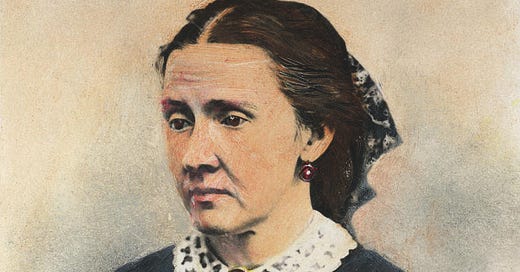

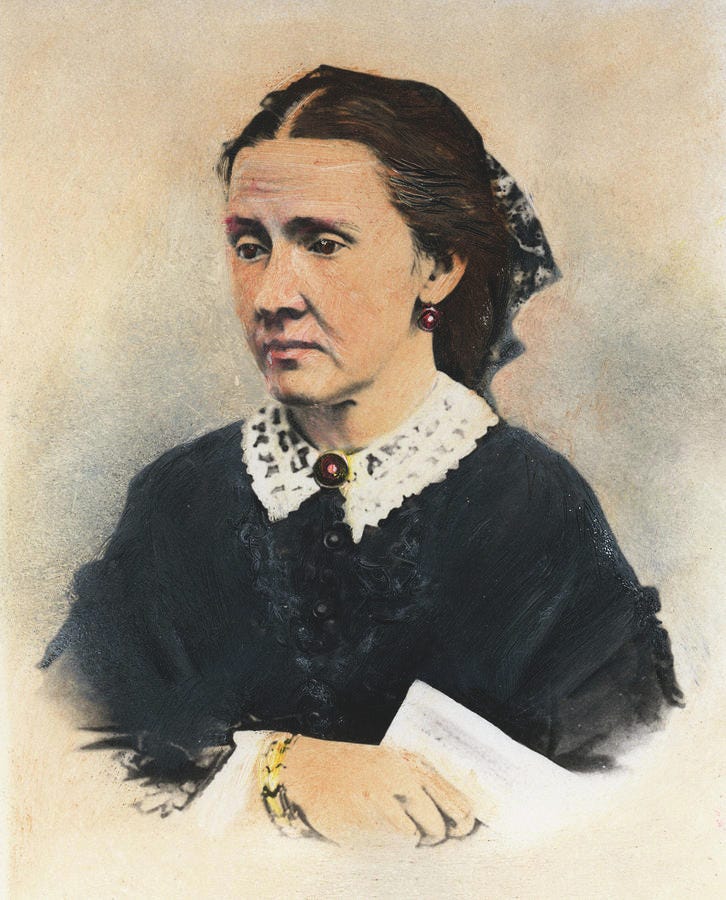

Battle Hymns: The Middle Life of Julia Ward Howe

An article about the writer of 'The Battle Hymn of the Republic.'

I’m not going to lie, summarizing any life of nearly a century, particularly one so full as that of Julia Ward Howe, is daunting. Thank you so much, Mariella, for allowing me to split my humble effort. Even split thus, the Julia I can show you, the poet of The Battle Hymn of the Republic, is only but half her story.

My last essay ended in 1839, at the death of Julia’s father the Banker, often referred to as her “jailer” in private letters and journals. At the time she and four of her siblings were still living at the great mansion on the corner of Broadway and Bond Street, New York City. Her oldest brother Samuel had recently moved out with his young bride, Emily Astor (yes, those Astors, and they thought they had married up).

In any other family, orphaned “children” aged 15-21 would have been expected to carry on themselves, but none were prepared to step into the Banker’s shoes and be responsible for the mansion and family fortune. Enter, Uncle John Ward.

Perhaps my favorite quote, p. 31 from my primary text, Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910, written by her beloved daughters, has this to say of Uncle John:

Uncle John also tried to censor Julia’s reading, but the ‘damage’ was already done— brother Samuel had returned from his European tour with enough books to require a new library be built onto the house! Though Uncle John tried to forbid Faust and Shelley and such, he was out of his league, she had already read them. More importantly, she was reading Balzac, George Sand, and Lamartine.

French fiction, at this time, was pushing boundaries, especially in the exploration of gender. By the time Uncle John arrived, Julia had already translated Lamartine’s Jocelyn and published upon it anonymously! The tale concerns a young man fleeing religious life during the French Reign of Terror, who falls in love with a beautiful boy, whom he eventually discovers to be a girl. You guessed it, Jocelyn is not something proper young American society ladies were supposed to read. It is said that Uncle John objected only on the grounds that Julia should spend more time learning housework, but I suspect that was because he hadn’t read it.

Then, tragedy. Just as the household should have been lifted from mourning the Banker’s death, Julia’s closest brother Henry would die of typhoid fever. Already unmoored, if not overly in mourning, Julia was overwhelmed, even wishing she had died with him.

For a time, 21-year-old Julia would combat this grief leaning heavily on her father’s Calvinism. She may have even become a bit of a religious tyrant to her siblings! I so adore that she could admit that. Gradually, however, the darkness would lift. Reading Milton, studying Transcendentalism, and meditating (she lay awake mornings “visioning” regularly throughout her life), she would begin to fear God less and love Him, and His creations, more.

