In Her Own Words: What Mary Wollstonecraft’s Early Letters Reveal

Mary’s letters underscore her bright mind and her doing what young girls her age did in Georgian England.

Prior to publishing A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft had written two advice books about raising daughters, a novel in which a heroine styled like herself pushes back against society’s rules for women, a pamphlet admonishing a powerful English politician, and scores of book reviews for the Analytical Review, a progressive London periodical. She also wrote a profusion of letters to friends, family members, and lovers. In them the woman widely regarded as the mother of feminism revealed the deepest part of herself.

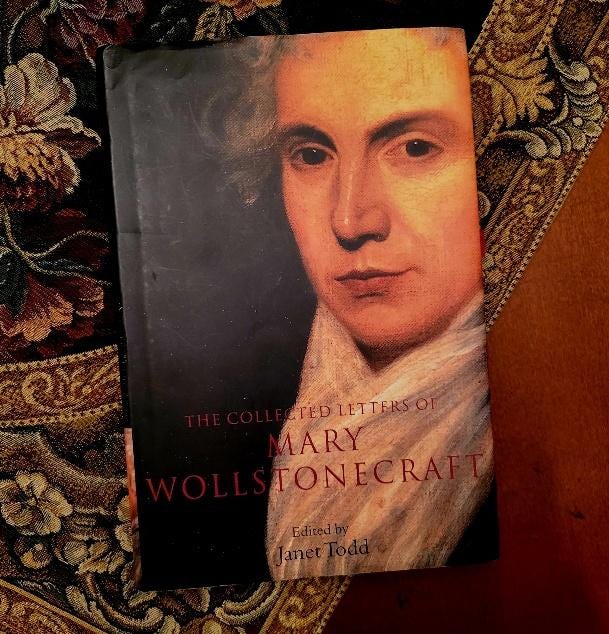

Mary’s letters alone are a fascinating read. In Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft, biofiction that captures the last ten years of Mary’s life, I include excerpts from a handful of letters she wrote in adulthood. To gain insight into who Mary was at her core, I relied on The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd.

Mary’s earliest letters show glimmerings of the firebrand philosopher she would become. Frankness and persistence were signature characteristics even in her teens. We have Mary’s friend Jane Arden to thank for saving the letters she received from young Mary.

Mary met Jane Arden in Beverley, England, a rural town in Yorkshire. The Wollstonecrafts moved to Beverley in 1770, but Mary’s letters to Jane do not begin until three years later when Mary is fourteen and Jane is sixteen. The lines below from the very first letter we have of Mary suggests their acquaintance is new. We also sense Jane has dazzled Mary, who seems eager to impress:

“Dear Miss Arden

According to my promise I sit down and write to you … I assure you I expect a complimentary letter in return for my staying from church to day. –

“I should likewise beg pardon for not beginning sooner so agreeable a correspondence as that I promise yours will prove, but from a lady of your singular good nature I promise myself indulgence. –”

Mary was precocious. Jane appears to have been her intellectual equal, an important association for Mary to have outside of her family, who offered little in terms of academic stimulation. The Wollstonecrafts were members of the landed gentry, but Mary’s father, Edward, abused his wife and children mentally and physically. An alcoholic with an addiction to gambling, by the time he brought his family to Beverley, this son of a wealthy master silk weaver from Spitalfields was well on his way to squandering the family fortune.

However, Beverley proved to be an emotional and educational boon for Mary, who had not yet attended formal schooling. Her mother, Elizabeth, her sole teacher until the family arrived in Beverley, was quick to criticize and curtail Mary, who was outspoken and exuberant. Elizabeth would punish Mary by making her sit in silence for up to four hours at a time.

This must have felt like cruel punishment to Mary, an energetic child accustomed to playing boys’ games with her brothers, exploring the forests alone, or walking along hedgerows, her mind wandering. She was not your typical girl. Already she felt shackled by society’s strict code of behavior for young women, yet she longed for her mother’s affection and tried to please her. Elizabeth turned a cold eye toward her eldest daughter and expected Mary to help with tasks related to raising Mary’s six siblings.

Despite Elizabeth’s detachment, Mary protected her with ferocity. Edward Wollstonecraft was vicious toward his children but particularly brutal toward his wife, often raping and beating her after a night of drinking and gambling. By the time Mary was twelve, she began sleeping outside her mother’s bedroom door to protect Elizabeth from his late-night violent outbursts.

Home being tyrannical, it isn’t surprising Mary attached herself to the entire Arden family. Jane’s father, John Arden, a traveling lecturer who taught mathematics and philosophy, took immediate note of Mary’s precocity and began teaching her alongside his own children. A busy, learned man like Arden taking time to groom Mary’s capabilities when girls’ education placed accomplishments over academic prowess must have boosted Mary’s self-esteem. Her scholarly abilities blossomed in Beverley, where she also attended a girls’ day school for approximately three years. It was the first and only school she would ever attend.

Mary’s letters underscore her bright mind and her doing what young girls her age did in Georgian England. She wrote poems and plays, learned to dance the cotillon, played quadrille, a popular card game, and read widely. She and Jane also discussed the books they read. Mary was a voracious reader and exhibited mastery of complex texts.

Though they lived in proximity and must have seen each other frequently, Jane and Mary exchanged letters, as was customary in the days before phones and texts. Mary’s missives (we do not have copies of Jane’s; Mary never saved them) are filled with en dashes, which suggests she wrote quickly, her mind racing faster than her pen. Mary’s penmanship slants forward as if in a rush. Her letters contain grammatical errors and misspellings, possibly stemming from her mother’s inadequate instruction. She apologized for her lack of neatness in a letter to Jane:

“I have just glanced over this letter and find it so ill written that I fear you cannot make out one line of this last page, but you know, my dear, I have not the advantage of a Master as you have, and it is with great difficulty to get my brother to mend my pens: – I am at present in a dilemma, for I have not one pen that will make a stroke, but however I will try to sign myself.”

