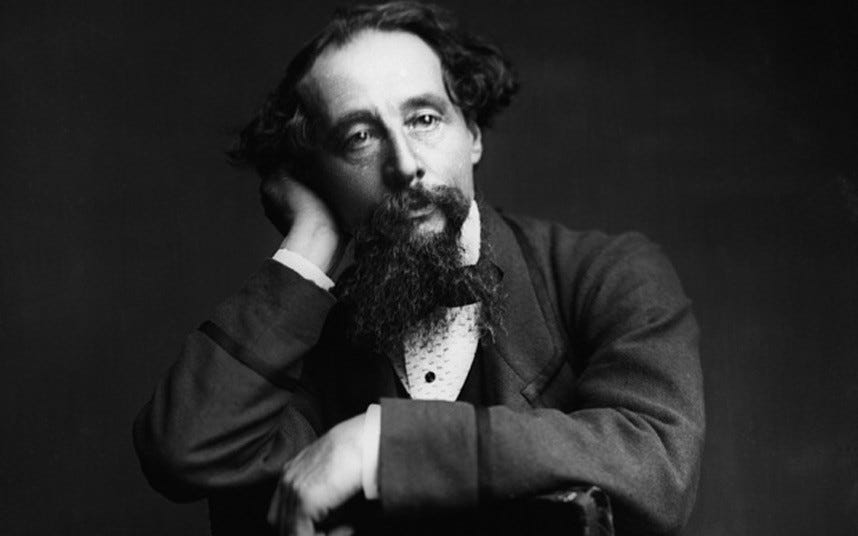

Charles Dickens: The Man who Reinvented Christmas

Dickens’ London—indeed, his life—was a fascinating world of pain, compassion, and contradiction.

“You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

― Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (emphasis mine)

Who but Charles Dickens can write a quote like that and make it immortal?

I’m very excited about our guest at the Tearoom this month. My adventure with Mr. Charles Dickens has a personal note to it.

In 2019, I visited Paris and London with my mom and brother. While in London, I had the fortune of seeing the Charles Dickens Museum on 48 Doughty Street, which was one of his first homes. It was not a planned excursion, but a spontaneous adventure (indeed, we finished our tour an hour before returning to Heathrow Airport).

The previous day, I’d toured the University of Oxford. I was enchanted by the centuries-old buildings, as well as the beautiful green fields we passed on the way there. It was like the movies, with sheep grazing and farmhouses creating a scene of peace.

This peace did not last long, for I became lost in London on our way back from Oxford—without a working phone or money. I returned to the house using dramatic cries for help the force of my own memory.

Several panic attacks later (and with the help of a lady named Catherine who allowed me to use Google Maps on her phone) I got back to the house and passed out in bed. The next morning, I was exhausted.

However, when Mom suggested that we take a taxi to the Charles Dickens Museum, I couldn’t say no.

I had been a fan of Dickens’ work long before I dreamed of visiting Europe. I devoured David Copperfield and The Pickwick Papers, relishing the length of each book.

The concept of a novel written serially, a chapter published every week, fascinated me—because it seemed to lead, by nature, to long books like his. I like long books.

In the years since, I’ve written my own serialized story for the now-defunct Kindle Vella (and am publishing it in parts as the Sea Rose series). It reached two hundred and eighty episodes; I wrote 400,000 words for that story.

I now understand the dedication necessary in order to write such a novel. However, what I wrote was not so coherent as his work. Of course—Mr. Dickens had editors to provide him with feedback, as well as to remind him of storylines which would otherwise vanish into thin air.

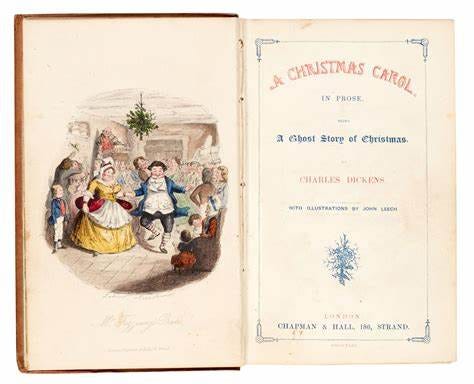

This month, our book club is reading one of Dickens’ shortest but most famous stories: A Christmas Carol. Because December is a busy month, I figured it would unwise to choose something lengthy like Pickwick.

(However, being a fast reader, I’ll finish it quickly. I also plan to read this pairing of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, in the time left over. Anyone who wishes to join me reading these classics by Dumas and Hoffman is welcome.)

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born 7 February, 1812 to John and Elizabeth Dickens. At the time of his birth, the Dickens family lived in a poverty-stricken neighborhood in Portsmouth, Hampshire. He was the second child; an older sister named Frances Elizabeth had been born in 1810.

As their financial situation worsened, the Dickens family increased. In other words, more siblings and not enough money. The boy Charles Dickens, of course, noticed; many of his novels are built around the lives of poor characters, some of them children. These books follow their trials and victories as they do what they can to scrape up a living.

Young Charles dreamed of being rich and famous; however, fortune would not shine upon him yet. He was twelve years old when his father (and the rest of the family, as was custom) was sent to Marshalsea prison, because of unpaid debts. As a result, the boy Charles was put to work in a shoe-blacking factory to bail his family out.

