Lives Like Loaded Guns: The Dickinson Family’s Feuds

One thing I speculated at the start of this journey was true: introverted Emily could see through facades. She was aware that Mabel’s presence wasn’t benign.

When I decided to make Emily Dickinson my subject for February, I pictured her in my mind as a shy poet hidden in her bedroom. There was no drama in this picture. There was no cause for conflict.

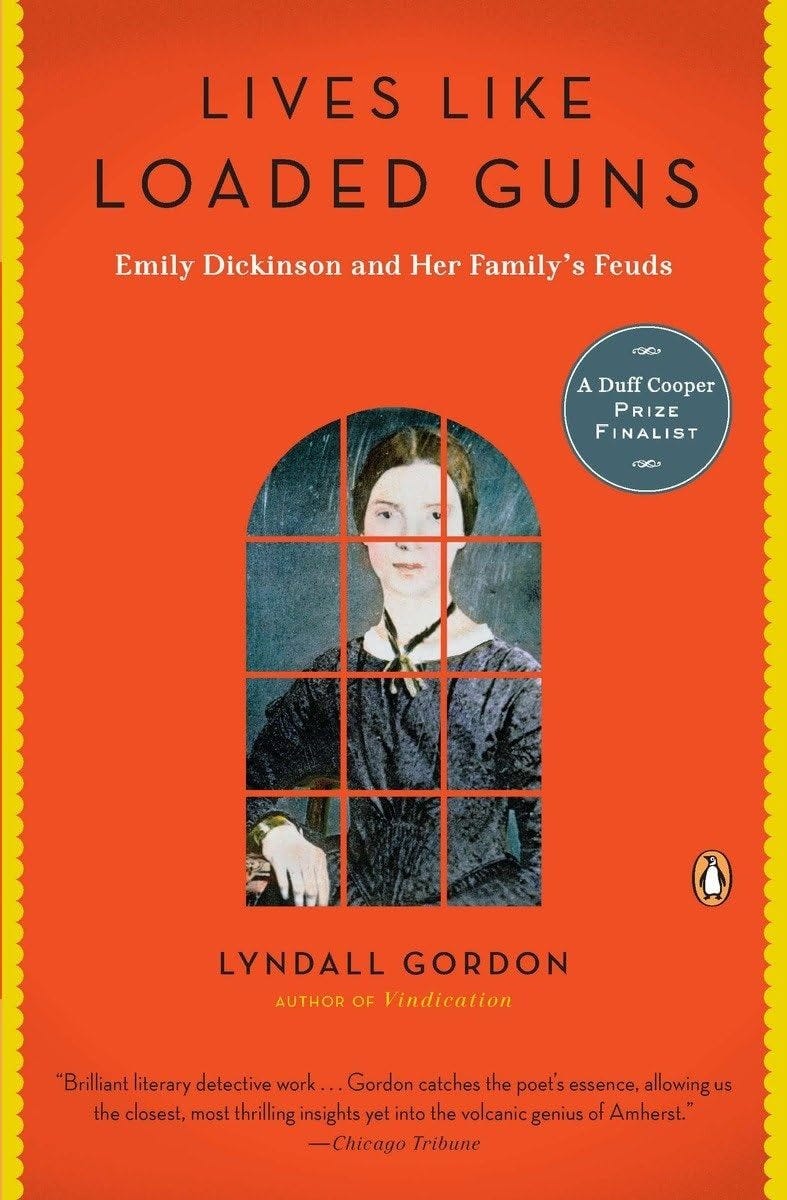

I have since finished Lives Like Loaded Guns by Lyndall Gordon. This biography is fresh on my mind—and it’s far from what I imagined.

One thing is certain: often, the images we have in mind of historical figures are fabricated.

Lives Like Loaded Guns begins with backstory:

In 1882 Austin Dickinson, in his fifties, fell in love with a young faculty wife. Twenty-six years before, Austin had married Susan Gilbert, the friend of his sister [Emily]. The Evergreens was built to accommodate the married pair next door to the family home on Main Street in the country town of Amherst in western Massachusetts.

This passage makes it sound like a simple matter of infidelity, but there was so much more. This book tells a complex story of envy, division, and anger that lasted longer than it should have.

Mrs. Mabel Todd

The ‘young faculty wife’ was Mrs. Mabel Todd, spouse of astronomer David Todd. Born Mabel Loomis, she grew up in Massachusetts, the only daughter of a mother and father who struggled financially. She did not enjoy being poor, and went on to live a life of ambition, determined to make it to the top, regardless of who she might hurt.

I always knew Emily Dickinson was introverted. Why did I assume she was also quiet and soft-spirited?

Gordon describes Emily Dickinson as reclusive, but not soft. She is choosy about who she interacts with. She communicates through poetry; if you peel back the layers of each piece, you realize the words are not mere rhyming fluff. These poems were often designed to be blows.

