Louisa May Alcott: What Were Her Sisters Like?

I read “Little Women” for the first time when I was a girl and wished I had such a group of sisters. I did not realize that their personalities were based on reality.

It’s the second Friday of November! I hope you’re enjoying Little Women; I am currently on Chapter 12, and the story is having the exact effect on me that I expected: it’s like a warm blanket on a chilly winter’s night. It is familiar and gentle, filled with messages of forgiveness and love.

In my previous post, I focused on the Alcott girls’ childhood. It was frightening and unstable, with their constant need to move due to their father’s inability to make rent.

The Alcotts spent their crucial younger years, that time when a child is beginning to develop a sense of self, in a constant state of poverty and homelessness. They were forced to borrow money from relatives. In time, even relatives became frustrated, retorting that Amos Bronson Alcott should toss his Transcendentalist philosophy and work to feed his own children.

Though it might seem a bleak introduction for a novel that’s overall happy, I thought it would put into perspective the brilliance of Little Women. It gives the impression of being a novel about being home; it focuses on a loving family, four daughters and their mother, in their comfortable house. In spite of their quarrels (what child does not quarrel with their siblings on occasion?), the girls know they can count on each other, that Mother is strong and always knows the answer, and she will always forgive them.

It seems odd, at times, that such warm qualities should appear in a novel written by an author who didn’t have home, safety, or stability at that age. The Alcotts’ situation became so dire that their mother fell into an understandable depression. One day, while in the mires of it, she told Louisa that she imagined her to one day be the one who would support their family.

Some might call it unkind to place such a burden on a child. All the same, Louisa would not disappoint her mother. She would go above and beyond what “Marmee” asked.

This week, I want to focus on something more light-hearted: the Alcott women.

Shortly after the Alcotts packed up and moved to Concord (because their mother, Abby May, had thrown her husband’s no-work policy to the wind and decided to find work), Bronson Alcott went on a speaking tour to promote the philosophy that kept his wife and daughters homeless and hungry during their tender years.

Enough about Bronson. This post is about the family he left behind—a wife and four daughters—who suddenly had to fend for themselves.

The older girls were teenagers at this time; the youngest, May, was scarcely more than a child. It’s a shame that, in biographies I’ve read, the five of them seemed more energetic without him, even if they did have to make ends meet themselves.

In my opinion, the most powerful biography we can find of the Alcott girls is Little Women itself. It follows the adventures of Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy March. Their sisterly bond is strong, even when they have disagreements.

I remember reading it when I was a girl and wishing I had such a group of sisters. I did not know, at the time, how their adventures were based on reality.

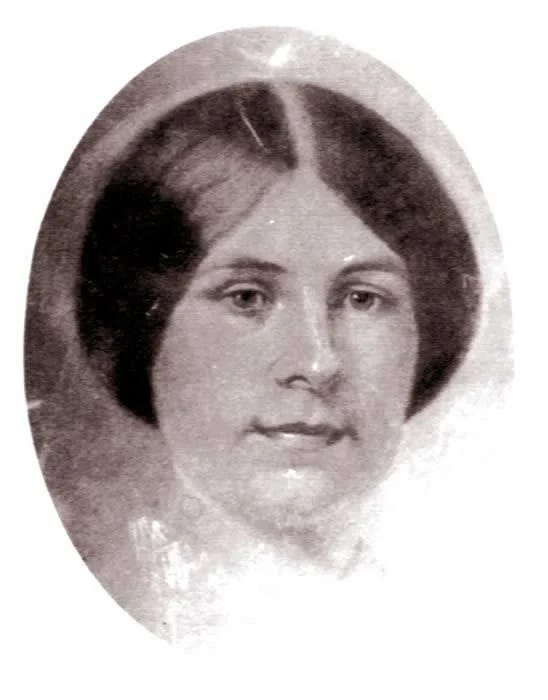

The daughters of Amos Bronson Alcott and Abby May Alcott were Anna (March 16, 1831-July 17, 1893), who was the inspiration for Meg March; Louisa (November 29, 1832-March 6, 1888), who wrote herself into the story as Jo March; Elizabeth (June 24, 1835-March 14, 1858), whose tragically short life inspired Beth; and Abigail, known as May by her family (July 26, 1840-December 29, 1879), who graced the novel as Amy.