As these lines hint, Mary is aware of her lack of formal education alongside what Jane has received, but that didn’t keep Mary from expressing bold thoughts in her letters. She didn’t hold back on giving Jane advice (in later years she would lecture her siblings, hoping to foster their self-improvement), gently chastising her (as she would anyone in her line of fire in future years), and openly lamenting her sorrows (most especially to her lovers when she became a woman, but also to anyone she chose to confide in). In her letters, Mary was an open book.

An example of this is when a fissure seems to have erupted between Mary and Jane in the fall of 1774. Mary expresses her frustration over Jane choosing to spend time with another girl rather than her:

“Miss A. – Your behavior at Miss J – s’ hurt me extremely, and your not answering my letter shews you set little value on my friendship. – If you had sent to ask me, I should have gone to the play, but none of you seemed to want my company. – I have two favors to beg, the one is that you will send me all my letters; – the other that you will never mention some things which I have told you.”

Mary had likely confided in Jane about her difficult life at home. Now she wanted Jane to keep what had been said between them a secret, for she feared she had lost Jane’s friendship.

Mary was prone to ruminating. I picture her having had time to reflect on the matter late at night, worrying she had gone too far in chastising Jane. She wrote to Jane again:

“Before I begin I beg pardon for the freedom of my style.” – If I did not love you I should not write so; – I have a heart that scorns disguise, and a countenance which will not dissemble: – I have formed romantic notions of friendship … I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have first place or none.”

The last line portends how Mary would react later in life to the men she loved. Mary’s desire to be “first” shows a need to feel valued and prioritized, the deep and unconditional love sorely lacking at home from her parents. It also suggests insecurity and a fear of being abandoned, anxieties Mary would carry into adulthood.

She is, however, an astute observer, and a quick study. Mary seems to have concluded that she had been wrong in her reaction to Jane. But only “partly.” In a subsequent letter after Mary received a missive from Jane, Mary wrote back:

“I have read some where that vulgar minds will never own they are in the wrong: – I am determined to be above such a prejudice, and give the lie to the poet who says –

‘Forgiveness to the injured does belong

But they ne’er pardon, who have done the wrong’

and hope my ingenuously own myself partly in fault to a girl of your good nature will cancel the offence – I have a heart too susceptible to my own peace ...”

Mary then added to the letter the prophetic line, “Love and Jealousy are twins,” understanding at her tender age how complicated affection could be between friends. She seemed genuinely hurt by Jane’s letter. But she could not let go of her sorrow. Before she signed off, in a PostScript she added:

“P.S. I keep your letters as a Memorial that you once loved me, but it will be of no consequence to keep mine as you have no regard for this writer. –

There is some part of your letter so cutting, I cannot comment upon it. – I beg you will write another letter on this subject … I inclose the Essay upon friendship which you papa lent me the other day. I have copied it for it is beautiful … Friendship founded upon virtue Truth and love; – it sweetens the cares, lessens the sorrows, and adds to the joys of life …”

Whew. The anguish Mary feels! Their exchange, at least from Mary’s side, sounds a little like a modern text war between teens, does it not? Mr. Arden apparently saw fit to intervene by lending Mary the article on friendship, a sign of his sincere investment in Mary’s development.

Did the girls patch things up between them?

It seems they did, but how and when isn’t clear, for shortly after this round of letters, Mary’s family moved to Hoxton, and no record of Mary and Jane exchanging letters occurs again until 1779.

Mary’s relationship with the Ardens proved pivotal to Mary’s formation. John Arden expanded her academic foundation, while Jane Arden became a much-needed best friend, someone Mary could have fun with as young girls should during the all-important teenage years when youth seek their identities and test their independence. While the Ardens nurtured her intellect, they also provided Mary with an up-close view of what a loving, functioning family looked and felt like, vital for one who’d only experienced harshness and uncertainty at home.

Jane continued to be a role model for Mary over the course of the following decade. Like any young woman coming of age, Mary was in constant search of herself when she left Beverley. Her family would move two more times after Hoxton, first to Wales a year later, then back to London a year after that. In 1779, when Mary turned nineteen, she landed her first job, working as a lady’s companion to a wealthy woman in Bath. At this time she resumed her correspondence with Jane, who was working nearby as a teacher and later a governess. Perhaps it was by Jane’s example that Mary became a teacher and a headmistress at her own school for girls exactly ten years later in 1784.

In this brief look at the early letters between Mary and Jane Arden, it’s clear that Mary didn’t hesitate to expose her true feelings when writing to others. This habit continued. Between the first and last letter she would ever write in life, the same openness prevails, the same vulnerability, the same intense emotionality is present line by line. Her willingness, her need, even, to speak her mind, emboldened Mary to pen such groundbreaking work as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, where, as in her early letters, she combined reason with sensibility, leaning more toward reason but not letting go of sentiment. The rawness present in her youthful feelings would become the very things that would lead her to the truths that would one day make her famous.

Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft by N.J. Mastro is available in paperback and eBook at online bookstores, including Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, Bookbub, and Black Rose Writing.

This is such a wonderful article about a bright mind that doesn't get enough spotlight. While most focus on her "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman," I love that you took a more personal, intimate approach. I love reading the letters and journals of thinkers and writers because it offers a window that is often not found in their published works. And I am looking forward to purchasing Solitary Walker. The majority of what I read is non-fiction so I look forward to the changeup. Thank you for publishing such an enlightening piece!

Very interesting. Thank you. I didn't know much about Mary Wollstonecraft except that she was Mary Shelley's mother and a feminist. Now I want to know more about her and I think I will read your book.