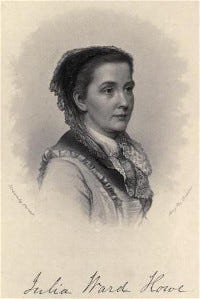

‘Neath a Clouded Star: The Early Life of Julia Ward Howe

A guest post by Litcuzzwords

“I was born ‘neath a clouded star,

More in shadow than light have grown;

Loving souls are not like trees

That strongest and stateliest shoot alone.”

(Excerpt from To the Poets, by Julia Ward Howe, from her first poetry collection, Passion-Flowers)

What an honor it is to be invited to Mariella’s Substack! And look, what an honorable plus-one I have brought to the affair— musician, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, preacher, peace proponent, women’s rights activist, Julia Ward Howe.

Actually, she wasn’t my first choice. I first thought of her daughter, poet and (mostly) children’s book author Laura Elizabeth Howe Richards, who had settled in my home community after her marriage and left a lasting mark for the good there. I quickly discovered, however, that anything I could write about her would be so very personal that it would be better suited for my own workspace here on Substack.

I only had to look so far as her mother Julia for an apt replacement. And lucky for me, Laura and her sister Maud wrote a 440-page biography about their mother, Julia Ward Howe: 1819-1910. Many thanks to the Bates College and Bangor Public libraries for loaning me their fragile treasure.

Yes, I know there are a few in-depth, slightly controversial renderings of Julia’s life in print just now. My purpose here, however, is to introduce you to this particular book as well as its subject, a book which garnered a Pulitzer Prize. Does it perhaps gloss over a troubled childhood and challenging marriage, probably. Her daughters tried their best to tell the story they knew, and ended up with an incredible look at nearly a century of politics, wars, literature, philosophical study and religious thought, without dishonoring anyone involved. And that’s what their mother would have wanted. A word of caution, I’m afraid the beginning of her life is quite a strange and sad tale.

If you know Julia Ward Howe, you probably only know her as the writer of The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Oh yes, I know, she only wrote the lyrics! Wiki dissed her for that, which bristles me considerably, but I’ll contain myself for now.

To say that Julia Ward was born to NY royalty might even be an understatement. Her parents came from three great Revolutionary War families, the Wards, Greenes, and Marions, plus one intrepid Dutchman who changed his name from Demesmaker to Cutler for convenience. Her father, Samuel Ward III was a New York banker— actually THE New York banker, in so many ways. First president of the NY Bank of Commerce, one of the founders of NYU and the Stuyvesant Institute were just a few of his accolades and responsibilities. In 1836-37 he would work day and night to “prevent the dishonor of the banks of New York (p. 29), rebuilding the system after the economy of the city crashed, and personally acquiring the $5 million loan from the Bank of England on behalf of his firm, Prime, Ward, & King. Julia would remember the arrival of the gold bars with great awe.

At this time, with the help of Aunts, nannies, and tutors, Samuel Ward was doing his best to raise six children, Samuel Cutler, Henry, Julia, Louisa, Francis Marion, and Anne Eliza, alone after the death of his wife, Julia Rush Cutler, who died of complications after the birth of Anne Eliza in 1824.

Speaking on a life so full as Julia’s, it’s tempting to, like nearly all historians of yore, to pass by her mother, alive only until Julia was six. But I knew Mariella would not have it, nor should she. Of Julia Rush Cutler Howe, the biography has this to say:

“Her life had been pure, happy, and unselfish; yet her last hours were full of anguish. Reared in the strictest tenets of Evangelical piety, she was oppressed with terror concerning the fate of her soul; the sorrows of death compassed her about, the pains of hell gat hold upon her. It is piteous to read of the sufferings of this innocent creature, as described by her mourning family; piteous, too, to realize, by the light of to-day, that she was almost literally prayed to death. She was 27 years old when she died and had borne seven children.” (P. 8)

Julia was only six when her mother died, and remembered her as a great light in the household. When that light was gone, her father sank further into his lifelong depression and leaned heavily into his Calvinism. To say the mood in the household was dark, well, when the children learned of the illness of a beloved little cousin, she and her siblings sent not Get-Well cards but a note urging the child to get right with God lest he meet with the horrors of hell. In it she would exhort her cousin to love God so that he could look at the approach of death with joy.

As Julia, the eldest of the girls, grew, she found that her father also leaned heavily on her. She was always to sit to her father’s left at table, and often as he ate, smoked, talked, he almost absentmindedly clasped her right hand, sometimes for the entire meal. As one was supposed to only eat with the right hand, she would sit in silence and eat nothing. Little else quite so poignant and disturbing can be said about Samuel Ward, I’ll just lay that image here.

