Author Liza Libes on ‘The Lilac Room’ & Edith Wharton

The beauty of literature is that, ideally, every person should come away from a given novel with their own impression of “the message” based on their distinct worldview.

Happy Wednesday, Tearoom patrons! I hope the Advent season is treating you well. My feet are freezing, but I’ve got plenty of good books to keep me warm.

Today I have a treat for you: a special guest has agreed to tell us about her story, as well as to offer her input about classic literature.

If you’re a frequent reader on Substack, you might have encountered her work. Liza Libes is a deep-thinking author, but I’ve discovered that she is also a great friend.

I can tell she’s got a remarkable career ahead of her. I’m fortunate to have the chance to collaborate with her! A post of mine about Louisa May Alcott is set to go live on her blog soon.

Check out Liza’s blog, Pens and Poison. She is currently querying her novel THE LILAC ROOM and hopes to get it out in print soon. This blog post is about her writing process, and the book in question; I can’t wait to read it!

—Mariella

Q: Where did you find the inspiration for The Lilac Room?

A: The premise of my novel THE LILAC ROOM is two-fold: on the one hand, you have an underlying thriller-type plot in the background that follows the suicide of a young woman named Rebecca Solomon, and on the other, you have the romantic entanglement of my main character Cassandra with a spurious FBI agent named Adam. These two plotlines increasingly converge the farther you make it into the novel and both underscore the novel’s principal social commentary on New York City’s elite class, as well as Cassie’s obsession with finding herself among the ranks of these “elitist, mathematically-driven circles,” as she aptly describes them. Each of these plotlines was inspired by events in my own life.

I was never as obsessed as Cassie with joining these nebulous Manhattan social circles, but I became aware of their existence on the subway one day several years ago when two of my friends (whom I had introduced to each other) were discussing a party they attended that had been featured in The New York Times. I was livid about their conversation for about a week and could not understand how I had also not been invited, yet the more I read about this party, the more I realized just how decadent and morally questionable these sorts of events were, and I had the idea to write a story where a similar party would lead a girl to suicide. Thus THE LILAC ROOM was born.

The novel’s romance plot was inspired not by my own life but by that of a former friend: she had a guy chasing after her whom she chronically deemed too “beneath her” to be with, and I started to think about the sorts of ridiculous standards that we set on people when it comes to choosing life partners. My friend insisted that the guy had “no class” (this later became one of the novel’s most telling lines that leads into some of Cassie’s concluding remarks about Adam) and that no one in polite society would ever date him. I got to thinking about this idea of “polite society” and came up with the idea of Adam, an uncouth outsider from deep in Brooklyn who has no idea how to behave around Manhattan socialites. Adam is the catalyst for Cassie’s own transformation as she realizes that “high society” isn’t everything and falls in love with someone she might deem a “simpleton.”

Adam is named, of course, after the world’s first man: innocent and unworldly, with no idea how to conduct himself; as he loses his innocence, he discovers shame. In a way, his character is a direct reflection of his namesake in Genesis.

Q: Are you a plotter or a pantser? Do you switch styles between drafts?

A: I am a pantser all the way. Going into the novel, I only knew everything that I described above. The rest came to me as I was writing. I had no idea why Rebecca would commit suicide or whether Cassie would end up with Adam. I only knew that there was going to be a party that affects Rebecca and that there was going to be a vague love plot between Adam and Cassie. The rest filled itself in as I went. I listened to an interview once with a well-known author (can’t remember for the life of me who it was) who once claimed that the mark of a good writer was that your characters come alive on the page and start making decisions for themselves. That’s exactly how I felt when I was writing these characters. I would routinely get angry at Cassie for the way she treated Adam, and I chided Adam for being such an idiot around Cassie. Sometimes, I would be out in the world and hear something that felt like it would be ripped right out of the mouths of my characters and then rush to write a chapter. I once met someone who claimed to have stayed at the Ritz so many times that he kept a box of Ritz slippers in his closet.

Similarly, I once dated a guy who got a surgery to remove the sweat glands from his armpits because he wanted to look more professional at work and always ended up sweating through his clothes. These ideas both made it into my novel.