And then, there were the parties. Oh yes, Julia could dance the night away, then next morning rise to study philosophy! The social calendar of the young Wards encompassed not only New York and summers in Newport, but by 1842 included extensive stays in Boston. Since 1837 one of Julia’s greatest friends had been Mary Ward (no relation), whose father was also in banking, and who loved to host lavish affairs there. Mary had been engaged to Henry at the time of his death in 1840, which would endear her as a sister in Julia’s eyes forever.

Mary Ward knew everybody, especially in Boston literary and Transcendental circles. Emerson, Margaret Fuller, even Longfellow became trusted friends. And with Longfellow came intrepid abolitionist Charles Sumner.

To say I’ve been sitting here staring at that name for an hour is not understatement. So much has been made of this moment in Julia’s life, this man’s role in her marriage, it’s hard to know what is history and what is the lens with which we are currently viewing it. I’ll include some bibliography at the end of this essay, as I was compelled here to engage more than the gentle biography of Julia written by her daughters.

What is for sure is that Charles Sumner, often austere to the point of parody, would talk on one topic effusively— the extraordinary work of Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, the Greek war hero whose pioneering work at the Perkins Institute for the Blind included the first successful teaching of a student both blind and deaf. On a day Sumner surely would regret in the summer of 1842, he suggested he and Longfellow could take the Ward girls out to meet Howe and tour the Institution.

Off they went in a large carriage, to meet the man friends and admirers called Chev, or Chevalier, as he had deservedly received what amounted to knighthood for his role in Greece’s fight for freedom from Turkey (he even owned Byron’s helmet, bought at regimental auction). They arrived just in time, the Doctor was riding toward them— thick black hair, shining black horse, blue eyes, and all.

I wish I could say that’s all folks, they lived happily ever after. Affluent young lady poet meets a real knight-in-shining-armor fiercely dedicated to good works, wedding bells within a year.

It’s never that easy, is it? For Julia was not only a poet but a philosopher; from her text on Lamartine’s Jocelyn, it’s clear she thought love should be truly Platonic, that is, one soul finding its true mate, its true other half. The problem is, at least to some degree, Chev had already found his sympathetic soul, his other half, in Charles Sumner. Letters written to Sumner assuring his marriage to Julia took nothing away from his affection, letters about missing him terribly while on his honeymoon, are heart-wrenching.

It’s clear she and Chev fought. He admitted to Sumner that she had said Sumner should have been born a woman so those two could have been married! And yeah, Chev kinda admitted she was right.

Despite all this, Julia truly had fallen in love with him, and wanted a home and family with him, and he at least had strong esteem, extreme good-will for her, and had a strong desire for children. Within twelve years she would bear him 6 children, five of whom would survive to adulthood.

And yet Julia struggled through early married life. After the honeymoon she confessed that of all the rooms in the Bond Street mansion, she couldn’t even describe the kitchen! Still, she made a joyous home for her brilliant children, who adored her, even if the only kitchen craft she perfected was buttering bread. All she asked was her daily “Precious Time,” to read, to write, to think. Intrusion was kept to a minimum by her cheerfully working in a wasp-filled attic.

This struggle to balance her own needs, her role as a mother, and a complex, sometimes extremely cold relationship with the “roaring lion” she married seemed to overwhelm Julia the first three years, but in 1847 she would write to her sister Louisa that her world was re-awakening. It was at this time, later biographers would discover, she was writing her own story of gender ambiguity, The Hermaphrodite.

No, I have not read it yet, I’ve had to Gary William’s excellent scholarship on this point (see bibliography). From his perspective, I gather that over time and in secret, Julia wrote and rewrote pieces of this tale in part to explore the difficulties between her, Chev, and Sumner, as well voice her thoughts on gender roles ala Margaret Fuller, Swedenborg, and George Sand.

She was also writing poetry, publishing first Passion-Flowers in 1854 and then Words of the Hour in 1857. At some point I will write on her poetry further, for now let me say it is truly fearless, full of love, loss and politics in equal measure, the latter work even calling for the impeachment of the President. At this time, she would also write the play The World’s Own. Chev was not pleased, but she was learning that his displeasure was worth heeding her muses and asserting herself. She also began giving musical parties, singing and playing with the elites of the day.

At this time also, war was in the air. In 1851 Charles Sumner was elected to the U.S. Senate to fight for Abolition, desegregated schools (100 years before Brown vs. the Board of Education), peace with Mexico, and prison reform. Meanwhile Chev worked behind the scenes, his expertise at raising funds for these same causes is legendary.

Then, Bloody Kansas. Please read about it, I can’t say much in this short space. To enter the union as a state, Kansas was required to declare itself a free or enslavement state, and lives were lost in the settling of the issue, in battles of “volunteers,” and covert assassinations. Rising up out of this conflict stands one towering figure, for good or ill, John Brown. It is probable that Sumner and Howe met him in 1846 when he moved briefly to Massachusetts and sure that they considered him a worthy ally in the fight for Abolition.

