The Startling Eye of Emily Dickinson

She’s calculated to have written 1,775 poems. She is honored with other famous poets at the American Poets’ Corner.

February is about to begin. On this, the last Friday of January, we welcome our next guest to the Tearoom!

During the month of January, I featured Jane Austen, an author whose story I already had some fair knowledge of. I now turn to a poet I knew nothing about, other than basic facts.

She lived in New England. She’s calculated to have written 1,775 poems. She is honored, along with other famous deceased poets, at the American Poets’ Corner in the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, located in New York.

Learn more about Poets’ Corner, and the authors buried there, by visiting this site.

Emily Dickinson’s story is not what I expected. To be fair, I wasn’t sure what to expect; all authors of immortal works had personal lives loaded with surprises.

I didn’t know that Alcott was unhappy with her masterpiece, Little Women; most people would be surprised that Jane Austen turned down a marriage proposal, given that her works are immortalized as love stories (though, in truth, her work is so much deeper).

Like many authors, I’m a homebody. I go places when I have to; I’m not drawn to social situations. On the occasions that I do go out, I don’t enjoy chit-chat; instead, I spend my time observing others, wondering about them (though not enough to approach them).

I look for patterns and keep alert for stories that want telling. It has always been that way. People used to comment about how quiet I am, or quip about how I don’t really go anywhere.

(They still do sometimes; the difference is that I no longer care as much).

I’m only a bit reclusive. Emily Dickinson took reclusiveness to a new level.

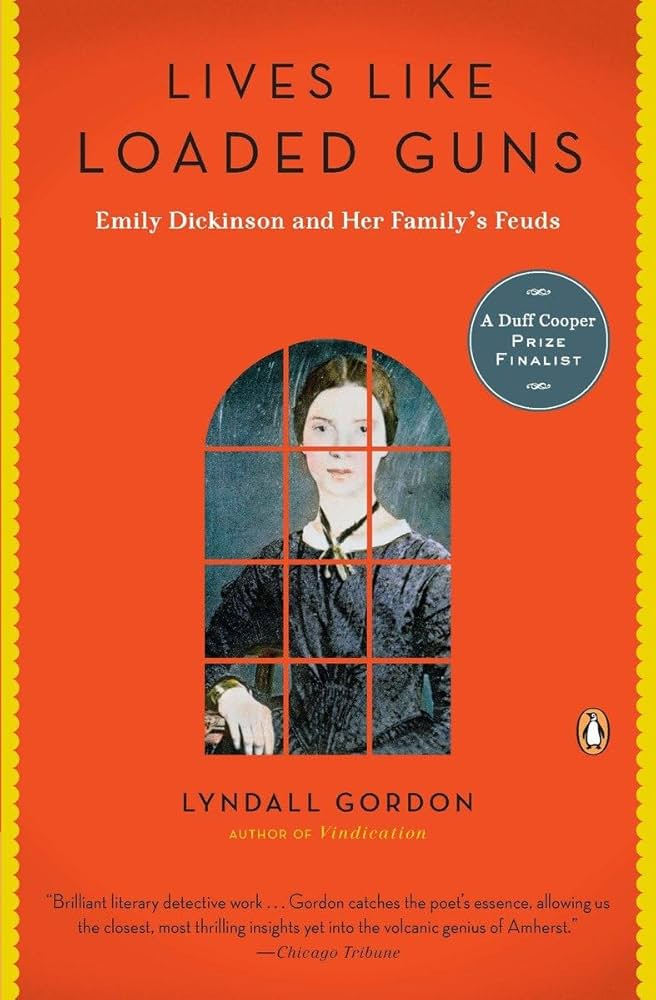

In the biography Lives Like Loaded Guns by Lindall Gordon, the introduction includes a comment by Emily’s neighbors that made me smile. They claimed that she hadn’t left the house in fifteen years. Was that true, or an exaggeration, as gossip tends to be?

Whether accurate or not, we cannot argue with the fact that Emily spent a great deal of time to herself, especially in her adult life. This was, in part, because Dickinson was prone to illness (though what exactly ailed her is up for debate; it’s never stated clearly in letters).

