Tertius Lydgate: Middlemarch's Modern Medical Man

Before the Victorian era, doctors prescribed dangerous substances such as opium or laudanum or resorted to unsanitary practices to prolong patient life and minimize suffering.

I’ve never liked doctors. As a writer, I am both overly sensitive to my own mortality and something of a hypochondriac; I find most American physicians either unpleasant or downright terrifying, and I’ll avoid doctors at all costs until a visit becomes absolutely necessary. But one doctor has always had my heart: Tertius Lydgate—literature’s first modern doctor.

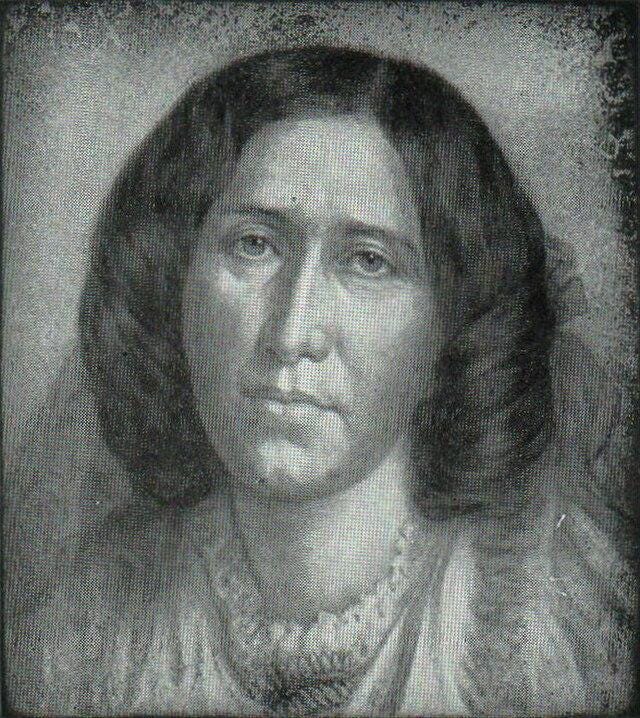

Until the 1874 publication of George Eliot’s Middlemarch, few works of literature had ever taken on the topic of medicine. Before the Victorian era, in fact, the practice of medicine was not only nebulous but also unscrupulous: given the industry’s lack of regulation, doctors frequently prescribed dangerous substances such as opium or laudanum or resorted to unsanitary practices such as bloodletting to prolong patient life and minimize suffering. By the mid-19th century, however, innovations in medicine ushered in a new wave of medical standardization and an overall increase in quality of patient care.

George Eliot was awestruck, and Middlemarch was born.

One might wonder at the ease with which Eliot captures the nuances of medicine in literary form, but the Victorian literary prodigy was no stranger to innovation—her unorthodox relationship with British philosopher George Henry Lewes catalyzed her love for experimentation and exposed her to the thriving world of medical discovery in both Britain and in mainland Europe. Though Eliot lived with the married Lewes out of wedlock (a practice that often made pariahs out of respectable people), his Regent’s Park home quickly became her haven for intellectual exploration.

Eliot obtained firsthand knowledge of the scientific discoveries of the Victorian era through her position as the chief editor of the Westminster Review. Her own interest in science, as well as her commitment to Auguste Comte’s positivism, an empiricist philosophical theory that directly influenced the scientific method, led her to spend her evenings reading Darwin’s On the Origin of Species aloud to Lewes every evening, inspiring the seasoned philosopher to branch out into the scientific world. Lewes’ first great scientific venture—an essay titled Physicians and Quacks—examined the relationship between psychological and physiological phenomena and argued in favor of “scientist doctors,” an emerging profession that envisioned doctors as researchers and laid the foundation for the medical practice as we think of it today. Physicians and Quacks soon won the admiration of Charles Lyell and Thomas Henry Huxley, influential scientists who worked closely together on the study of fossils and human history in the mid-1800s, and established Lewes as a respected scientist of the Victorian world.

