E. T. A. Hoffmann: Author of ‘The Nutcracker’

Since ‘The Nutcracker’ is best known as a theatrical play, many might not know that it began as a short story.

This article features quotes from The Nutcracker and the Mouse King by E. T. A. Hoffmann.

During the holidays, anyone who steps outside will find themselves surrounded by traditional signs of Christmas. From strings of lights to Starbucks flavors, the only way to escape this holiday would be holing yourself up at home and keeping the television off.

What I enjoy most about this time of the year are the stories. While familiar to most of us, they take on new life each Advent. Christmas stories continue to be written today in different settings, but they cannot compare to the classics—tales that have been read by our parents and grandparents before us.

Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol might be the most famous Christmas story, but it is closely followed by The Nutcracker.

Since The Nutcracker is best known as a play to be watched at the theater, many might not know it began as a short story—a delightful one, at that. Well-written and compelling, it brims with magic similar to what I’ve found in A Christmas Carol.

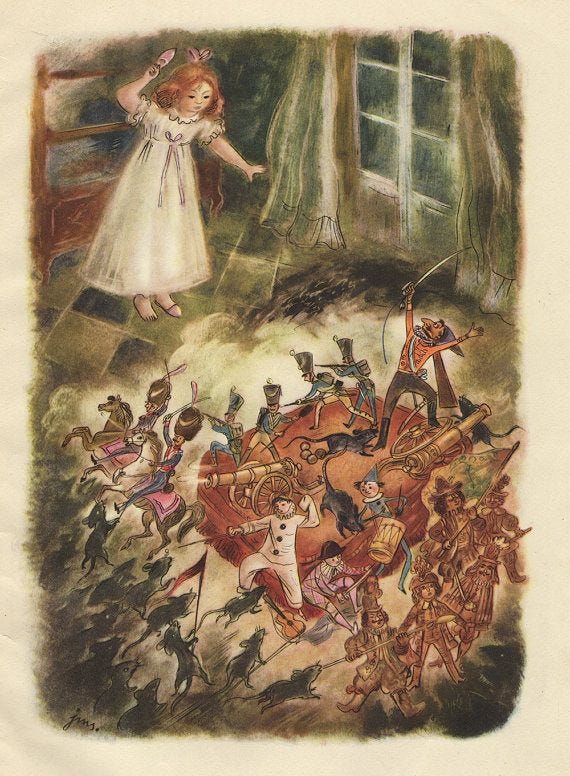

And Mouse King and mice squealed and shrieked, and they again heard Nutcracker’s tremendous voice issuing useful orders, and they watched Nutcracker as he marched over the battalions standing in the line of fire.

— from The Nutcracker and the Mouse King

A Christmas Carol and The Nutcracker are both driven by male characters. These characters are responsible for chaos, though one is more of a villain. Both stories are colored with elements of Christmas: traditions (or a lack of them), cold nights, and gifts that characterize the season.

Dickens’ A Christmas Carol features Ebenezer Scrooge, an old man who despises Christmas and is content to live life with no friends or holidays. The Nutcracker has Drosselmeier, godfather to Marie, the seven-year-old protagonist. He appears every Christmas with strange toys that enchant the family.

As a reader, I noticed a peculiar darkness to Drosselmeier: he has ill-tempered moments during which he appears to be a different person. It is no wonder, for he does have a secret.

Today, I thought we might offer a spotlight to Drosselmeier’s author, E. T. A. Hoffmann. He was a prolific writer whose tales shone with originality. He inspired many authors who would come after him, including Hans Christian Andersen.

Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann was born 24 January, 1776 in Königsberg, Prussia, to Christoph and Lovisa Hoffmann, nèe Doerffer. He was the youngest of the three Hoffman children. The second Hoffmann child died in infancy.

Christoph and Lovisa’s marriage was troubled, leading to their separation in 1778. Christoph left to Insterberg with their eldest surviving son, Johann. Ernst struggled with the void left by the disappearance of his father and brother.

Ernst was raised by Lovisa and her family: two aunts and an uncle, Sophie, Charlotte, and Otto Doerffer. During this time, Ernst took lessons in music and drawing. He also began to write stories.

However, life in Otto Doerffer’s house was pietistic and stifling for a child of Ernst’s age. It was not uncommon to bring up children in a strict manner. They were expected to excel at lessons and to keep quiet.

Children were commonly punished—often with the belt, or worse—if they misbehaved.

Ernst’s younger years, therefore, were bleak. Though he recalled his aunts with affection, he was vocally opposed to the way children were treated, and how it was accepted by society.

He thought children should be allowed to play, using their imaginations as he was unable to do as a boy. This was a motivator for stories that he would write later, stories that children and adults could enjoy.

In The Nutcracker, Marie and her siblings are children; they are also the protagonists, brave and ready to fight the Mouse King.

It’s full of playful description, told in such a manner that the magical happenings feel normal to readers. This is magical realism perfected; it makes us forget that the world, in reality, is often unexciting.