In a way, the novel is a reflection of the progression of my own life. Stylistically, I’ve had the most trouble combining the first and second halves: I wrote the first half about two years ago and then took a break to query my other novel MAN A MUSEUM. When I came back to the second half of the novel a year later, some muse had breathed a strange spirit into me, and I wrote the entire second half (about 50k words) in just a month. The second half feels a bit more feverish and impassioned, while the first half is more observational. I’ve tried to go back and give the first half a bit more of the touch of passion because, ultimately, that’s the spirit I want to go for in the novel.

Q: What would you like for your readers to learn from this novel? What message do you hope that they will take from it?

A: The beauty of literature is that, ideally, every person should come away from a given novel with their own impression of “the message” based on their distinct worldview. I hope that I’ve written a novel that leaves something for everyone, and I hope that Cassie’s decision at the end will leave some readers frustrated and others satisfied.

Without giving too much away, here are some questions that I hope my readers will consider after finishing the book:

How does ambition shape our relationships? At what point does ambition become a negative?

What drives Cassie’s obsession with elitism?

What does the novel suggest about the corporate world?

I can’t tell you what happens at the end, but I hope that my readers will forever mull over Cassie’s decision and wonder how it reflects on their own lives.

Q: Do you have a favorite author? Have they influenced your writing life?

A: I talk a lot about William Faulkner, and while he is my favorite from a literary perspective for his experimental style and insight into the human mind, I don’t think he’s had as much influence on my writing as one of my other favorite authors, Edith Wharton. Edith Wharton has to be literature's most underrated female author—you always hear talk of Emily Brontë and Virginia Woolf and Toni Morrison when it comes to the female beasts of the literary world, but no one ever mentions Edith Wharton—and they damn well should. Wharton’s The Age of Innocence perfectly captures the spirit of the Gilded Age in New York City. The novel opens in an opera house and speaks to the romantic in me while providing a sharp satire on New York society. In a way, my novel accomplishes the same feat: provide a sharp satire on New York society while creating a sense of atmospheric opulence; in fact, the setting of the second chapter of my book—an Upper-East-Side party thrown by two wealthy New York socialities—was inspired by the world of The Age of Innocence.

But Wharton is not only known for her commentary on high New York society. Her slightly lesser-known novella, Ethan Frome, for instance, is set in the countryside and follows a trio of simpler characters—simpler in means but not the least in psychology. Ethan Frome changed my life because it was one of the first books that I’d read that left me feeling incredibly angry. I can’t tell you why because I don’t want to spoil it, but a book has to be brilliant to elicit an emotion like that.

I’ve been deeply inspired by Wharton and hope to write a novel that scholars can compare to The Age of Innocence someday. Wharton is one of my most important literary role models and occupies a unique position in literary history as one of few American female novelists of the early twentieth century.

Q: Do you have a preferred era of literature? Which books are your favorites, and why?

