Beatrix Potter’s Lost Love

Beatrix Potter’s first love was a tradesman. Her parents were averse to the idea of her marrying down.

Read more of my articles by visiting my Table of Contents! Click here!

When I joined Substack last September, I wasn’t sure what I would do here. Having eased out of Kindle Vella, I considered myself only a fantasy author. I never pictured myself enjoying the process of writing nonfiction.

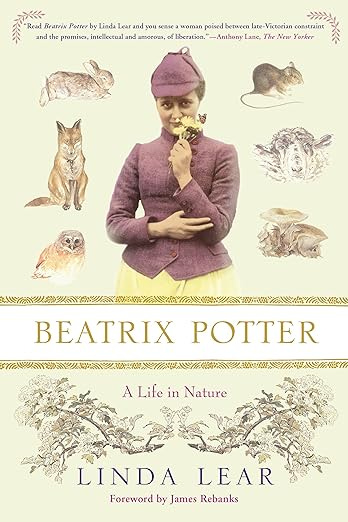

Not long before that, I had finished Linda Lear’s biography of Beatrix Potter, A Life in Nature. It remains one of my favorite nonfiction books.

Having been surprised by the life of Beatrix Potter, I had an idea. Perhaps other people would enjoy learning about the authors behind the classics!

In this article, I will quote several passages from A Life in Nature. Purchase a copy here!

I have since explored the lives of many authors, from Shelley to Dickens. I have ventured into art history and American history. Literary history continues to be the topic I write most naturally.

It started with Beatrix Potter—everything did, because her book is the first I can remember being read to me by Grandma. As a child, I never thought The Tale of Peter Rabbit would one day unlock a new beloved hobby, but here we are!

While studying authors’ lives, I uncover treasure troves of information. These people might have written classics, but they were human beings. Sometimes their stories are glorious; more often than not, they’re messy.

Events, happy and sad, creep into many of their fictional works. In most cases, a reader would only notice the parallel if familiar with the author’s past.

Charles Dickens’ novels are influenced by poverty he himself endured. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein seems to reflect the pain she felt after losing her first baby.

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is famous for the plotline of Beth’s death. This might not have been such a powerful scene, if Alcott had not also experienced the loss of a sister.

Beatrix Potter is different. We do not expect to find such difficult themes in her work. The Tale of Peter Rabbit was written for children who do not know many emotions that adults experience. Children do experience heartbreak, but I don’t expect it to be associated with romance.

That’s why it surprised me that Beatrix Potter had two love stories, the first of which ended tragically.

Beatrix Potter’s first love, Norman Warne, was a tradesman. Her wealthy parents were averse to the idea of her marrying down. Rupert, her father, took pride in his status as a barrister. Her mother, Helen, was a product of the times; she insisted that things were done a certain way.

At first, I was frustrated by Beatrix’s continued choice to obey her parents, even after she entered her thirties. Then I remembered that I live in a very different culture. Today, we have more freedom to choose; the taboos, though still around, are usually not so binding.

Beatrix was not born into a world where she had choice. Mrs. Potter kept a strict eye her daughter, even after she became a published author.

Reviews poured in praising her work, but that did not matter. Mrs. Potter insisted that, when Beatrix had to see her publisher, a chaperone should tag along, often Mrs. Potter herself.

Ultimately, these efforts did not work; Mrs. Potter might’ve sent all of the chaperones she liked, but her daughter’s mind—and heart—worked differently.

It might be that Beatrix did not exhibit the typical, outward behavior of a woman falling in love. She might have disguised these feelings to appease her mother. This does not mean she wasn’t falling; quite simply, her decisions tended to be thought-driven.

Beatrix had shown herself to be different at a young age by taking an interest in mycology—the study of fungi. I also had the impression that she was not a woman who fell for just anyone. She required a soulful connection.

Beatrix found this with Mr. Norman Warne at her publisher’s office, probably with her mother sitting in the room.

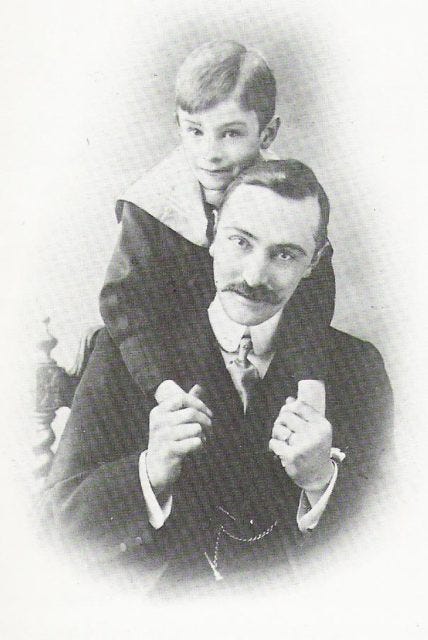

He was an editor for Beatrix’s publisher, Frederick Warne & Co. This firm had published The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1902 to great success. Once it became apparent that Miss Potter was not only a talented storyteller, but also an outstanding artist, they were eager to publish more.