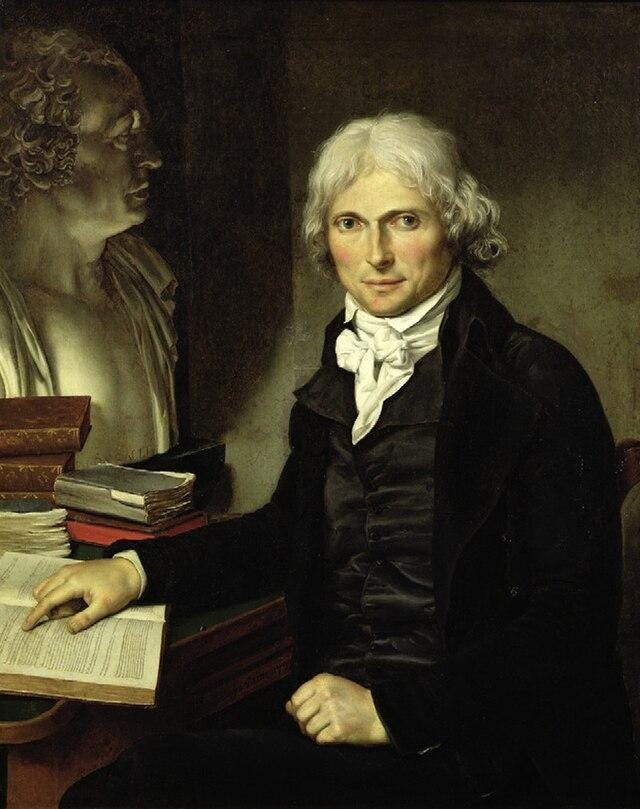

By 1870, Lewes, now a full-fledged scientist, became particularly fascinated by the brain and took a trip out to Oxford University with his lover to conduct neuroscience research. It was there that a professor of anatomy dissected a human brain for the young Eliot and sparked her interest in human psychology. Around the same time, Lewes spent several weeks in Bonn and Heidelberg discussing Marie Francois Bichat’s cell theory—the proposition that cellular tides were the basis of every organism—with anatomists Max Schultze and Nikolaus Friedrich. Taking a particular interest in the nerve cell, Lewes soon came out with a book called Problems of the Life and Mind.

This was the book that inspired Middlemarch.

After returning home, Eliot’s first and most important agenda item was the composition of what was to become the fifteenth chapter of her work—an introduction to Tertius Lydgate, literature’s first modern doctor. Bichat himself inspired the character of Lydgate, a young professional captivated by recent discoveries in French autopsy. Lydgate’s belief, in fact, that pathological methods are the key to promoting social good is the cornerstone of Bichat’s own work in cell theory, and like Bichat, Lydgate hopes to find the “primitive tissue underlying all structures.” He engages in basic tissue research to complement his medical practice and becomes the first doctor in literature to both treat patients and conduct research of his own—a detail that Eliot includes to emphasize the standardization of the medicine by the mid-19th century.

Indeed, before the 19th century, the medical profession was largely unregulated: virtually anyone could become a doctor, and, given the lack of formal legislature, the profession was dominated by the aristocratic elite and often corrupted by nepotism and other spurious practices. Under this system, doctors were often divided into three distinct roles: physician, surgeon, and apothecary. Physicians, typically university-educated and often serving the wealthy, were considered the intellectual elite of medicine. In contrast, surgeons—originally trained as apprentices and often regarded as manual laborers—occupied a lower social and professional status. Apothecaries, who dispensed medicines and provided some medical care, further added to the fragmented state of the medical field.

Reform efforts of the early 19th century, however, began to introduce stricter standards. In 1815, the Apothecaries Act in the United Kingdom mandated that aspiring medical practitioners pass exams administered by the Society of Apothecaries, marking one of the first attempts to formalize medical qualifications. Over the next decade, movements advocating for the regulation of the profession and the incorporation of the scientific method into medical practice gained momentum, with “Doctor’s Registration Movements” pushing for more standardized practices in diagnosis and treatment. However, it was not until the Medical Act of 1858, which established a register of qualified medical practitioners, that the truly “modern” doctor was born: doctors were now required to demonstrate their medical proficiency through standardized education and examinations, marking the formal professionalization of the field. By the mid-19th century, the unification of the medical profession had been achieved, with doctors and surgeons both subject to standardized education and examinations—a policy shift that marked the birth of the truly “modern” doctor. As Lewes’ “scientist doctor”—doctors who were also researchers—swept the nation, the modern physician emerged, blending intellectual rigor, practical skill, and scientific inquiry.

Eliot’s Lydgate is the epitome of such a modern doctor: he is an amalgam of surgeon, physician, and apothecary, treating both external conditions such as typhoid fever in Fred Vincy and internal conditions such as heart failure in Edward Casaubon. Trained as a surgeon in London and later Paris, Lydgate is Eliot’s representation of the dissolution of the elite College of Physicians as more surgeons began to cross over into the practice of physicians. In Middlemarch, Lydgate expresses the unapologetically progressive belief that diagnoses must come from scientific evidence; his willingness to listen to patients’ complaints, as well as his adherence to the Apothecaries Act of 1815, which prohibited the dispensation of drugs by doctors for financial profit, demonstrate not only his own status as a modern practitioner but also Eliot’s keen understanding of the scientific world around her.

Indeed, Eliot sends her young doctor to Paris for his education—a site of momentous research in the medical field at the time of Middlemarch’s composition. It is here that Lydgate acquires the majority of the medical knowledge he puts into practice throughout the novel, gaining familiarity with famous French physicians and scientists at the time. An intimate understanding of physician Pierre Louis’ studies on typhoid fever, for instance, allows Lydgate to identify Fred Vincy’s condition in its early “pink stage”; similarly, Lydgate uses René Laënnec’s newfangled stethoscope to diagnose Causaubon’s heart disease. Beyond his private practice, Lydgate also tackles public health challenges, observing the connection between London’s contaminated water supply and cholera outbreaks and calling out institutional corruption.

