Read more posts—check out my Table of Contents!

I just finished composing the penultimate draft of this post.

Ever since I read Six Women of Salem by Marilynne K. Roach, I have struggled with the emotional load it left in me.

As I’ve stated in previous posts, when reading about history, I don’t simply read. Some part of me makes a point to grieve for those who suffered, even if it was centuries ago; this means that, while the chaos at Salem is over, the injustice hits me very deeply.

Six Women of Salem is not an easy read for people like me, because it breathes life back into the accused. I did enjoy the book, but I’ve avoided touching it again, putting it off for over a month before I felt detached enough to write a review.

I can only hope that this post does justice to the accused, and that such superstitious nonsense never takes place again.

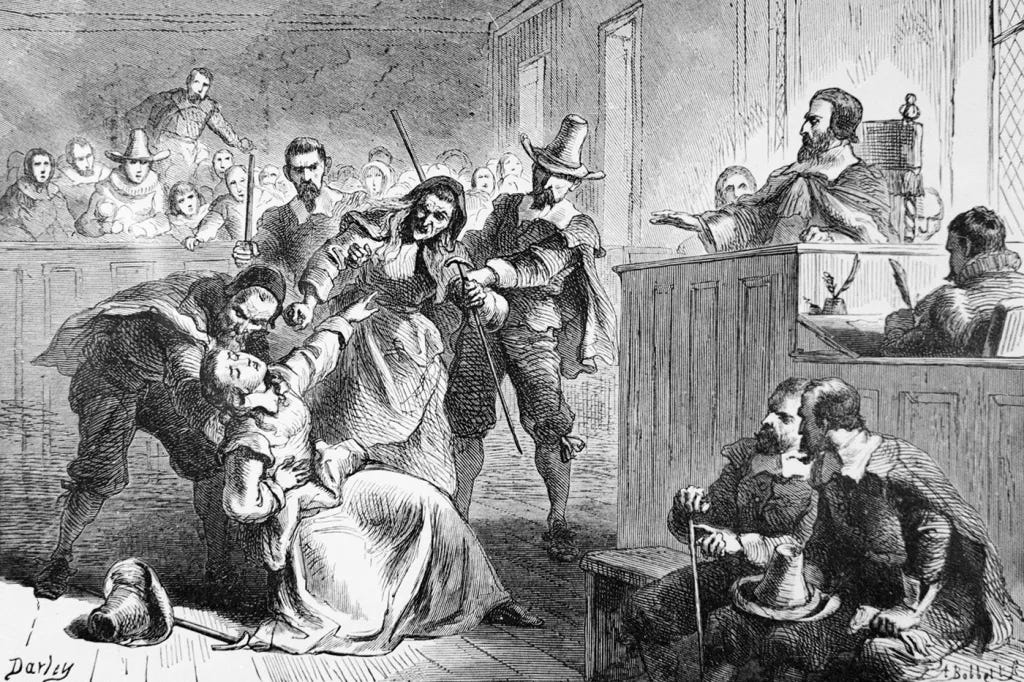

The Salem Witch Trials began in February of 1692. It would drag on until May of the next year. During this time, hundreds of people in the village of Salem were accused of witchcraft; more than thirty were executed.

It only somewhat makes sense when I put it in the context of the time. I struggle, all the same, to imagine a society where some hysterical little girls could cause such harm to a community.