According to Linda Lear, Beatrix seems to have fallen for Norman’s mind:

As they discussed the evolution of her books and the step-by-step process by which they were designed and produced, she realized that his tactful criticism almost always improved her work. She was grateful for that, as well as for his practical advice.

They must have shared stories about their families. In time, Beatrix began referring to him by the nickname his nieces had given him, ‘Johnny Crow.’

Their bond seems to have become strongest in 1904, when she was developing a new story about mice. Norman, who dabbled in woodwork, had built his nieces a dollhouse.

After learning of this, Beatrix asked him to build a house with a clear wall for her pet mouse. She could then observe the mouse’s behavior as a reference for illustrations.

Aware of Norman’s carpentry skills, Beatrix asked him to make her a new box for Hunca Munca, the female mouse, who was an especially good artist’s model as well as a sweet pet. Beatrix wrote to Norman, referring to him as ‘Johnny Crow,’ … ‘I wish “Johnny Crow” would make my mouse “a little house,” … I want one with the glass at the side before I draw Hunca Munca again. Mine are apt to be ricketty [sic]!’

Norman was happy to build the house. It was luxurious for a mouse, even featuring a nesting loft.

Before long, the mouse had moved into her new home. Beatrix began to draw. Meanwhile, her parents—particularly Mrs. Potter—grew suspicious of Warne’s friendship.

Helen Potter did what most women of high standing at the time would’ve done. She made it as difficult as possible for Beatrix and Norman to spend time together, inventing trivial reasons to prevent her daughter from visiting the office.

…it was becoming increasingly difficult for her [Beatrix] to visit the Warne office when Norman was there. Although she does not give specifics, there had been more unpleasantness at home about her frequent trips to Bedford Street, the inconvenience to Mrs. Potter’s schedule and perhaps even open disapproval of the relationship.

Even these attempts of sabotage were unable to break their bond.

Beatrix must have suspected that Norman would formally ask her to marry him before she left for the summer holiday. … She sent Norman her summer address in Wales as of Thursday, 27 July. On that same Tuesday, Beatrix did indeed receive a letter from Norman formally asking her to marry him. Then 39 years old, she accepted his proposal.

Rupert Potter now joined forces with his disapproving wife. He objected fervently to having his daughter enter “a union with a family ‘in trade’. His [Norman’s] was precisely the sort of family and social status they [the Potters] had worked to distinguish themselves from.”

Beatrix made an agreement with her family that there would be no formal announcement.

That summer, before the Potters left on holiday, Beatrix and Norman exchanged promise rings. They agreed to keep in touch; she planned to write every day, sending illustrations and new ideas that might come to her.

Mr. and Mrs. Potter must’ve been racking their brains for a way to end what they thought to be so much nonsense. Unfortunately, they would not need to take action; Norman was already sick with an illness that made itself known after the Potters left.

Though theories abound, most believe Norman suffered from leukemia. He was ordered to bed rest on 29 July, five days after proposing to Beatrix. The physician did not know exactly what was wrong. Seeing that it was serious, he advised the family to prepare for tragedy.

In this time, did Norman seek comfort in the tales he and Beatrix explored? Did he find refuge in her imagination, exploring Mr. McGregor’s garden, thinking with fondness of the home he’d made for Hunca-Munca?

As Norman’s hours slipped through his fingers, Beatrix remained unaware of his illness. She kept herself busy while on holiday, writing words to send him. Her ‘holiday diary’ entries are heartbreakingly optimistic. She had every reason to believe she would return to plan a wedding.

On 24 August, Beatrix reports, she’d gone into the woods, having received news that Norman was ill. On the morning of 25 August, a telegram arrived informing Beatrix that Norman was dying. She was asked to return to London.

That day, Norman Warne died. I like to imagine he was wearing his promise ring. I like to think that he imagined the afterlife, picturing his beloved Beatrix’s illustrations—verdant meadows and bright, blue skies.

The Potters finally left Wales on August 27. Beatrix reached London in time for Norman’s funeral. Perhaps I am too invested, but I wonder if Rupert and Helen Potter breathed sighs of relief.