Marie could no longer contain herself. “Oh, my poor Nutcracker! My poor Nutcracker!” she sobbed, snatching her left shoe and, not quite aware of what she was doing, she flung her shoe into the thickest squad of mice—at their king!

Though a talented author and musician, Hoffman was a flawed man. He was described as moody and unpredictable. In 1794 he began a romantic affair with a married woman named Dora Hatt, one of his music pupils. She was ten years his senior and a mother.

Hoffmann proved to be such an annoyance that, after Dora gave birth to her sixth child, her family intervened. He had no choice but to relocate, asking one of his uncles to find him employment in Glogau, Prussian Silesia.

In the early 1800s, Hoffmann married Marianna Rorer, who went by her shortened name of Mischa. They had one child, a daughter named Cäcilia, who would unfortunately die as a child.

It seems that their first years together were peaceful; then, war broke out.

On 28 November, 1806, Napoleon captured Warsaw, where the Hoffmann family was living. Ernst sent his wife and daughter away to the Polish province of Posen for their safety. He himself stayed behind, searching for employment.

As the war continued, Hoffmann’s passion for writing and music thrived.

In 1809 he published his breakthrough story titled Ritter Gluck. He elected to use the pseudonym E. T. A. Hoffmann, with the A standing for Amadeus in honor of his hero, Mozart.

Hoffmann’s choices once more became questionable at this time.

In 1810, he was hired as a stagehand at the Bamberg Theatre, where he also offered music lessons. He found himself infatuated with one of his young students, a thirteen-year-old singer named Julia Marc. When Julia’s mother found out, she made his behavior known, finding a different tutor for her daughter.

In light of this scandal, Hoffmann was offered work elsewhere. A friend gave him the position of musical director at an opera company, which was at the time working in Dresden.

This new employment began in April of 1813.

“Am I not a foolish girl,” she said, “to be so easily frightened, and to think that a wooden puppet could make faces at me? But I love Nutcracker too well, because he is so droll and so good tempered; therefore he shall be taken good care of as he deserves.”

Hoffmann succeeded as a composer when his opera, Undine, was performed in September of 1814. He became a popular figure, sought by many for interviews and performances.

His fortune waned in 1819 when he found himself caught in a series of legal disputes.

Not only that, but he had contracted syphilis. It caused weakness of his limbs in 1821, which worsened to paralysis in 1822. His final work had to be dictated to a secretary, as he could not well utilize a pen.

E. T. A. Hoffmann died at the age of forty-six on 25 June, 1822. His life was tumultuous, and he made many questionable choices. In spite of this, he remains known for The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.

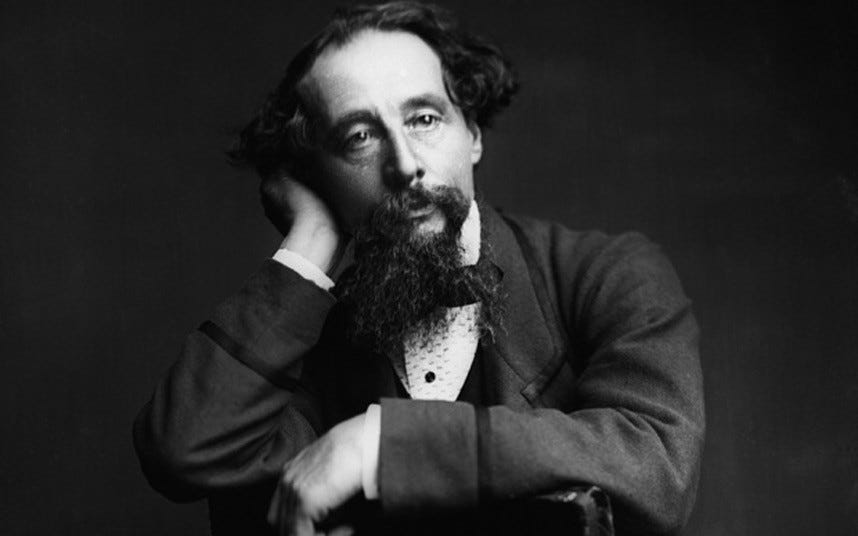

In many respects, he reminds me of Charles Dickens. The author of A Christmas Carol made questionable decisions in his personal life, even as he wrote masterpieces of literature.

While Hoffmann’s name is not so well known as Dickens’, we cannot escape those wooden soldiers that march onto our shelves and crawl up our trees each year in December.

The Nutcracker remains one of the most popular theatrical plays of all time. If you have not yet read the short story, do; I found it delightful. It’s a quick read, so you won’t have trouble carving out time for Marie’s adventure.

Don’t forget to put your nutcrackers someplace nice; they, too, might one day come to life.

Charles Dickens: The Man who Reinvented Christmas

“You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Thank you for sharing this!

Such an interesting read, thank you for sharing Mariella! The Nutcracker and the Mouse King will definitely be on my list of books to read next Christmas. 😊🎄