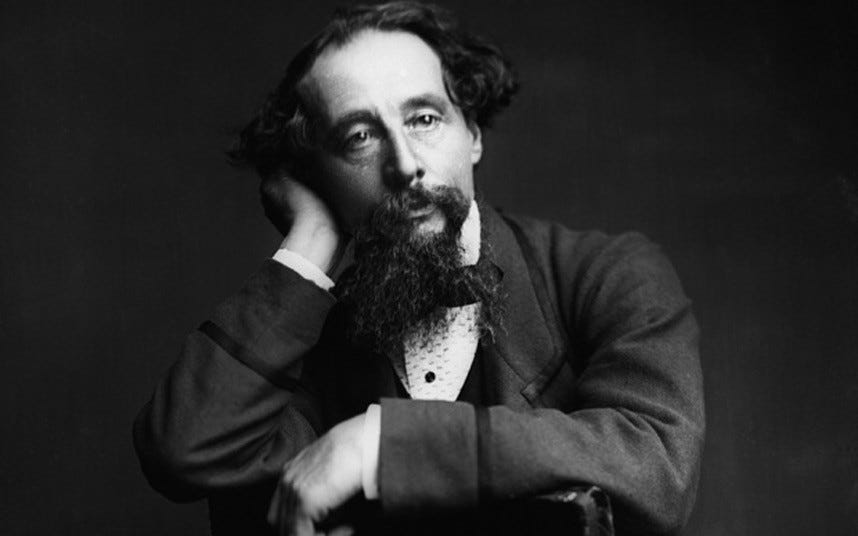

A: 1870-1920—late Victorian to early modernist. In high school, I was a staunch Victorianist, and though the early Victorian era still produced some of my favorite books of all time (Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Vanity Fair), the modernist movement caught my attention for its profound commentary on human psychology. The Victorians, one could argue, were more psychologically repressed, so by the time that repression began to erode in the 1870s, novels shifted from the characteristic realism of Charles Dickens to a more nuanced commentary on human psychology. The 1870s, of course, gave birth to George Eliot’s Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda, Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now, and Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd. These are some of my favorite books of all time because they provide not only a sharp societal commentary but also an insight into the human mind. The final decades of the 1800s produced some of my favorite works, and the turn of the century, of course, gave us Edith Wharton. I still love many books written after WWI, but something was ruptured in the human soul after the so-called Great War, and literature was never the same again.

If you’re looking to get started with this era, check out Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence (1920) and John Galsworthy's The Forsyte Saga (1906). These are some of literature's most underappreciated books and flawlessly capture the spirit of the early 20th century while providing a haunting commentary on decaying societal mores. I embody this spirit in my own work: there’s something ethereal about it that draws me in—the last vestiges of the old world before our current descent into technological advancement and modernity.

Charles Dickens: The Man who Reinvented Christmas

“You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Thank you so much to Mariella Hunt for this fascinating interview with Liza about her brilliant upcoming book “The Lilac Room!” Liza is one of the most intelligent, perceptive and passionate people I have ever known. Her love for literature knows absolutely no bounds and she clearly was born to be a writer. What Liza describes in this interview is a book that would easily outsell and be more interesting than any piece of contemporary literature on the shelves at Barnes & Noble today! “The Lilac Room” is the book we need right now as people are starved for great, well-written literature with something more than identity politics in it. It’s not the identity of the characters or the social justice nonsense in a book that make a work of literature great. It’s the underlying message in it, the universal themes it explores and the characters and how they develop. That’s why books like A Farewell to Arms, The Great Gatsby, Dracula, Frankenstein, The Wizard of Oz, The Catcher in the Rye, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Old Man and the Sea, The Grapes of Wrath, and Of Mice and Men and the poetry of William Shakespeare, Robert Frost, G.K. Chesterton, and T.S. Eliot will stand the test of time while nonsense like The Hate U Give and Bad Feminist will not. I don’t know about you, but I’ll take James Joyce or James Baldwin any day over anything Sally Rooney or Judith Butler has written! Classism, elitism and seeking to fit in are timeless themes that mankind will always grapple with. Liza mentioned that World War I seems to have changed mankind forever. I think what the Great War did was it showed humanity how awful they could be to one another and the depths of depravity we as a species can truly reach. This interview was so much fun to read! Liza can hold you spellbound on her every word like no one else I know can! Whenever I see a note by her on Substack or I watch one of her videos from YouTube I’m immediately intrigued to find out what she will say or what her opinion on a given topic will be! The characters of the Lilac Room are clearly sophisticated, well-rounded characters with interesting backstories. The Lilac Room I’m certain will be like a nice cool pitcher of water poured onto the dry desert of the literary world! To Liza’s point about Edith Wharton, she definitely is a very underrated writer. Mrs. Wharton also lived quite a fascinating life as well. I’m convinced if Edith Wharton were alive today, she’d be intrigued by “The Lilac Room” and seek to obtain a copy and read it when it was officially published. Liza follows in a long tradition of great female writers stretching back centuries. You should definitely check out Pens and Poison if you haven’t already! Also, go read her article she wrote for The Black Sheep publication!