Lizzie Siddal: The Tragic Life and Death of Art’s First Supermodel

Lizzie Siddal. Perhaps you do not know her by name, but you’ll have seen her in John Everett Millais’ famous rendition of ‘Ophelia.’

Even those who are not well-versed in art are bound to have seen paintings by members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Founded in 1848, it included painters such as William Holman Hunt and Thomas Woolner. Later, their company would be joined by more famous names, such as John William Waterhouse.

I am not alone, I’m sure, in naming the Pre-Raphaelite works among my favorites. Their colors, stories, and attention to detail are surreal. These paintings also owe much of their splendor to the models who sat for them, women who were captured into every piece.

We never talk about these ladies who were hired to sit and pose as goddesses. I’d like to change that. Let’s begin with Lizzie Siddal. Perhaps you do not know her by name, but you’ll have seen her in John Everett Millais’ Ophelia.

Not having read Hamlet, I first looked at the painting and saw a beautiful woman lying in water, her expression one of shock. How did I come to be here? she appears to ask, too stunned to prop herself up. Where do I go next? A Google search informed me of the play’s character, Ophelia. It changed my impression, adding a darker layer to the painting.

In the play, Ophelia drowns; this is her final gasp before she plunges, her last glimpse of sky before she steps off-stage.

Lizzie’s face is featured in so many pieces that I found myself wondering about the woman behind the brush-stroke. She became a sought-after model for many painters who, at the time, were all the rage. There must have been something special about her!

Who was Lizzie Siddal, the woman who modeled for Millais’ Ophelia, echoing her despair so well? Where did she come from, and how did her work as a model for painters affect her life?

To my delight, I discovered a book called The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood by Jan Marsh. It sheds light not only on Lizzie, but on other models whose beauty marked this special time in art history. The other models mentioned are Emma Brown, Annie Miller, Fannie Cornforth, Jane Morris and Georgiana Burne-Jones. I plan to do research on all of them, sharing their stories as I go along.

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall was born on 25 July, 1829. She would later change the spelling of her surname to Siddal.

Born to an ordinary, working family, her beauty would make her famous in the art world. Once she was discovered by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, her face graced painting after painting as the movement gained popularity.

Her father, Charles Crooke Siddall, was a cutler—he owned a knife-making business. Her mother, Elizabeth Eleanor Evans, was of Welsh descent. Eleanor was their third child. Her earliest years were spent with her parents and two older siblings at a house in Holborn, London. Eventually, they would move to Southwark in south London, where five more siblings would be born.

How does a cutler’s daughter wind up chosen by a group of high-profile painters? It was the sort of happenstance that many of us would envy. Accounts do vary about the circumstances of this luck. The only consistent fact is that, at the time, Lizzie was working at a Cranbourne Alley milliner’s shop. The year is also agreed upon: 1849.

One version claims that, while at the milliner’s, she made the acquaintanceship of a Pre-Raphaelite painter named Walter Deverell. He was accompanying his mother to the shop when he spotted Siddal at the back. Struck by her fair complexion and the color of her hair, he invited her to model for them.

Another version claims that it was William Allingham, another painter, who found her. He’d gone to the millinery to meet a woman on a romantic liaison. Lizzie was busy with her chores when she caught his artist’s eye. Enthralled by her appearance, Allingham suggested her as a model for Deverell, who was working on a large oil painting inspired by Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