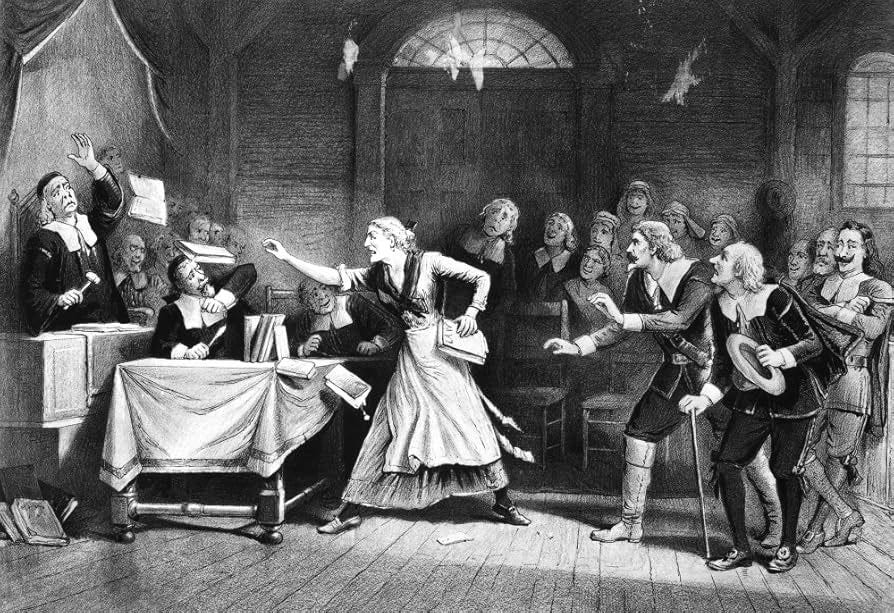

Marilynne K. Roach painted an intimate, detailed portrait of these events. She made the Salem Witch Trials into more than some obscure event we only hear about during Halloween.

She told the story in such a manner that it became personal to me, and I grieved so much by the end of it that I wasn’t able to think about it for weeks.

Writhing and Convulsing

This book explores that dark chapter of our history by following six of the women tangled up in it.

The women were from different backgrounds and, under regular circumstances, would not have spent time in the same room. They were forced to share a dingy prison cell for weeks, months, by the judgment of superstitious neighbors.

These women were Rebecca Nurse, Bridget Bishop, Mary English, Ann Putnam Sr., Mary Warren, and a slave woman named Tituba. The first part of Roach’s book presents thoughtful introductions for each woman. She spins believable stories using scant surviving information.

The fact that Roach makes them so human is why I struggled to write this. Rather than listing distant facts, she allows readers to feel what the accused felt. We experience their terror when neighbors point fingers at them. We know the panic they felt as they wondered if their families would also be threatened by such accusations.

Scenes describing the trials were irritating. Whenever one of the accused stepped before the magistrate, Mary Warren and the other ‘afflicted’ writhed and convulsed every time. Writhed and convulsed. The words writhed and convulsed were repeated enough that they no longer had a dramatic effect on me. No, I wanted only to knock sense into these people.

Worse, though, were the magistrates willing to take these reactions as proof of witchcraft.

How can it be that so many people were accused, people who had been known and respected? All of the evidence against them consisted in writhing and convulsing! Why did so few people call out the folly that any rational human can spot, especially when it happened so often?

The Name of Tituba

Tituba, the slave woman, was given a thoughtful introduction. I appreciated the effort Roach made in giving her an identity beyond what folklore paints of her.

Being at a disadvantage due to her rank, Tituba was clever in how she approached the situation. Rather than denying witchcraft allegations, she bought time by saying that she had cooperated with the devil but repented. She swore she had completely renounced that path.

While this strategy saved her from the gallows, Tituba remained in prison after the trials ended. She was certainly out of a job with her employers, the Parris family. Furthermore, no one else wanted to pay bail for a slave who had earned herself such a reputation.

Tituba does seem to have gotten out of prison, but no one knows who bought her freedom or why. She vanished into history, as if she had never existed.

The origin of Tituba’s name remains a subject of speculation. Roach suggests she might have been a native from a village near the Amacura river, in what is now Venezuela.

It’s speculated that she was among several natives captured by Captain Peter Wroth of the British ship Savoy. The Savoy is known to have pillaged land around Amacura on August 2, 1674, and later made a stop in Boston to ‘sell goods’.

Roach writes:

His excuse was that, with England at war with Holland, the women were probably Arawak allies of the Dutch—unlike the large groups of men they had traded with downstream, whom they assumed were Carib allies of the British (as well as better able to resist capture).

She also presents theories about Tituba’s name:

Spelling in the seventeenth century was still not standardized, so it depended on the creativity of the writers and how they heard a word. “Tituba” is the way that Samuel Parris, who most controlled her life, spelled her name. (Of course, he, like others, also used the alternate spelling of Putman for Putnam.) Boston jailer John Arnold used the spelling “Tituba” in his bills; Robert Calef and John Hale did likewise in their later narratives, as did Magistrate John Hathorne in his notes of court proceedings, though not consistently. Other variants include Tetaby, Titibe, Tittabe, Tittube, Tittapa, Titiba, Tittuba, and Titaba.

Shattering Flashbacks

The Salem Witch Trials are a reminder of how cruel humans can be to one another.

Not only did these accusations cause unnecessary death, but the ‘neighbors’ didn’t even—in their so-called Christianity—show compassion for the accused.

