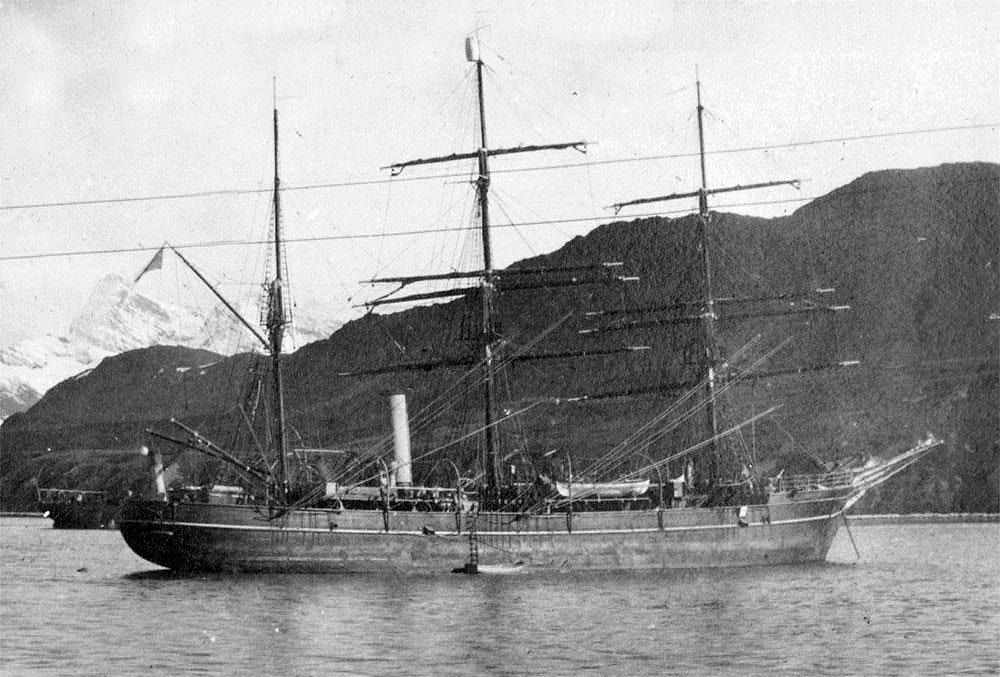

Shackleton’s Endurance: A Tale of Survival

The crew of the Endurance survived polar conditions, thanks to the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

There is something ageless about books that recount adventures.

In 2025, it’s easy to feel as if the world has been explored, as if there’s nothing else new to find. This is not true; mysteries remain, even if they’re not as dramatic.

There might be few giant mountains left to name, but we still search for cures to illnesses. The bottom of the ocean remains largely undiscovered. And, of course, there’s space exploration.

Human nature is transfixed by tales of perilous journeys. Some of the best-known tales are of sailors. These men (and women!) braved wild oceans; some of their ships never returned.

They might have been discovered at the bottom of the sea. In many cases, they were only brought to life in lore as ghost ships.

The crew of the Endurance became stranded in Antarctica in 1915. They avoided death because of the leadership skills of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure was written by a member of this crew, F.A. Worsley. He was the captain of the Endurance, but even as captain, he trusted Shackleton’s instincts to get the men to safety.

The ship would not survive; it met a tragic end at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, where it was frozen in an icy tomb.

Recently, the Endurance was discovered, using advanced technology. While this is great, I think a more thrilling story is that which Worsley tells.

Not one man from the crew died. Shackleton was determined to get them home alive. He was willing to suffer all forms of discomfort in the process.

It is a matter of history, Worsley wrote, that Shackleton never did lose a man from his crew. But his caution was a product of an altogether exceptional brain:

...unlike some explorers he put the safety of his men far above any achievement that might be possible to him. I have never known anybody so careful. I think that somewhere else in this book I have said that he did the most dangerous things but did them in the safest way, and I repeat it because I think that it describes Shackleton more accurately than a volume of words.

Worsley’s book is a testament to Shackleton’s leadership. It begins at the grim moment when Shackleton told the crew to abandon ship, sensing that the elements would overpower the Endurance.

It’s also an ode to the spirit of the time: The Great War was raging at home, and sailors were planning to enlist when they returned. None of them seemed to think of kicking up their heels before a hearth.

I sensed in these men a resolve that feels alien today.

Worsley and many other sailors would, indeed, enlist. A chapter is dedicated to recounting his adventures as a sailor during the war. It seems that these sailors were made of different stuff than we know; many posts could be dedicated to them.

However, this post is about the Endurance and Shackleton. It is about a form of adventure that few of us would imagine today.

Photos and videos exist of this dramatic event:

The last work done by our cinematographer, Frank Hurley, before his valuable camera was…thrown away, was to film the masts of the Endurance as these were slowly twisted from her by the overpowering ice-floes. It took extreme care and patience and wonderful judgment to enable him to film the masts as they came crashing down. So fine did he cut his distance that they swept within a few feet of where he was standing.

The story’s action reached its highest point when Shackleton decided that, to conserve food, most of the crew should be left on Elephant Island.

He took Worsley and four other men into a small lifeboat called the James Caird. His hope was to find help at one of the whaling stations on South Georgia Island. It would be a treacherous journey, but they forged ahead, since the other option was to languish in the cold and starve to death.

These men would remain on the James Caird for seventeen days. Not only would they endure polar temperatures, they would also be constantly wet. They would survive on inadequate food. They would endure days without any fresh water—or ice—to whet their thirst.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Tearoom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.