The Alcott sisters’ adventures together began in their earlier years, while they were enduring poverty. Creative as children are, they found ways to cope; in 1849, they started a family newspaper called The Olive Branch. Everybody contributed; these contributions ranged from poetry to plays to make-believe advertisements.

It was inspired by Dickens’ popular book, The Pickwick Papers. Each sister took on an alias from Pickwick. Louisa used the pen name of Augustus Snodgrass; Anna was Samuel Pickwick; Lizzie was Tracey Tubman; May was Nathaniel Winkle. A chapter in Little Women is dedicated to this memory: Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy also have a “homemade newspaper.” The chapter features poetry, stories and articles. It is a clever chapter; we can tell, by each entry, which character is supposed to have written it. I finished it wishing for more.

Louisa drew ideas for her stories from real life. She often used people she knew as the basis for her characters. Though she changed names and other identifying factors, the reader who is aware of her life story can often work out who inspired each character.

Over the course of her life, she had no shortage of people and places from which to spin a story. Her many occupations helped, as well: she took on a variety of roles, from housemaid to theatre actress to teacher. She volunteered as a nurse during the Civil War, which inspired her to write the book Hospital Sketches.

She became acquainted with many influential authors and public figures—initially due to her father’s connections. In time, however, they were flocking to know her.

Louisa lived during a time when the world was undergoing great changes. I believe that, with her carefully crafted tales, she contributed to them. A well-written story is more than words on a page; if penned with sufficient passion, it will make a change. If it does not change the world, it can change a heart, or change someone’s decision, providing hope where it was previously absent.

Louisa’s warmest stories were those that “featured” her sisters. Though this is just an opinion, it seems to me that Little Women was an attempt to make up for their colorless younger years.

In the novel, she spins tales of an alternate childhood where life was not so difficult—or at least, their difficulties were different by nature. In refusing to work, Bronson Alcott forced an already overworked mother to change cities in search of employment. After Abby became bread-winner as well as a mother of four, he traipsed off on a tour to promote his philosophy.

Compare Bronson’s absence to the situation in Little Women, where the reason why Father left is simpler and nobler: he has gone off to fight in the war.

Anna and Louisa, being the oldest, sought jobs of their own in order to help their mother. Lizzie seems to have spent most of her time with the housework, while May went to school, where she took an interest in art and illustration. She would later go on to be a painter; unfortunately, the success of Louisa’s novels overshadowed May’s achievements. This excellent article sheds more light on May’s life as an artist.

Little Women was not the first story Louisa wrote that “featured” her sisters. During the early Concord years, she published a piece in a periodical called The Sisters’ Trial, which I will speak of more later in the article. The Sisters’ Trial reads like wishful thinking. Perhaps Louisa the budding author already knew what she desired for their future. She was optimistic about what she and her sisters could become if given the opportunity.

After the Alcotts moved to Concord, their mother began to work. Her job resembled what is now referred to as ‘social work’. She would routinely visit poor neighborhoods, where she witnessed the suffering of families worse off than the Alcotts themselves.

Like Marmee in Little Women, Abby Alcott had a natural inclination to help those in need. She taught her daughters to do the same; the four of them were encouraged to leave the world a better place than they found it.

Though Bronson believed himself to be making the world a better place, his wife’s strategy was different. Abby knocked at the doors of struggling families in Concord, exposing herself to danger and illness in order to offer relief and make money.

Meanwhile, her husband continued his promotional “tour” in the name of Trancendentalism. He allegedly sent his family a check at the start of the tour, but it was not enough to keep them comfortable and fed. It is also said that he engaged in a series of “flirtations” with women from his audiences.

Did Abby suspect his infidelity? If so, she wasn’t alone. She had her daughters to provide emotional and financial support.

Her eldest, Anna, began work as a teacher. In time, she became a natural at it; she would be hired as a tutor for children in various households. Louisa also attempted to teach, but her personality was different; she struggled to manage a class.

Read more about Anna Alcott Pratt in this excellent post!

Acknowledging that her calling was not in the classroom, Louisa moved on. She juggled odd-jobs which included sewing and cleaning. She also took up (of course) writing. In Concord she began pitching short stories to periodicals, including The Sisters’ Trial. It was released in the Saturday Evening Post issue for January of 1856.

Louisa earned $6 for this story. She published it under the rather conspicuous pseudonym of “M.L.A.” — I can picture Louisa laughing as she scrambled those letters on the page.

