Beatrix Potter: Author and Naturalist, Part II

A fifteen-year-old girl pursuing information about fungi in a male-dominated scientific hub? Scandalous! Yet, she persisted...

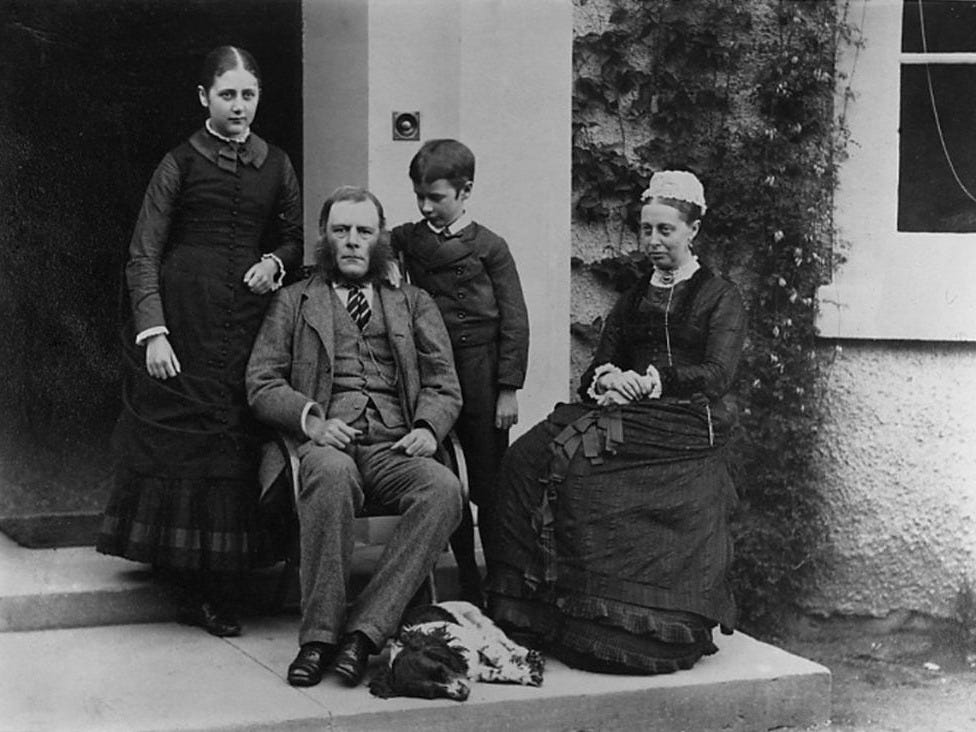

Beloved children’s author Helen Beatrix Potter, whose bunny Benjamin would later be immortalized with the alias of Peter, was not only a creative soul but also determined. Her ventures into the forests surrounding her family’s estates cultivated her fascination for nature. At a young age, she used her artistic skills to draw and color plants and flowers, using her brother Bertram’s microscope to include the minute details.

Note: If you’ve just found this article, take the time to catch up with Part I of this series.

Potter became fascinated by fungi because a lack of information rendered them a mystery. They were not popular topics of study by most botanists at the time. Beatrix could not bear to paint watercolors of specimen without knowing what they were called or how they could be used. Determined that her questions would be answered, she began her first quest.

At the age of fifteen, armed with her sketchbook and will of steel, she set off to Kew Gardens. It was, at the time, a science hub almost completely off-limits to women. She went in with the hopes of speaking to director William Turner Thistleton-Dyer, an expert on tropical plants. He was one of the few who might be able to answer her questions, or grant her access to the resources that could.

Beatrix had an astonishing sense of focus for someone so young. During the autumn and winter of 1895, she spent her free time drawing, virtually glued to Bertram’s microscope as she examined her assortment of fungi. Some of her specimen she collected herself; others were given to her by neighbors and friends who were aware of her fixation.

Linda Lear writes in Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature:

Her objectives had changed from simply assembling a collection of watercolours and photographs to discovering how fungi reproduced. Certain that she could germinate some spores herself, she wanted to study the environment in which they germinated, discover whether or not conditions were the same for each species, what the spawn of each consisted of, and whether or not she could reproduce it more than once. She never articulated a final purpose for her experiments, other than the pleasure of discovery.

Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature, Chapter 5

These are not activities that we often picture fifteen-year-old Beatrix Potter pursuing. They were far from what was encouraged in well-bred ladies at the time. All the same, she delved into research on the topic for no reason other than curiosity.

We underestimate the importance of pursuing subjects for the sake of curiosity alone: curiosity, after all, can trigger inspiration. Inspiration brings with it ideas that could change the course of history. But, I digress.

From her visit with Thistleton-Dyer, Beatrix hoped for access to the Kew Herbarium, among other things. However, in order to meet with the director, she needed to be granted a ticket of recommendation from someone whose name bore weight in the field. Fortunately, she came from a well-connected family.

Beatrix’s ticket was obtained from an uncle, chemist Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe, who had been made Vice Chancellor of the University of London. Though the Potters had strained relationships with most of their family, it appears that Uncle Harry admired his niece’s curiosity. I suspect that, as they bonded through conversation, they discovered themselves to be kindred spirits.

Escorted by her uncle Harry, Beatrix met Thistleton-Dyer at last. She would later write with some amusement in her journal, ‘I think he [Uncle Harry] rather wanted to see Mr. Thistleton-Dyer, but he was most exceeding kind.’ (Source: BP Journal, 19 May 1896, 423-4). Similarly, Thistleton-Dyer probably agreed to the meeting as a courtesy to Sir Roscoe.

According to Beatrix’s journal, Thistleton-Dyer paid polite attention at first. However, when she presented her sketches (which he barely glanced at) and voiced her questions (was he even listening?), his response was unimpressive. Given the attitudes that were common at the time, we must wonder if he might have paid more attention, had Beatrix been a boy.

Did Thistleton-Dyer grant her access to the Kew Herbarium? Was young Beatrix Potter offered any of the resources she’d gone so far to obtain?

In Part III, which goes live next week, we will learn how this interview carried out—and whether Beatrix continued to pursue her fascination with fungi after this quest was through.

Beatrix Potter: Author and Naturalist, Part I

Beatrix Potter. If you do not recognize her name, you’ve probably heard the name of her most famous character, Peter Rabbit.

Okay why does this article has such a low likes count? C’mon people!

So interesting! I had no idea that she was curious about nature