The biography also tells us that underneath Samuel Ward’s stern and austere parenting lay a “very anguish of solicitude, this passionate wish that they should not only have, but be everything desirable and lovely…” (p. 15).

No pressure. The children had dancing masters, though they weren’t allowed out to dances; they played for music tutors, who discovered Julia’s great talent at piano and voice. They trained her magnificently, though she could not go out to the opera (ok, she snuck out a couple times).

At their opulent home on the corner of Bond Street and Broadway Samuel Ward even built a home museum, a long “picture gallery” larger than some public museums of the time. “The children might not mingle in frivolous gaiety abroad, but they should have all that love, taste, and money could give them at home; he filled his gallery with the best pictures he could find” (p. 18).

His quest for the perfect children went so far as to insisting red-haired Julia go heavily veiled outside to play at their Newport summer home, for fear of freckles. Every single time.

At age sixteen Julia would end formal schooling, and thanks to her brothers’ access to books, could really begin the more “vigorous” study for which she craved, while yet continuing disciplined musical education. This time, she said herself, was also marred by “morbid melancholy, which threatened to upset my health” (p.20). Her father’s passion for perfection was scarring her, leading her, at sixteen, to take up the study of German and having herself tied to a chair to be sure she achieved her daily learning goals.

I think these anecdotes may be enough to speak to her situation, but not to young Julia Ward herself. Like her maternal aunts and cousins, Julia had an extremely quick mind and an independent spirit. She would long remember what her elderly cousin Nancy Greene told her, “When you feel that you CANNOT do a thing, GET UP AND DO IT!” Eventually, she would do just that. Tired of her father refusing to let her come “out into society,” 19-year-old Julia would ask her father if she could have some friends over for an evening. He acquiesced, and she organized her very own ball underneath his nose. With the guests arrived and the hired orchestra playing, the caterers at their stations, there wasn’t much he could do but enjoy the evening.

Soon after this, the Philadelphia banking system failed, and the institutions there began begging New York for assistance, even to the point of suspending any trade competition. This Samuel Ward knew would bring NY tumbling down again, and this he would not have. Unfortunately, he had pneumonia and was supposed to be resting at their Newport home. Instead, he returned and “threw himself into the fray” (p.30). He would save New York and put into the works a means of allowing Philadelphia’s recovery, before coming home to Bond Street and dying, his hand clasping Julia’s.

These few events as I have told them give us much concerning the home life which shaped her, yet all this does not speak to the amazing mind and extraordinary talents which allowed young Julia Ward such relief from the stressors about her. Her sisters remembered her ability to spout rhyme and meter on the spot, and her music tutors marveled at the liquid dexterity of her fingers on the keys, her ever-perfecting voice. Deeper than all that, however, lay a visceral desire to understand the depths of literature and history, and particularly philosophy and religion. This would, of course, require reading in several languages— don’t worry, French, Italian, German, Latin all soon became like old friends, she studied voraciously and diligently until she read, sang, wrote, and spoke them all, even Latin, with ease for the rest of her life.

And yet, what have I truly said about Julia Ward Howe? I fear I have brought a mere shade into view. I am so thankful that Mariella has allowed me to split this visit in two! I shall return forthwith and speak to her incredible adulthood, but for now at least we can understand Julia when she herself speaks of the next phase of her life, in contrast to her childhood. The text, from her first book of verse, Passion-Flowers, is the opening of the first stanza of Rome, an ode to her first time abroad as a young bride:

“I knew a day of glad surprise in Rome,

Free to the childish joy of wandering,

Without a ‘wherefore’ or ‘to what good end?’

By querulous voice propounded, or a thought

Of punctual Duty, waiting at the door

Of home, with weapon duly poised to slay

Delight, ere it cross the threshold bound.”

I look forward to seeing you all here at Mariella’s quite soon, to share so much more about Julia Ward Howe. I think you shall find her as wondrous as I do. Take care.

Mary Shelley: An Introduction & Her Dream

We have a new guest at Top of the Page this month! For, what else can I call it when a character knocks at the door, insisting to be let in? Insisting to be ‘interviewed’? Insisting that it is now her turn to be heard?

Fascinating story!! I love the intricate histories that lay just off the beaten path so much more than the over-shared tales.

Oh, this was such an interesting and informative read, despite it containing such sadness. I look forward to the second part with much anticipation.