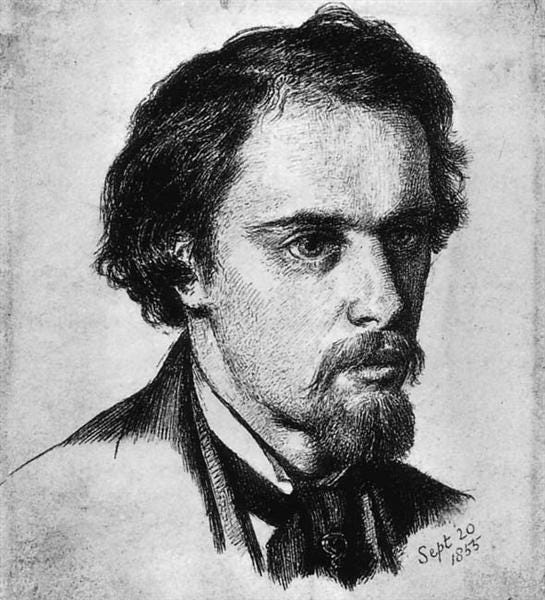

Siddal’s beauty enthralled all of the painters, but it was artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti who fell hardest. He was another one of the Brotherhood’s founders. Obsessed with her beauty, he was more persistent with his pursuits.

Lizzie Siddal and Gabriel Rossetti married after a ten-year cycle of courtship and separation. It was a troubled marriage; by that time Lizzie was worn out, trapped by the labels accompanying her role as model. Furthermore, Lizzie and Rossetti were both temperamental, which can bring disastrous consequences under pressure.

Women who worked as models were written off as having loose morals. This was the public’s opinion about Lizzie in spite of the fact that, due to their landlord’s conditions, the Brotherhood never painted nude women. Her beauty and fame did not save her from slander to her character. This slander caused Lizzie to sink into a profound depression.

Her face was known by every art admirer in England, but at what cost? She found herself fighting a battle she couldn’t win—a battle for dignity—which led to an addiction to opium.

When Lizzie attempted a venture of her own into the world of art, Rossetti was glad to teach her. At the same time, he placed her on a pedestal, implying that she was only to be admired from afar. After their marriage, Lizzie posed only for him, turning down other painters when they asked her to model for them. One must wonder whether this was done of her own volition, or if he forbade her from sitting for them.

Dante’s sister, Christina Rossetti, alludes to his near-obsession with Lizzie in her poem, In An Artist’s Studio:

One face looks out from all his canvasses, One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans; We found her hidden just behind those screens, That mirror gave back all her loveliness. A queen in opal or in ruby dress, A nameless girl in freshest summer greens, A saint, an angel; – every canvass means The same one meaning, neither more nor less. He feeds upon her face by day and night, And she with true kind eyes looks back on him Fair as the moon and joyful as the light: Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim; Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright; Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Their marriage was fated to last only two years. Her addiction to laudanum was stronger than even her husband’s worship of her. After she birthed a stillborn baby, her agony became far worse.

Author Lucinda Hawksley describes Lizzie’s emotional state after this loss in her book Lizzie Siddal: The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel—

She would sit in the drawing room for hours without moving her position, just staring silently into the fire. (…) Once she refused to eat and became increasingly emaciated. The nurse hired as a maternity carer was living with them and taking care of her, but Lizzie was too wrapped up in grief to be aware of anything except her loss. When Ned [Burn-Jones] and a heavily pregnant Georgie [Burne-Jones] came to visit her, Lizzie was in her room alone, staring at the empty baby’s cradle, which she would rock tenderly from side to side as though soothing her daughter to sleep. As the door creaked open she looked up and told them to be quiet so as not to wake the baby.

Lizzie soon became pregnant again, but her mind remained troubled, carrying the burden of grieving her first child (in addition with the other battles she was fighting).

Tragically, Lizzie was not destined to win these battles. On February 10, 1862, Rossetti returned from a meeting with his colleagues to find her in a laudanum-induced coma. Frantic, he summoned a doctor. However, she was too far gone for any physician at that time to be able to save her.

Lizzie Siddal Rossetti passed away in the early hours of February 11, 1862.

Rossetti attempted to honor Lizzie with one final act: he placed a manuscript of his sonnets in her casket to be buried with her. Six years later, he regretted this choice and asked for her body to be exhumed. Reclaiming his sonnets, he published them under the title The House of Life.

What can we think of Dante’s impulse to bury his work with Lizzie? Was his mind so clouded by grief? Was it a wise decision to reclaim his gift from her cold, lifeless body? I can only imagine the moment when the casket was opened and he reached for his work. What else did he see?

