Louisa May Alcott & the Struggling Roots of Little Women

Louisa’s mother—caught in a spell of depression—confessed that she imagined Louisa would one day provide for their family. These words planted a dream in the child’s heart.

“It’s so dreadful to be poor,” sighed Meg, looking down at her old dress.

—Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

When I think of the novel Little Women, my mind settles on that line spoken by Meg, one of the four March sisters. It is almost an echo of a diary entry that Louisa May Alcott wrote when she was fourteen, after another of her father’s attempts to make a name for himself failed, leaving him unemployed:

“I don’t see who is to clothe and feed us, when we are so poor now,” Louisa confided to her diary. … She knew by now that Bronson Alcott would not rescue them. That the usual Alcott meal was a piece of bread, an apple, and water, with frequent stretches of only bread and water, did not seem to bother him.

— Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women by Harriet Reisen (emphasis mine)

Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy have accompanied many wide-eyed children as they learned to love books, particularly girls. It’s a treat to follow their adventures, which are sometimes joyous and sometimes heartbreaking.

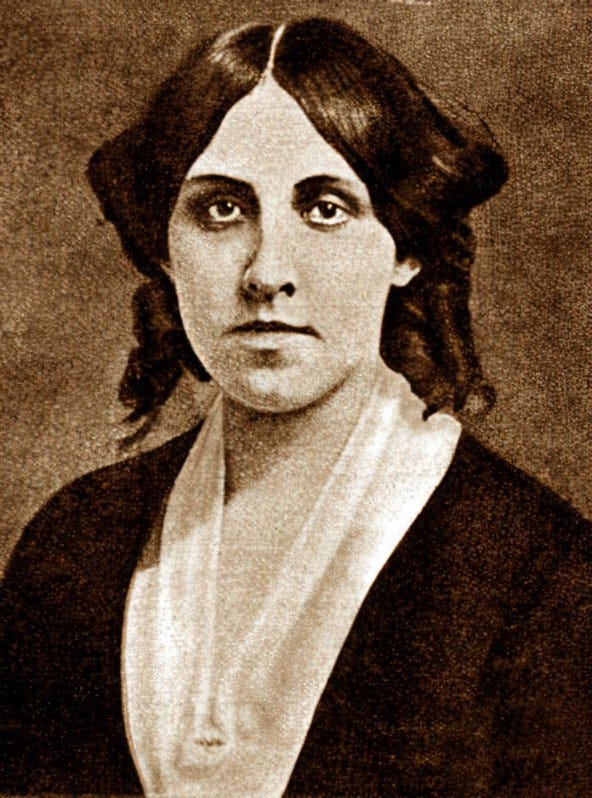

The author of these four sisters, Louisa May Alcott, is present in each word spoken by the characters. It’s known that Jo, in particular, is based on Louisa herself; Jo’s personality was inspired by Louisa’s own as she was growing up.

Little Women’s first scene is steeped in longing and grief. Christmas is coming, and their father has gone off to war, meaning that the girls and their mother, affectionately called Marmee, are struggling through Advent. They must be grateful for each other’s company, soldiering through a cold winter with no presents or Father.

I found myself drawing a similar parallel when Meg went on to speak the following words:

“Don’t you wish we had the money Papa lost when we were little, Jo? Dear me! How happy and good we’d be, if we had no worries!”

These words do not mean much to someone who hasn’t picked up a biography of Louisa May Alcott. I’ve finished one, and am halfway through another. While Jo is the character designed to be most like young Louisa, it is Meg in this chapter whose words might have come from young Louisa’s mouth.

Louisa May Alcott grew up in poverty. The blame for this falls on her father’s shoulders. He lived his life pursuing a belief that is nice in theory but should not be practiced when one has a family depending on you.

Like Percy Shelley, Bronson Alcott steeped himself in ideas that were new and peculiar at the time. Bronson’s fixation was on Transcendentalism; he plunged in head-first, pulling his family along with him—creating a childhood that would damage the strongest of little girls.

Louisa May Alcott was born to Bronson and Abby May Alcott on November 29, 1832. She was the second of four children; as we read Little Women, we will see parallels between the author and many characters into whom she poured life.

She was, from the start, a child with a temper that only her mother could control. Bronson kept notes on her behavior when she was a baby; her episodes continued well into her teen years, though I don’t know if he continued to write about them when she was fourteen.