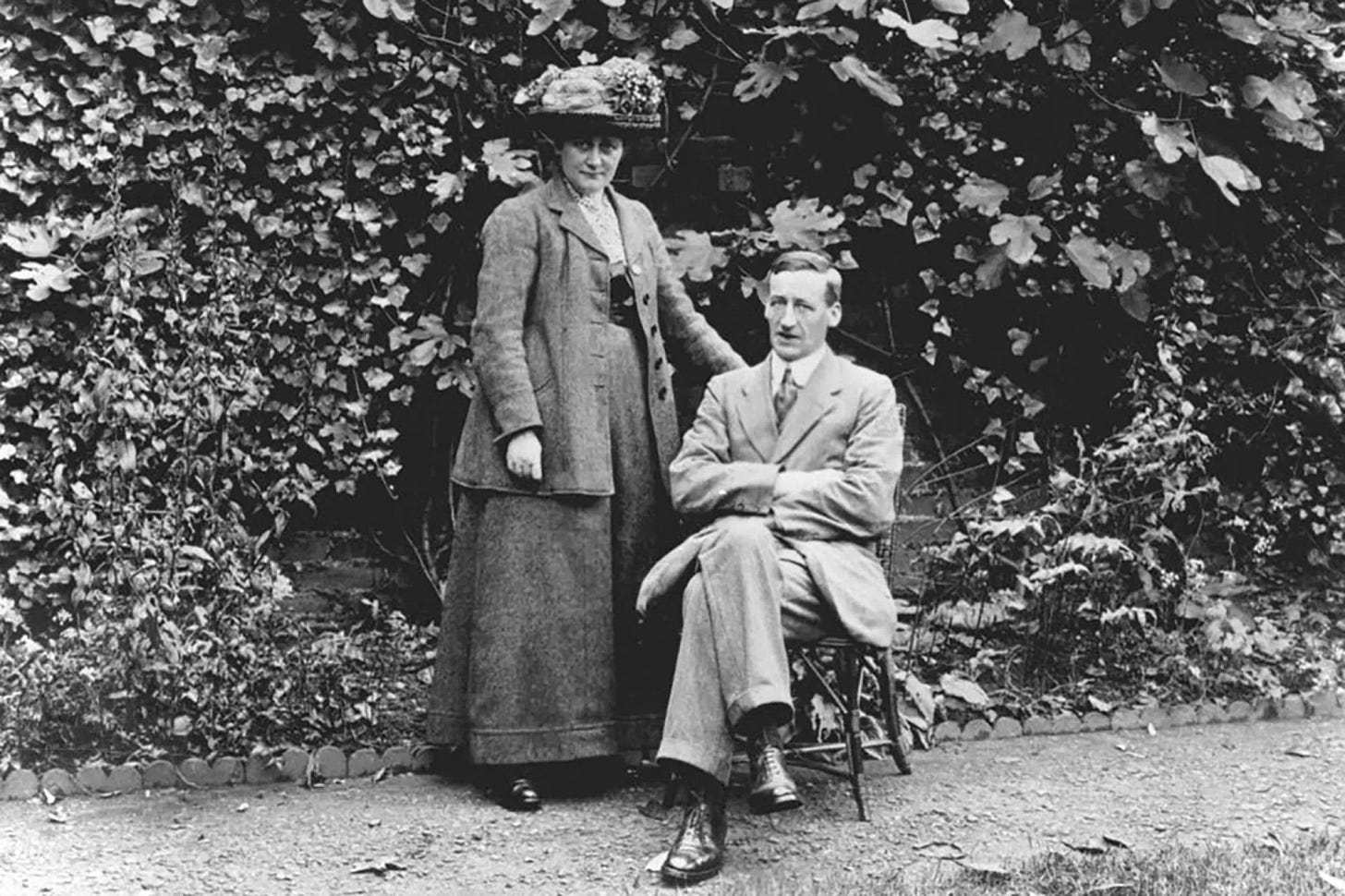

Beatrix Potter found love again at the age of forty-seven. By 1913, she was a successful woman in her own right, independent for the time. She’d gone to live on her own in a home she could decorate as she pleased.

As she settled in, she met and married a solicitor named William Heelis.

The Heelises lived in a village called Sawrey near the Lake District, where Beatrix became a prize-winning breeder of Hardwick sheep. She built a life she wanted, perhaps to compensate for what was denied to her by her parents’ obsession with appearance.

Beatrix Potter Heelis died at the age of seventy-seven on 22 December, 1943. Her husband took care of the legacy she left behind, managing her properties, ensuring that the Heelis sheep were always best in competition.

William was a faithful companion. He honored her memory, preserving her legacy after she had died. It is good to know that Beatrix Potter did have a love story in the end.

Mr. William Heelis remained devoted to her until his death on August 4, 1945.

I am glad that Beatrix did find love, but I can’t help wondering what would have transpired if Norman had not died. I’m too much of a writer to not spin alternate endings in my mind.

Such is the head of a writer, fiction or nonfiction.

Thank you for reading this article! I am still working through John Adams; it’s so much longer than expected. I might be writing something about his daughter, Nabby, soon.

If you are following The Graveyard House, I believe that book one will be finished in a little over a month. After that, it will be paywalled, and I’ll work on publishing it as an eBook later this year.

Your support and critique are both appreciated; please leave comments, give ideas, and tell me how February has been treating you!

I often wondered about the lives of authors whose books I have read. Sometimes I do make an effort of finding out more, but not always. So I really liked reading this fascinating piece about Beatrix Potter's life.

Marvelous. I remember in my pre teen years every christmas on telly there was a Ballet from UK Royal Ballet society, a direct translation from the swedish would be ‘Beatrix Potter’s fairy tale world. The dancers in animal costumes. A super thing. No words, just dancing animals. I remember loving it.