Determined to bring scientific medicine to the town of Middlemarch, Lydgate works for the New Fever Hospital in the hopes of establishing a special ward for cholera victims. He aligns himself with the Parliamentary Act of 1825, which authorized sanitation assessments, and envisions his hospital as a “nucleus” for a future medical school—a precursor to modern academic hospitals under Britain's current National Health Service (NHS).

Eliot, however, does not fail to call out the inadequacies of mid-19th century healthcare and the regressive attitudes that permeate Victorian society: However radical Lydgate may be, conservative forces ultimately thwart his vision for Middlemarch. His pioneering tissue research becomes overshadowed by practical concerns as he struggles with bureaucracy, social resistance to reform, and personal financial difficulties, illustrating the widening divide between scientist and doctor in Eliot’s world.

Setting out to become a researcher, Lydgate ultimately finds himself trapped by the realities of medical practice. Through his pioneering story, Eliot captures the tension between scientific idealism and medical pragmatism but does not leave us on a negative note. Though Lydgate fails in his tissue research and hospital reforms, his Parisian education, diagnostic skill, and commitment to evidence-based medicine align him with the modern doctor—a figure who, by the end of the 19th century, would become the standard in medical practice.

Middlemarch is thus not only one of the most important works of 19th century literature—it is also a seminal document on the history of medicine. And at a time when medicine was subject to radical change, Eliot presents us with Tertius Lydgate as the bridge between past and future—between medicine as a science and as an art form, reminding us just how intimately bound up medicine can be with humanity.

How the Post Office Created America

I have long been a fan of ‘snail mail,’ the practice of writing letters on paper. Using envelopes and stamps, we send tangible evidence of affection to family and friends. However, our mailboxes do not provide the same sort of thrill as in olden days; many approach it every day with a chagrin.

Thank you for writing about one of Eliot's best characters. Tertius is a tragic figure. To see him bringing about his own undoing by choosing the exact wrong partner always brings me great sadness when I read Middlemarch. I find myself imagining all that he and Dorothea could have accomplished. I do think it is Rosamond and not the realities of medical practice which is his undoing. When Eliot has Rosamond miscarry after being thrown from the horse, it seems a symbol of all the fledgling hopes Tertius might still have nurtured. I really enjoyed reading this!

👏👏👏 Such a masterful piece by the great Liza Libes! Thank you Mariella Hunt for publishing it! Middlemarch by George Eliot is one of the most important works of literature ever written which contains a timeless message about the clash between scientific progress and outside influences who for whatever reason, be it politics, religion or dogma wish to repress it. The 19th Century was a time when great change was taking place in the world of medicine. Mrs. Eliot capture’s this perfectly with the story of Dr. Tertius Lygate who fights for reform in the musical community and insists that medical evidence and the opinion of the patient be used as the basis for a diagnosis not guesswork or a loose hunch or one-off assumptions. He ultimately loses that battle but it’s a story that resonates in our time.

Think about how wrong the scientific and medical authorities got COVID-19 wrong. They the science behind it wrong, lied to the public about it and repressed any science 🧪 that disagreed with theirs. Dr. Lygate’s battle against the medical establishment of his time reminds me of the battle the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration and doctors like Robert Malone and Peter McCullough who spoke out about the inaccuracies behind the government and the medical profession’s assessment of the science behind the Coronavirus.

They were smeared mercilessly for doing so. Same with HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. with his Make America Healthy Again Initiative. He’s been smeared everyday from Sunday including by his own family for saying reasonable things like we should rigorously test vaccines to make sure their safe and effective, vaccine makers should not have a liability shield, seed oils and high fructose corn syrup are horrible for you, we should not allow companies to use artificial dyes that are banned in other countries in our food, fluoride should not be in our water, and big food makes our food as addictive as possible and that needs to stop.

For concurring with Copernicus’s view that the Earth 🌍 revolves around the Sun ☀️NOT the other way around, Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake and Galileo Galilei was put under house arrest for the rest of his life. Science 🧬 has also been used for evil purposes. The Nazis with the T-4 Program for example which murdered 300,000 disabled people. Or Eugenics which led to the sterilization of 60,000 people in state-sanctioned eugenics programs. Before the Nazis rose to power, it was America and England who pioneered the science they would later use to perpetrate the Holocaust.

Eugenics targeted criminals, alcoholics, prostitutes, disabled people, people with mental health issues, sexually active women, poor whites, Jews, African-Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and Eastern and Southern European immigrants. Some of the most respect people in American society supported it including Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Alexander Graham Bell, John Rockefeller, Sr., Margaret Sanger, and Helen Keller.

Another example, the Tuskegee Experiment which ran from 1932-1972 in which black men were deliberately left untreated for syphilis by the United States Public Health Service and the CDC who wanted to see the effects of the disease if left untreated. The results were absolutely tragic! 128 patients died, 40 patient’s wives were infected with the disease and 19 patient’s children were born with the disease. These men never gave their consent, were lied to, never told they were sick, and were denied treatment.