In essence, Bronson described Baby Louisa as being a wicked child, prone to trouble and slow to feeling remorse for her antics. Perhaps he was being unfair; to put it mildly, his own choices were questionable.

He painted the portrait of Louisa being a storm that could not be tamed. He wrote that she would hurt her older sister, Anna, for fun. In comparison, Anna was described as good and gentle in spirit (perhaps the case is that she endured his discipline without complaining; patient he was not!)

When he attempted to scold Louisa, she would dissolve into tears and claim he did not love her. Indeed, it seems she bonded most with her mother, Abby; though she loved her father, he does not seem to have been a good choice as a confidante.

While Bronson Alcott was not the only person practicing Transcendentalism at that time, he was one of its most vocal followers. He even started a magazine called Dial, directed to followers of that philosophy, where his words were printed to bemuse or enthrall anyone who might come across them.

Transcendentalism emphasizes the spiritual and intuitive over the material and empirical. Bronson’s choices are an example that, when practiced in a fanatical way, it can be a difficult lifestyle to sustain. Perhaps it is feasible to do so when living alone, but not when raising a family!

Alcott dedicated himself to this cause, attempting to win disciples for his way of thinking. Do not misunderstand: it isn’t wrong to have a set of beliefs you cling to. However, Bronson seemed to forget he had young children with basic needs. He was unconcerned about their comfort, nor did he care to provide them with a safe place in which to grow.

In the middle of this was his wife. While Abby agreed with his beliefs to a degree, her journal entries betray frustration. She followed Bronson each time he decided to move, attempting to be a supportive wife. However, even if she did believe in some of the same things, seeing her children hungry and neglected must have been a wake-up call.

I cannot help but draw a comparison here.

Percy Shelley, in his choice to live a nomadic life, did not provide a safe place for his children. Both he and Bronson expected the mothers of their children to see to their needs; meanwhile, they went off in pursuit of some great other, built castles in the air, indulging in hobbies, avoiding responsibility.

While Bronson Alcott preached a form of equality, can we call it equality when the brunt of childrearing and providing food fell on his wife?

Louisa’s father sneered at the idea of working for money. He constantly borrowed from friends and relations, relocating when landlords realized he could not pay the rent. This left Abby with no choice but to ask her family for money. She did so often enough that even her brother Sam, who was her dearest sibling, finally refused.

“If we have to work,” was Sam’s response, in reference to her husband, “why shouldn’t he?”

Did Bronson know of Sam’s words? If so, they did not sway him to take a responsible path. He continued with his dream of building a Transcendentalist utopia, dragging his children and frail wife along for the ride.

Abby was constantly pregnant—and had many miscarriages, after which she required weeks of recovery. Having lost relatives to childbirth, she was terrified of meeting the same fate every time she found herself to be expecting.

During Abigail’s periods of convalescence, her children were sent to stay with relatives. One time, Louisa was sent with her grandfather, but her personality proved to be too much for him. The next time Abigail miscarried, he did not offer to take Louisa; she was sent instead with some family friends.

My heart hurt for Louisa as I read these things. A childhood laden with poverty, instability, and rejection would have created painful wounds.

By the time she reached adulthood, Louisa struggled with depression. Indeed, Louisa has a haunted look in her eye, in a portrait taken of her when she was twenty. She did not have the childhood she deserved, yet wrote stories for children all the same…stories about happy families.

In time, two more sisters arrived: Elizabeth in 1835 and Abigail May in 1840. Bronson’s behavior remained unchanged when there came new mouths to feed.

By vocation, he was a teacher, but his unorthodox ways of educating meant that no school wished to keep him for long. He was unafraid of speaking about topics that were inappropriate for children; parents complained. When he could not find work at a school, he attempted to start one of his own.

The experimental Temple School was popular, for a while, among Transcendentalist families. Bronson taught in a brightly lit room in the Masonic temple, where he would take both girls and boys as pupils, using figures of speech that were…creative, to put it lightly.

In time, his ideology became so extreme that even Transcendentalists were uncomfortable. He was tolerated, though, in part due to his connections (such as Peabody, Thoreau and Emerson).

Bronson was an abolitionist and believed in racial equality. It was not until he admitted a little girl of color into his classroom that his job as a teacher went up in flames. Parents of the white students did not want her to be included; they demanded that he remove her from the class.