This chapter of his life would prove traumatic. I suspect that he came across cruel overseers as a child; many ‘authority figures’ in his books (such as teachers and parents) give predatory vibes. In Victorian times, children—let alone poor children—were vulnerable to abuse.

We cannot blame Dickens for later avoiding contact with his parents. After Charles reached adulthood, John continued to exploit his son by forging the author’s autograph and selling it. As for Elizabeth Dickens, no one is certain why, but Charles appeared to resent his mother more than his father. (At the end, they were both great annoyances to him).

Eventually, Charles went to school and found a place to live in while he worked for a pittance. It was not a life of comfort, but at least he had the sensation of his life making progress; he was getting somewhere.

In his spare time, Charles wrote stories and submitted them to periodicals. Impressed by the young man’s writing, these periodicals printed his words for their readership to enjoy. Though Charles would not be paid for those publications, he was ecstatic, near the point of joyful tears. To a man who’d had a bleak childhood, seeing his work in print provided the confidence he needed.

Soon he began writing serialized fiction for various papers. His sparkling style and quirky characters, many of whom were relatable to the audience, made him instantly popular. Because they were published in serialized form, Dickens’ tales were long by the time they were released as novels.

His first published novel, The Pickwick Papers, had already been a reader favorite when a serial story; it became a bestseller as a book. The man appeared to possess an endless trove of ideas for stories. He continued to write for periodicals, later publishing these stories as books. Oliver Twist came after The Pickwick Papers; he went on to write Nicholas Nickleby, Barnaby Rudge and The Old Curiosity Shop.

The hit novella, A Christmas Carol, came next, and it placed a new spotlight on the already popular author.

Though Charles had achieved his dream of becoming rich and famous, his romantic life was not so successful. He was a human being and made some very misguided choices, likely due to his troubled childhood.

Charles struggled to forge relationships with women. His daughter, Katey, would later say that her father ‘did not understand how women worked’. After his marriage to Catherine Hogarth in 1836, he soon discovered that he was annoyed by everything she did. Charles wound up doting instead on Catherine’s seventeen-year-old sister, Mary. She lived with them in their Doughty Street home until her early death, probably due to an aneurysm.

After Mary died, Charles grieved as if she had been his wife. He expressed a wish to be buried with her when his time came. This did not come to pass, as one of Mary’s brothers died first, taking that coveted burial plot.

After Mary died, Charles’ affection shifted to Catherine’s other sister, Georgina, who would stay by his side as a friend and housekeeper until his death.

Catherine bore him ten children. None of them lived up to the Dickens name, though we can’t blame them—Charles was a workaholic and an immensely talented creative. Of these children, his favorite is said to have been his daughter, Katey, who was born October 29, 1839. A book has been written about her called Dickens’ Artistic Daughter Katey, which I am excited to read.

She might have been his favorite child because she shared a number of his interests. Like Charles, Katey was involved in the theatre as a young lady, taking part in a number of plays.

I plan to devote a Tearoom post to her in the future; she strikes me as another talented woman forgotten by time.

Learn more about Dickens’ children here.

Dickens’ distaste for his wife Catherine reached such a point that he sent her to a different house, keeping the children for himself.

The saddest part is that Catherine continued to love him; when he died, she donated a lock of his hair and her wedding ring to a museum. Catherine told Katey that she was donating them “so that they will know that he loved me once.”

You must be reading all of this and shaking your head; I certainly did, when I first learned of my favorite author’s personal life.

Dickens was a flawed husband. If he could’ve had Catherine committed to an asylum, he probably would; I’m not sure what prevented it. Perhaps he decided it was not worth the mark on the Dickens name. He was also an uninvolved father, seeming to avoid his children until they reached adulthood.

As with all the other authors I have covered, Dickens wasn’t perfect. His flaws ran deep, originating from a troubled childhood that remains shrouded in secrecy. This is not an excuse for how he treated his wife, but as we embark on this journey, we must keep in mind that he was broken. His vibrant stories and immortal characters were likely crafted as an attempt to muffle haunting memories.

In my next post, I will focus on A Christmas Carol. I will explore how it was received by the public, and the ways in which we continue to celebrate the redemption of Ebenezer Scrooge.

Dickens chose to rekindle the Christmas spirit in a way that some would consider morbid, using ghosts as messengers to warn Scrooge he was making choices leading him dangerously close to a fate like that of poor Bob Marley.

Dickens’ London—Dickens’ life—is a fascinating world of pain, compassion, and contradiction. Thank you for joining me as we embark on a journey with the Ghost of Christmas Past; I hope that we will all learn something new about this remarkable author during the holiday season!

Author’s Note: If you’re enjoying my articles, consider supporting me as a writer by checking out my historical fantasy novels, The Sea Rose and The Sea King. Book one is currently 99c; book two is $3.99. They are both available on KU! ($3.99 can buy a used book as a resource, so I can continue writing articles for you!) Thank you for your time and continued support!

Anne Bradstreet: America’s First Poet

In the centuries since its discovery in the 1400s, America has taken many shapes. It’s brought forth grand ideas and been the scene of countless battles. Such progress did not spring forth overnight.

Great subject this week! Although, gosh, he really wasn't nice to his wife!! I have two sisters and cannot imagine my husband openly preferring them - while I have TEN of his children 😱

Great job!