Did Chev raise money for Brown, yes, nearly working himself to exhaustion. Did he know or agree that money was spent on weapons for Brown to try lead a slave uprising, I would not be surprised. Sumner did his part giving an extensive speech in the Senate on May 19,1856 in support of Kansas becoming a free state and decrying slaver Senator William Butler by name.

On May 22, 1856, Representative Preston Brooks, cousin to William Butler, beat Charles Sumner nearly to death on the Senate floor while radical secessionist Laurence Keitt held off the crowd brandishing a pistol.

Please read that sentence a few times. If you are an American, this should hit you like a brick.

Word of this attack galvanized radical abolitionist John Brown further during the time of Blood Kansas. Mere paragraphs cannot describe this enigmatic true believer who considered himself something of an American Moses sent to free the slaves. Angel or madman he, I cannot tell you. I do know he came back to Boston in 1857, more money was raised, more guns acquired. As soon as Kansas was settled as a Free State, Brown stepped up his game.

John Brown was captured after he led an attack on the Federal armory at Harpers Ferry on October 16, 1859, intending to free enslaved blacks and arm them. After capture he made it clear he preferred martyrdom to rescue. On December 2, after a show-trial, he rode out on top of his own coffin and then walked himself up to the noose and was hanged, the first hanging for treason in American history.

That fall, Chev feverishly fundraised for Brown’s legal fees and help of his large family. At least once we know Julia sat and cried and prayed with Brown’s wife Mary. Every pulpit and newspaper had something to say about Brown, and Julia despaired that she would ever be able to say all that was in her heart about him.

Why do I tell you about this? Well, soon on the heels of Brown’s execution came full scale Civil War. Chev helped Massachusetts amass some of the first volunteer regiments and he would go to the battlefield to apprise officials concerning supplies and medical needs there.

And so, by Autumn 1861 Julia would find herself with friends in Washington D.C., going out to see the troops at the parade grounds. While returning into town, those troops overtook her carriage on their way back to barracks. While they waited for the companies to pass, she and her friends regaled them with the war songs of the moment, including “John Brown’s Body.”

Oh, how I wish I could have heard her resounding mezzo-soprano, her extraordinary projection and delivery! One of her companions suggested she write a better song to the popular tune that day, and she replied that she had been considering it. The next morning a long poem to the right meter presented itself complete in her mind. That poem was The Battle Hymn of the Republic.

I’m going to stop here, hoping I’ve met my goal to bring the poet of The Hymn into view. The truth is, Julia Ward Howe lived two lives, and the one which comes after this, after her husband’s death, is one of philosophy, preaching and suffragist activism, of an extraordinary woman coming into her own. If asked I will return perhaps next month to tell that tale.

And so let us close, as almost every gathering she attended closed whether she liked it or not, singing The Hymn itself. Please do read all the way down, it has more to say than the few familiar phrases.

And remember, she wasn’t somehow “cheating,” as Wikipedia intimates, by using the tune to “John Brown’s Body” (which in turn had come from the slave spiritual “O Brothers”). It was in deference, to Brown, Chev, Sumner, and all those fighting for freedom and justice. And yet it is very much a Hymn, for to Julia Ward Howe, every righteous victory belonged to God.

The Battle Hymn of the Republic by Julia Ward Howe

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He has loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword;

His truth is marching on!

Chorus:

Glory, glory, Hallelujah! Glory, glory Hallelujah!

Glory, glory, Hallelujah! His truth is marching on!

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read his righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on! (Chorus)

I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel:

“As ye deal with My contemners, so with you My Grace will deal;”

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel,

Since God is marching on! (Chorus)

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgement seat;

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him, be jubilant my feet!

Our God is marching on! (Chorus)

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me.

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on! (Chorus)

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave,

He is Wisdom to the mighty, He is Succour to the brave,

So the world shall be His footstool, and the soul of Time His slave,

Our God is marching on! (Chorus)

Simplified Bibliography:

Elliot, Maud Howe: Uncle Sam and His Circle.

Howe, Julia Ward: Passion-Flowers, Words of the Hour (both poetry), The World’s Own (play), Reminiscences (autobiography), in order of publication.

Richards, Laura E. & sisters: Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910.

Tharp, Louise Hall: Three Saints and a Sinner (about Julia, her two sisters Louisa and Annie, and “sinner” brother Sam)

Williams, Gary: Hungry Heart: The Literary Emergence of Julia Ward Howe. See also his “Speaking with the Voices of others: Julia Ward Howe’s ‘Laurence’” University of Idaho, available online.

Such an interesting woman! The timing of this is wild, as just a couple of months ago I put out the history of the Kansas territorial struggle I finished years ago. I’m eager to learn about Julia Ward Howe’s life after the Civil War.

What a wonderful continuation of her story—the ins and outs of someone’s life so well captured really makes for captivating reading!