When he refused, all of the parents pulled their children out; he found himself unemployed once more.

Noble as Bronson Alcott’s gesture might have been in the name of equality, he was now homeless with a great deal of debt. To make matters worse, Abigail’s health faltered, as well as her spirits after each miscarriage.

Louisa watched all of this with attentive eyes.

One day, her mother—apparently caught in a spell of depression—confessed that she imagined Louisa would one day be the one to provide for their family. Those words, spoken in the mires of despair, placed expectations on a little girl who scarcely had a toy to her name.

Some might call it unfair; however, those words planted a dream in young Louisa’s heart. The problematic second child of Bronson Alcott, the one he practically called wicked in his journals, would go on to do great things.

In 1842, an opportunity surfaced for Bronson that revealed the frailness of the Alcott family’s bond. He was invited by Ralph Waldo Emerson to visit Transcendentalist schools in England, all expenses paid.

He hemmed and hawed for a bit before accepting. It’s telling that Abby packed his bags for him. She did not seem all that sorry that her husband would be gone for several weeks.

Later, she would write:

I am summoning all the important and agreeable reasons for his absence, and among the most worthy is the belief that these Trans-Atlantic worthies will be more to him, in this period of doubt, than anything or anybody can be to him here.

Did he care so little for his wife and children? Abigail seemed to believe it, and she would enjoy the days of respite from her husband and his choices. Though she agreed with much of what Bronson preached, such as racial equality, even belief can become strained when it puts one’s survival in peril.

These many trials made a deep impact on Louisa’s young mind. We can see scars left by her childhood in how passionately she worked to make a name for herself.

Abby’s words to Louisa about being the provider would surface again when she was sixteen. They were leaving Concord for Boston, where Abby (not Bronson) had asked some friends to help her find work in order to support their children.

Among the last things Louisa wrote in Concord that year, we find a resolution:

“…I said defiantly, as I shook my fist at a fate embodied in a crow cawing dismally on the fence nearby,—

‘I will do something, by and by. Don’t care what, teach, sew, act, write, anything to help the family; and I’ll be rich and famous and happy before I die, see if I won’t!’”

I think that we can all agree, this is what she did.

She became a celebrity with her books, but that’s not all Louisa May Alcott achieved. From volunteering as a nurse during the Civil War, to adopting her orphaned niece, she dedicated her life to doing good things for the world. Like her father, she envisioned a place that was different, happier and fairer; unlike her father, she was willing to work for it.

As November begins and I crack open my copy of Little Women, I will think of its author with new respect and pay greater attention to her words.

If you would like to join the Teacups and Tomes classic novel read-along, click here and request to join the group. We’ll be having discussions there, and an overall jolly time!

I look forward to learning more about Louisa and disappearing into one of the tenderest, most nostalgic novels that exist today.

November will be a cozy month, indeed!

The Mother of the Brontës: When Maria Met Patrick

Maria Branwell’s legacy has come to be her daughters. The wise and fierce words of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë burn in the world as brightly today as when they were written.

I have always been fascinated by the transcendentalist movement and, somehow, forgot to remember that this author was connected to it through her father. I really appreciate your research! As a parent of two little boys now, I can attest that the life he was seeking was not in alignment with a family(even more at those times). There have been moments since becoming a mother that I have had to grieve the fact that my days are not entirely my own anymore and that what used to be worthwhile pursuits of aimless thought or reflection have been dethroned for the ordinary moments of home life now. I am not even truly resentful or upset about it, only remembering the sadness when my mind caught up to the reality that children's needs sometimes come at the expense of what I would desire to do. Long ago are the days of spending hours reading or learning on a topic only to find myself neglecting basic needs like hunger. I empathize for Alcott's father but at the same time believe that he undervalued his role as father and provider. Children that are brought to this world really do humble(or at least I hope) the adults in their lives, at least for a while, into putting dreams and certain aspirations on a shelf to pick up another time or accept their lack of viability.

Interesting to read this as I'm in the middle of re-reading LITTLE WOMEN. It seems to me a good argument against the tendency of contemporary filmmakers who adapt the book to insist that the Marches *are* the Alcotts 100%—Bronson Alcott really does not sound at all like the Mr. March of the novel. (Although it might very well account for Mr. March being a slightly vague, not really three-dimensional character compared to others in the novel if he was far less drawn from life than the characters of the mother and sisters.)