Emily Dickinson might have been a homebody, but she made a great contribution to the literary world. Her legacy can be found in her vibrant, poignant poetry. One might claim that she was a poem; she expressed herself best in verse, seeming only to trust a person if she thought they might appreciate her work.

Years later, she remains a mystery, but she has achieved fame that other poets only dream of. In spite of this, most of her work was not published in her lifetime.

Emily Dickinson was born December 10, 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her parents were Emily Dickinson, nèe Norcross, and Edward Dickinson. Her father was a politician with a sober personality, a disciplinarian.

Her mother is also a mystery; so far, I have only gathered that she was a ‘standard wife’ for the time, setting her dreams aside when she married, whether she wished to or not.

Mrs. Dickinson was also a fragile woman, prone to bouts of tears.

Her melancholy impacted all of her children, albeit in different ways.

I would venture to say Emily caught it directly; she, herself, would be a soul prone to angst and melancholy. She packed these emotions into poetry, becoming the most quiet and elusive of the three siblings.

Emily’s older brother, William, was born in 1829; Lavinia, known as Vinnie, was born in 1833. Their mother struggled with severe postpartum depression after Lavinia’s birth. Her husband took this into account and decided to mind his wife’s wellbeing; as a result, they did not grow a large family, defying the norm of the time.

So there were no children after Lavinia. In spite of that, Mrs. Dickinson continued to wrestle with turbulent emotions. On top of that, her marriage suffered when their family stopped growing. Emily would comment about how her parents’ relationship was distant and cold.

She wrote poems expressing negative thoughts about marriage, especially what was expected of married women. These passages from Lives Like Loaded Guns, a book which I will quote throughout this post, give an example:

Her daughter the poet would define a wife as one who rose to her husband’s ‘Requirement’, dropping ‘The Playthings of Her Life’, and if she missed anything in her day-to-day life it fell outside the accepted vocabulary.

[Emily]’s poems take a dim view of what it was to become a wife: ‘Born — Bridalled — Shrouded — in a day’.

But who was Emily, the daughter and poet? Is there a way of knowing what she was like in the comfort of her home, surrounded by people she trusted?

We have all seen her famous photo. It captures a pale young woman with wide eyes that seem to pierce into the viewer. One gets the impression that Emily knows things about them that they have yet to discover.

Lives Like Loaded Guns says of that image:

The well-known daguerreotype taken when she was sixteen bares the face of a person who, as her brother put it, ‘saw things directly and just as they were’. Her sister called it a ‘startling’ face.

Startling, indeed—but is it her face that startled people, or the sense that they were being seen?

Emily must have been one of those people who was not fooled by a facade. Humans love to wear facades, concealing weaknesses or truths in order to fit in. It would explain why Emily had trouble bonding with friends as a teenager.

I found myself commiserating with her: I’ve also been a writer, the quiet person in the room, the one who seemed more interested in seeing. It did not escape me that people seemed to shy away.

Emily’s experience was similar:

Emily did not take in the strangeness of unconcealed originality: ordinary girls of that age tend to be indifferent if not cruel to oddity, and especially so at a time when female ambition was odd in itself.

Oddity isn’t a bad word, but when you’re young and don’t yet understand the world, it can feel that way. I embrace my oddity now, but when I was a teenager, it was a struggle to understand why people did not stick with me for long.

The attention span of the young can be short and cruel. I find comfort in knowing it’s always been so; I’m not the only one who struggled. Emily, though, suffered far more. As already stated, she was prone to depression, and her disappearing ‘friends’ only made it worse.

Writers are often able to take the pain they feel, be it from abandonment or other reasons. They use that pain to create beautiful work. Emily Dickinson used her pain; from it, she wrung nearly two thousand poems.

Her words continue to startle us today, fixing us with the same sensation of I see you that startled those she met in life. Her poetry digs into us, an unwavering gaze; it forces us to release our secrets, because poetry will learn all things eventually.

Pure poetry, the kind that becomes immortal, will often make us uncomfortable. It causes us to ask why we hide our imperfections, because these imperfections make us unique. Why would we want to be like everyone else?

Coming from an old, prominent family, Emily always presented herself in a way that maintained the dignity of that family:

[Emily’s] one surviving dress confirms her continued simplicity. Her curly hair, cut short in her early twenties, was long again in her late twenties, parted in the centre and drawn back over her ears in smooth bands. The uprightness of her posture suggests New England correctness.