Not all was peaceful in the Alcott household, however.

Elizabeth, or Lizzie, is the most mysterious Alcott sister. I’ve yet to find much to describe her personality—at least, not in the way that Louisa or Anna were painted by their father.

Lizzie appears to have been a homebody, helping her mother with chores in the house. Tragically, it took one venture out for the young lady to fall ill. She contracted scarlet fever at the age of twenty-two (unlike Beth in the novel, who becomes ill as a child). Lizzie caught the illness while helping her mother tend to poor families.

Something I was dying to know as I researched Lizzie was, Is Beth’s piano based on reality? To my delight, the answer is yes! She was gifted a piano, though not from a neighbor. It was given by a friend that Anna and Louisa knew from the theatre scene.

Perhaps Lizzie spent her days of illness at the keys; music might have been her consolation as she became increasingly ill. This very same piano sits underneath her portrait at Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts; it’s the same house in which Louisa wrote Little Women.

She appears to have suffered from some other condition, aside from the scarlet fever that killed her.

Her mother wrote to Bronson in a letter:

“It seems as if there had been some collapse of the brain,” Abby wrote to Bronson in Cincinnati in mid-November. “At times she seems immovable—almost senseless. Louisa and I both relieve her of all her work… There is a great struggle going on in her mind about something.”

— Louisa May Alcott: The Woman behind Little Women by Harriet Reisen

Later, Abby speculates that Lizzie’s illness was caused by depression due to their situation:

“I think Anna and Lizzie are a good deal oppressed with this [economic] uncertainty.” They were not as well equipped to endure or cure it as Louisa was. “Louisa feels stronger and braver—to meet or to bear whatever destiny may have in store for us… The other girls are not so firm in health and there is more dependent feeling on their parents.”

— Louisa May Alcott: The Woman behind Little Women by Harriet Reisen

Whatever the cause for her frailty, Lizzie succumbed to scarlet fever on March 14, 1858, leaving a deep scar in the hearts of her family.

However, Lizzie is not truly dead. By writing her into Little Women as the sweetest of the four, Louisa invites the rest of us to remember Lizzie Alcott—and perhaps to grieve for her, too, like we often grieve for a fictional character.

Louisa used to tell a story about the cold winter night when Bronson returned from his tour.

“Did they give you money?” little May asked, and he pulled a dollar out of his pocket-book, saying with a smile, “Only that!” (We can all sense the girls’ disappointment here). His wife, in spite of all that she’d had to do to keep their children afloat during his absence, embraced him.

“I call that doing very well,” Abby told her husband. “Since you are safely home, dear, we don’t ask anything more.”

Whether or not the story is true—whether he made more than just a dollar—his tour did not change the Alcott family’s fortune. Only later would he find more enthusiastic readers for his work—because of his association with Louisa, the child he had once characterized as wicked.

Alas—my attempt to write a more cheerful blog post has dipped to the wistful state of grief one feels when a person dies who needn’t have. As I keep saying, an author’s personal story is often more interesting than the novels they write.

Next week, my post might be even bleaker—because I’m going to write about Louisa’s time as a volunteer nurse during the Civil War. I’m going to skim her book Hospital Sketches and find out how the sights of dead or suffering soldiers made her into a stronger woman…until she became ill herself and was forced to return home.

As always, feel free to comment with any corrections, comments, critique, or ideas; I am eager to improve at article-writing, and can only do so with your input.

To join our Little Women read-along on Facebook, click here! There’s still plenty of time to catch up.

— Mariella

Louisa May Alcott & the Struggling Roots of Little Women

“It’s so dreadful to be poor,” sighed Meg, looking down at her old dress.

"A well-written story is more than words on a page; if penned with sufficient passion, it will make a change. If it does not change the world, it can change a heart, or change someone’s decision, providing hope where it was previously absent."

I appreciate this sentiment - it's a good part of the reason I enjoy reading so much. Providing hope is huge!

I enjoyed reading this, and it further 'proves' a little theory I have about people who have veins of tragedy within their lives having some beautiful gift - a talent - that they in turn share with the world which can bring a sort of redemption to their suffering. (I'm still working on just how to articulate that so I hope it makes sense.)

Very interesting! It makes a lot of sense that she would reimagine her own life in another, brighter light.