Emily Dickinson only lived to the age of fifty-five; the Dickinson family drama went on for much longer. It would evolve into a generational battle over the rights to her poetry, and it started when the Todds moved into the town of Amherst, near the Dickinsons’ home.

Emily never opened her heart to Mabel, but she communicated in her own way:

[Emily] sent Mrs Todd a few poems, possibly with a view to drawing her in. [Her sister] Lavinia said that [Emily] was ‘always watching for the rewarding person to come’. … Emily Dickinson did conduct her ties through handwritten copies of poems sent to those she admitted to friendship.

Was Emily admitting Mabel into friendship? Or was she trying to warn her away?

In Lives Like Loaded Guns, only a few chapters are dedicated to Emily Dickinson. I have a second book about her, and won’t feel that my search is over until I finish My Wars Are Laid Away in Books by Alfred Habegger.

Though not a book focused on the poet, Lives Like Loaded Guns paints in detail the situations shaping Emily’s poems. Perhaps the most important storyline is the matter of her brother Austin’s affair with Mrs. Todd.

According to Lyndall Gordon, Mabel and her husband moved to Massachusetts because he was pursuing work in astronomy. Mabel, at the time, was lost in an unhappy marriage.

Mr. David Todd didn’t think much of infidelity; he was involved in many affairs, a matter that Mabel did not know about until after they wed.

In the first years of their marriage, she endured an unfaithful husband who had no intention of changing. He even encouraged her to live a similar life. Eventually, Mabel gave in. This does not justify her decision to destroy a family, but I see the background.

Mabel was battered emotionally, blow after blow, until she wound up doing the very things that had first hurt her. Perhaps the difference between herself and her husband is that she took it too far.

The Mysterious Poet

By the 1870s, the existence of [Emily’s] poems in the Homestead had got about and Miss Emily had begun her long career as ‘the myth’. Curiosity grew about the recluse, the kind of talk that would captivate Mabel Todd when she arrived in Amherst.

Shortly after the move, Mabel Todd met the Dickinsons—and became obsessed. She was particularly obsessed with Susan, wife of Emily’s brother, Austin. Mabel harbored envy of Susan’s stable life and the respected position she held in the community.

Envy is not remarkable. Humans, by nature, often crave others’ success. It’s not an honorable emotion, but normal all the same. What’s remarkable is what Mabel was willing to do to write herself into the Dickinsons’ story.

She was unable to convince Austin to kill his wife (so that she could take Susan’s place), and she was unable to give him a child that would tie her forever with the family. She did not succeed, either, in convincing him to name her in his will instead of Susan.

These things did not discourage her; Mabel Todd was determined to become joined with this family, one way or another.

What did Emily think about Mabel Todd? She and Lavinia lived in the Homestead, next to Austin and Susan’s house. The homes were connected by a kitchen; aside from that, they were separate living spaces.

After beginning the affair with Mabel, Austin would take her almost every evening to the home where Emily and Lavinia lived. Since he paid their bills, they could not argue with him.

Emily’s disapproval was blunt. Mabel Todd never saw her in person. Their only interaction was through poems that Emily sent her, and the poems were not words of welcome.

Rather, they were riddled with jabs:

Can it be that Emily Dickinson was the first target of Mabel Todd’s takeover?

With writing ambitions of her own, [Mabel] was gripped by the poems Sue shared soon after Mabel’s arrival in Amherst. She began to put herself in the way of the recluse.

That first autumn of 1881, when Mabel was about to depart on a visit to Washington, she ventured to send the poet a message of farewell.

The reply was a rebuff to any delusion of intimacy Mabel might cultivate. ‘The parting of those that never met, shall it be delusion, or rather an unfolding of a snare whose fruitage is later?’

The word snare reads like a snap. Mabel was too clever not to catch on to the poet’s disapproval.

It was not enough to drive her away.

Carving a New History

Mabel Todd would pretend, long after Emily Dickinson’s death, that they had been friends. She assumed the authority to edit and publish several of Emily’s poems. Lavinia provided the original drafts, accepting the help because Mabel had a typewriter.

By crediting herself in the book as its editor, Mabel Todd succeeded in making herself a part of the Dickinsons, albeit indirectly. Since Emily Dickinson was dead, there was no one to rebuff her claim that they were friends.

All the same, it was a lie. Even when Mabel tried softening her with gifts, Emily did not bite:

Mabel sent [Emily] a painting of Indian Pipes. She would have gleaned from Austin or Vinnie that this was the poet’s favourite flower … The gift obliged Emily to thank her: ‘I know not how to thank you. We do not thank the Rainbow, although its Trophy is a snare.’ Again, a snare.

Austin Dickinson was not innocent. Even if he did refuse to change his will for Mabel, and (thankfully) did not kill his wife, he allowed an affair to destroy the peace in his home. He rejected his children when they expressed disapproval; he grew to hate his wife, using cruel words to tear her down.