Yet, in spite of her simplicity with regards to appearance, Emily did not try to blend in and be like her peers.

Religion was a major cause of struggle. At boarding school, teachers would ask the girls if they were ‘saved.’ It was an indirect requirement to say yes. Other girls were quick to reply in the affirmative; Emily alone hesitated to raise her hand.

She was often at odds with teachers who disapproved of her hesitation, seeing it as rebellion. As a Christian, I understand why Emily was hesitant to reply. Salvation is a large matter.

She might truly not have known; she might have wished for time to examine herself. Or was there a deeper, hidden struggle that caused her hesitation? Some people think so; I’ll cover that later on.

In any case, this was a girl who picked apart people and places. A poet with her level of perception would prefer to explore such matters privately.

Emily’s teachers would not let the matter rest. She found herself in trouble so often due to the matter of religion, that she was assigned a roommate to keep an eye on her, reporting her behavior to her parents.

(No wonder she later decided that she preferred privacy—lots of it).

We take risks when we dare to be different. The world does not take kindly to people who don’t conform; indeed, in some situations, being ignored is the kinder of the two options.

I would much rather be left to my own devices. Let me be on my own; don’t try to squish me into a mold. Emily must have had that same thought and followed it to an extreme solution.

She decided she’d had enough of the world, that she was happy in the house with her thoughts. Neighbors didn’t like that, either, so they talked about it. Surprise! We just can’t win, can we?

Whether or not their fifteen-year claim is true, she was a homebody. She was not sitting idly, though; during her years of isolation, she penned hundreds of poems. She baked, gardened, read, and played the piano.

Emily might not have had much need for the outside world, but she saw her world; her inner landscape was vast enough that we still become lost in those verses.

What exactly drove her to extreme isolation? What was the illness she struggled with throughout her school years and into adulthood? Did she ever intend to publish her poems?

I will explore these questions in the posts to come.

Emily Dickinson is unique among the authors that I have researched thus far. In spite of her quiet nature, there is much to wonder about her. It’s been buried by time, only seen now by picking apart her poetry, when we dare.

What’s the phrase I once heard? It’s the quiet people that ought to worry you. Behind their silence is power that will draw from you all of your truths—the strongest, ugliest, even holiest.

Poets have a tendency to know. Emily learned that people don’t like to be known. She locked herself away, so they could not know her, even if they tried. For many years, the only way to ‘see’ her was through her words in the poetry that she shared.

Lives Like Loaded Guns is one of two Dickinson biographies I plan to read. I also have Alfred Habegger’s biography, My Wars Are Laid Away in Books. I have a feeling that, after I’ve read both of these, I’ll still have a sensation that I don’t know her.

Does one ever fully know a person, or a poem?

Thank you for joining me as I explore the life of this fascinating, puzzling figure from literary history. I am excited to uncover more. Already, I’ve found some parallels between her youth and mine; she speaks to me, while remaining elusive.

Have you read her poetry? Do you have a favorite? Please comment and let me know.

As always, if I’ve gotten anything wrong, feel free to correct me; I love to learn as much as I enjoy sharing what I’ve learned!

Louisa May Alcott: “Little Women” Is Born

The Civil War began in 1861 and shook every person living in the country. It was the result of years of political tension, and its many battles resulted in appalling numbers of casualties.

Your reflections on Emily Dickinson are both immersive and deeply perceptive. You capture not just the mystery of her solitude but the paradox of a poet who withdrew from the world, only to leave behind words that refuse to be ignored. The way you thread personal resonance with historical exploration makes this more than just a literary study - it’s an intimate dialogue with a mind that still startles us, even centuries later.

Your insights on the risks of being different struck a chord. Dickinson’s refusal to conform - whether in social life, faith, or creative expression - is a testament to the power of unfiltered introspection. It’s fascinating how those who retreat from the world often see it most clearly. Perhaps her reclusiveness wasn’t isolation but immersion - into thought, into language, into the unseen. You make me wonder: was her silence an act of surrender, or was it her boldest form of defiance?

“I’m only a bit reclusive. Emily Dickinson took reclusiveness to a new level.”

I FEEL THIS.

This was a truly wonderful read!