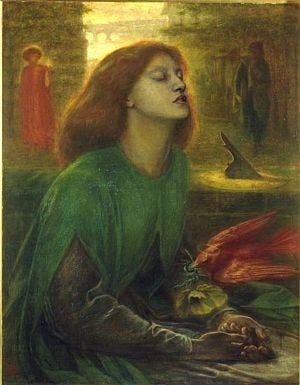

In 1870, Rossetti ‘revived’ Lizzie with a stunning oil painting called Beata Beatrix. It depicts a dove descending from heaven, placing in her hand a poppy flower. Opium is derived from poppies; the significance is not lost here. The painting is a sad tribute to their short-lived but passionate marriage.

Rossetti’s life did not become easier with time; plagued with health problems and struggling with depression, he at one point tried to commit suicide with opium, as Lizzie had done. In his 1892 Autobiographical Notes, fellow artist William Bell Scott recorded that, during a visit to Scotland, Rossetti was gripped with an irrational fear of a chaffinch. He claimed it was his dead wife watching him in spirit form.

What is it that sets apart the models of Pre-Raphaelite art?

According to The Pre-Raphelite Sisterhood, the models most commonly feature “large, lustrous eyes (…) surrounded by a mass of loose hair, looking soulfully out of the canvas. Neither sad nor cheerful, but somehow charged with an intense, internal passion, [this] face has a brooding, haunting quality that engages attention but remains distant, remote, impersonal.”

Lizzie Siddal possessed these features and became a supermodel. However, she grew tired of being ‘distant, remote, and impersonal.’ Her choice to become an artist feels like an attempt to separate herself from ‘the model discovered in a millinery.’ It is not known whether she always harbored interest in painting; all the same, she picked a path and attempted to follow it.

Her husband guided her in the practice of painting, but it was not enough to ease her pain. In spite of this new pursuit, Lizzie’s internal struggle continued.

Her fame cost her dearly, stealing from her any form of inner peace.

I would like to share one of her paintings.

Look at this self-portrait she painted in oils. Take the time to gaze at her face without seeing Ophelia. What does Lizzie want you to know about herself? What is she saying with this bold rendition of her face, with eyes that pierce the soul? Are those eyes the same that Rossetti hallucinated when he was afraid of the chaffinch?

Click for more of Lizzie Siddal’s art!

In 2019, a lock of Lizzie Siddal’s hair was put on display at the “Pre-Raphaelite Sisters” exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in London. It had been discovered by a collector, tucked away in an envelope on which Rossetti had written Lizzie’s Hair. He must have clipped a lock of it for safekeeping before she was buried. For the full story, read this fascinating article.

Can we call this closure for Lizzie, that she should reemerge so many years after death—even if only as a lock of hair?

You decide; just look at the hair and see how beautiful it is!

Author’s Note: If you’re enjoying my articles, consider supporting me as a writer by checking out my historical fantasy novels, The Sea Rose and The Sea King. Book one is currently 99c; book two is $3.99. They are both available on KU! ($3.99 can buy a used book as a resource, so I can continue writing articles for you!) Thank you for your time and continued support!

Louisa May Alcott: What Were Her Sisters Like?

It’s the second Friday of November! I hope you’re enjoying Little Women; I am currently on Chapter 12, and the story is having the exact effect on me that I expected: it’s like a warm blanket on a chilly winter’s night. It is familiar and gentle, filled with messages of forgiveness and love.

What an extraordinary homage. Her self portrait is so very poignant, the poem you uncovered about her so very poignant, and your essay built so beautifully around your research. Way to go.

Really enjoyable essay...I'm so glad you posted in Notes or would've missed it! Did you know Elizabeth Siddal was also a poet (see My Ladys Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal)? Also...if you don't mind gratuitous nudity and general absurdity, there is a very informative BBC miniseries (2009) about the Brotherhood which dramatizes rather accurately (I think), Siddal and Rossetti's relationship--it's called, Desperate Romantics and stars Aiden Turner as Rossetti. Have you seen it?