As a Christian myself, I was deeply troubled after reading one of Roach’s excellent, gut-wrenching flashbacks. In this flashback, we live the moment when elderly Rebecca Nurse was excommunicated from the church she’d loved all her life:

[Reverend] Noyes lists detail after detail, with only the occasional phrase making its way to her hearing.

“For these and many other foul and sinful transgressions … cast you out and out you off from the enjoyment of all those blessed privileges and ordinances ... that you may learn better to prize them by the want of them.”

Rebecca’s legs ache from standing. … No, she thinks. I at least tried to follow God’s councils.

“As an unclean beast and unfit for the society of God’s people... pronounce you an excommunicated person from God and His People.” At last he finishes talking, and one of the elders steps forward.

She catches some of his words: “... depart the congregation as one deprived worthily of all the holy things of God.”

A faithful, elderly woman who had lived her life believing in God and His mercy, was cast away from His favor before she went to the gallows.

I could not sleep for days after I read that.

This same Reverend Noyes apparently refused to pray with John Procter, with hours to go before the man’s hanging:

Because Procter would not confess to what was so obvious, what the court had proven, how could he presume to be able to put his soul to rights under those circumstances?

Procter objected. At least pray with him now, he asked.

But Noyes refused, unwilling to waste compassion on the obviously guilty—what was the point?

Some pastor that was.

I nearly wept when reading Martha Carrier’s farewell to her children:

Martha Carrier made her farewells to her children. But the youngest of them at least, their shrill voices verging on tears and then dissolving into weeping, begged their mother to confess, to choose life and stay with them. One of them lamented that their own mother had dedicated them to the Devil, but the mother’s impatient harried tones interrupted all of this. Words were hardly distinguishable, the emotions too raw to miss.

Mercy for the Accusers

This book was intended to give the accused faces and emotions beyond those we hear about each October. It fulfills this mission devastatingly. I felt as if my own family members were being led to their deaths.

I shared in their hopelessness, felt endless hours in a freezing jail cell. I sensed also their frustration when, at every trial, Mary Warren or Annie Putnam or Mercy Lewis continued to writhe and convulse.

It was such a tragic lack of regard for human dignity, a prank allowed to go on for too long.

Usually, I try to find compassion for the people who are wrong. In the case of these accusers, I struggle to do so. I’ve tried; for the life of me, I cannot wrap my mind around why they continued with this ruse for months.

Did they enjoy the sense of having power? Mary Warren was a servant girl for the Procters. Were her accusing words an attempt at retribution for a wrong done to her?

Annie Putnam was a little child; it’s possible that, being young and impressionable, she was manipulated by her mother. Anne Putnam, Sr., did seem to have an inflated sense of her importance in the neighborhood.

So, can any of these things bring about compassion for the accusers? In Annie’s case, maybe.

By the end of the book, the only recorded instance of repentance was in the case of Annie Putnam. Once she grew up and was able to reason, it dawned on her that she had been used by her family to condemn people to death.

Having hidden herself away for most of her adolescence, Annie made a public appearance when she reached womanhood. By that time, the rest of her family seems to have died.

Annie petitioned the village church for permission to be baptized (there are baptism records to prove it). After some debate, her repentance was accepted as genuine. She confessed her grievances and joined the congregation.

Annie had the good sense to recognize that, though she was not using her free will, she had been utilized in something evil. The other accusers seem to have faded into history. Mary Warren vanished into thin air—like the ‘evidence’ for her accusations.

Annie did not live long after her baptism. She succumbed to illness and was buried with the rest of her family. The Putnam grave mound has long since disappeared. However, traces of this tragedy continue to fill the air—like ghosts, some might say.

I was glad to put Six Women of Salem back on my shelf after writing this review. It contains masterful storytelling, and it is a book that will haunt me for a long time. It does what should have been done a long time ago, making the accused into more than names on a memorial site. These men and women were human.

History is not always enjoyable. Much of it is ugly, surreal, and shameful.

Let us not turn our backs, even to dark history; instead, I pray that we all learn from these events, lest they take place again.

John Adams, the Second President

I began a personal project last year. The books we read in school don’t usually go into detail about presidents and their lives. This is tragic, because many of the decisions that shaped our country, for better or worse, were made by presidents grappling with issues unique to their times.

This is very beautifully written! There is nothing quite like putting names and realistic stories to the tragedy. Thanks for sharing even though it was hard to write!

I too have a fascination for this moment in time – when an entire community went collectively mad, and took it out on women. I will check this book out. Favorites of mine are Stacy Schiff’s The Witches and the novel, The Heretic, which is told from the point of view of Martha Carrier’s daughter.