Austin agreed to build the Todds a home next door. There would be no place for his family to escape from Mabel.

By the time Austin died, he had opened too many doors for her. The only way for them to escape would be moving away; since they did not, the Dickinson-Todd feud dragged on.

After Austin’s death, Mabel was determined to claim ownership of a meadow that grew between her house and the Homestead where Lavinia lived.

Emily was gone; now there was only Lavinia who, worn down by grief at the loss of her siblings, was desperate for comfort. Vulnerable, she became Mabel’s next target.

The Trial

Austin had not written in his will that Mabel would inherit the meadow. Mabel decided to arrange it, herself.

Mabel showed up at Lavinia’s door one day with a lawyer. This lawyer happened to be a Dickinson family friend. It was a carefully wrought plan: Mabel carried with her a contract that she had written up. The contract claimed that Austin had bequeathed this meadow to the Todds.

After the lawyer engaged Lavinia in nostalgic conversation, buttering her up, he brought up the contract. Lavinia, who trusted this lawyer, did not read the whole contract before signing it. She should have read it.

Days later, word spread that Lavinia had given a large chunk of land to Mrs. Todd. Susan Dickinson was furious; Lavinia’s niece and nephew were furious. The families soon faced one another in a bitter trial which, to Mabel’s great surprise, Lavinia won.

But how?

Their victory came when the Dickinsons’ hired servant, an Irishwoman named Martha, testified to witnessing, multiple times, Austin and Mabel’s affair. Her words were steady, backed with evidence.

At the time, no lawyer or judge was willing to risk their reputation by defending an adulteress. As a result, Lavinia won back the meadow she accidentally signed away:

On 3 April Judge Hopkins delivered his verdict. The deed Miss Dickinson had signed without understanding was held to be void. The court ordered Professor and Mrs Todd to return the land to Miss Dickinson. The judge also ordered the defendants to pay the costs of the trial: $49.55. Public opinion in Amherst on the whole favoured the judgment.

It would not end there. Mabel still had a good amount of Emily’s poems in her house. These poems be the means by which Todd would exact revenge. She would publish her own collections of poetry, as well as a biography of the poet. In this biography, she twisted the story so that it showed her in a favorable light, painting Susan as a poor wife and manipulator.

Emily Dickinson, who had seen through Mabel’s machinations from the start, became the means by which she forced herself into the picture. What ensued was a battle over copyright that would go on for generations, as Susan and Mabel’s daughters continued to battle.

In the End…

I found this book to be infuriating as well as intriguing. How long can a grudge last? Much of the time I wanted to knock sense into these people, particularly the daughters who perpetuated the feud.

One thing I speculated at the start of this journey was true: introverted Emily could see through facades. She was aware that Mabel’s presence wasn’t benign. Perhaps she guessed Mabel was trying to take Susan’s place.

Unfortunately, Emily died, and her work became a weapon by which Mabel carved herself into their family history. It was Mabel who, in her biography, crafted an image of Emily as a demure, gentle poet. It’s an inaccurate description: anyone who reads between the lines of the poems will see she was strong, and that her words were designed to pierce.

By softening the historical image of Emily, Mabel might have felt she was making herself stronger, vindicating herself from all of Emily’s snubs. Rather than take Susan’s place, she managed, in a sense, to take Emily’s. Until recently, no one challenged it.

This story is dizzying, difficult to believe—yet there are letters to back it up. It’s an example of why I always do research on authors’ backgrounds. Their stories are often more interesting than the books that they write.

No life is a fairytale; sometimes, years will crawl by before the truth comes out. In this case, the lie went on until after Mabel and Susan’s daughters had died.

My summary falls short of the drama described in the book. I could not give all of the details in less than 2,000 words. I highly recommend Lives Like Loaded Guns to anyone who is interested in Emily Dickinson and the motives behind her poetry.

I will begin reading the book by Habegger soon, and my posts about Emily will continue. For now, I’m reeling over the Todd-Dickinson battle.

I wonder if the poet was observing it all as it took place; if so, I wonder what she was thinking.

This is a bizarre post to publish on Valentine’s Day. I thank you for reading it all the same. Feel free to leave your comments; I love to hear thoughts and critique.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider leaving a tip here so I can buy more books for research! xx

Louisa May Alcott: “Little Women” Is Born

The Civil War began in 1861 and shook every person living in the country. It was the result of years of political tension, and its many battles resulted in appalling numbers of casualties.

It never ceases to amaze me the stories that lay beneath the surface of the commonly held perception. My master’s thesis was about Russian actor training and how censorship and translation created an entirely different identity for the same theory. There was also a bit of editorial and translational skullduggery…

I’ve so enjoyed these biographical essays on Emily Dickinson! So fascinating! Thanks for sharing Mariella!