper was a limited resource, reserved for letters and matters of importance. Anne did not have the luxury of spare sheets on which to rework drafts. Instead, she committed her rhymes to memory, repeating them throughout the day. She wrote them down only once certain that they sounded right.

Anne wrote about all sorts of things, ranging from matters of faith to tender verses about her family. She even wrote about her frustration regarding people who called writing a waste of time.

This frustration is strong in the following verses from her poem, “The Prologue”:

I am obnoxious to each carping tongue Who says my hand a needle better fits. A Poet’s Pen all scorn I should thus wrong, For such despite they cast on female wits. If what I do prove well, it won’t advance, They’ll say it’s stol’n, or else it was by chance.

In spite of the doubters, Anne continued to write. In 1650, her work was published as a book in London.

It was given the title The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. To protect her reputation, Anne’s name was not listed as the author; instead, it was attributed to “A Gentlewoman from Those Parts.” This publication was thanks to her brother-in-law, John Woodbridge, who had sailed back to England, taking her words with him.

John hoped the people of England might look with respect at the colonists if they realized fine literature was produced by them. He hoped to settle the lingering tension between the Monarchy and Puritans.

The Tenth Muse would not appear in print in America until 1678, six years after Anne’s death.

The book was a bestseller. It caught the English off-guard; perhaps they envisioned the colonists as primitive, uneducated, and bleak. On the contrary: the colonies were growing, in spite of many challenges. One of these Puritans had produced a volume of poetry that was both impressive and moving.

Like most authors, Anne was never truly satisfied with her work. This is clear in her poem called “The Author to her Book”:

Thou ill-form’d offspring of my feeble brain, Who after birth did’st by my side remain, Till snatcht from thence by friends, less wise than true, Who thee abroad expos’d to public view, Made thee in rags, halting to th’ press to trudge, Where errors were not lessened (all may judge). At thy return my blushing was not small, My rambling brat (in print) should mother call. I cast thee by as one unfit for light, Thy Visage was so irksome in my sight, Yet being mine own, at length affection would Thy blemishes amend, if so I could. I wash’d thy face, but more defects I saw, And rubbing off a spot, still made a flaw. I stretcht thy joints to make thee even feet, Yet still thou run’st more hobbling than is meet. In better dress to trim thee was my mind, But nought save home-spun Cloth, i’ th’ house I find. In this array, ‘mongst Vulgars mayst thou roam. In Critics’ hands, beware thou dost not come, And take thy way where yet thou art not known. If for thy Father askt, say, thou hadst none; And for thy Mother, she alas is poor, Which caus’d her thus to send thee out of door.

Anne continued to live a quiet life after her words became famous. She focused on tending to her children and home. The home, unfortunately, went up in flames when a servant dropped a candle; it inspired a somber poem. It was not long before the Bradstreets built a new one.

She kept out of the way, while the colonies grew around her. They were beginning to form what would one day become a country in its own right, but she could not have known that.

Anne Bradstreet died at the age of sixty on September 16, 1672, in Andover, Massachusetts. The location of her grave is uncertain; in a similar manner, the place where her house stood is up for debate.

What cannot be doubted is that this woman made a contribution, using her words to give the colonies dignity, at a time when women were considered incapable of writing poetry and prose.

The life of America’s first poet proves that, no matter how unforgiving one’s surroundings, there is always room for beauty.

Author’s Note: If you’re enjoying my articles, consider supporting me as a writer by checking out my historical fantasy novels, The Sea Rose and The Sea King. Book one is currently 99c; book two is $3.99. They are both available on KU! ($3.99 can buy a used book as a resource, so I can continue writing articles for you!) Thank you for your time and continued support!

Conclusion: The End of the Alcott Story

In the year of 1868, a red book titled Little Women made its appearance in bookstores. Though marketed as a story for little girls, it was enjoyed by people of all ages. Many were women who had lost husbands, sons, and brothers to the Civil War. The March family’s story healed a nation with its warm messages.

I love this and learned as I read. Definitely improved my schema reading about Anne. Thank you, Mariella.

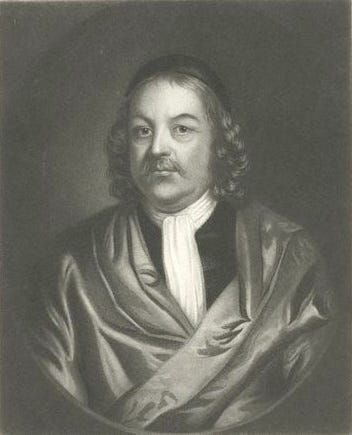

A wonderful tribute to our first poet—too bad there are no portraits of her.