Ten Fictional Female Detectives From Long Before Miss Marple

Long before Jane Marple made her appearance in 1927, other female detectives were gracing the pages of English and American mystery stories.

When most people think of female detectives in fiction, the first name that comes to mind is Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple, the white-haired little old lady from St. Mary Mead whose fluffy appearance and scatterbrained manner hide an uncanny crime-solving ability. What they may not know is that while Miss Marple may be the most famous, she certainly wasn’t the first. Long before Jane Marple made her first appearance in the 1927 short story “The Tuesday Night Club,” many other fictional female detectives—young, old, beautiful, plain, lively, or nondescript—were already gracing the pages of both English and American mystery stories. In fact, the earliest female detectives in fiction made their appearance over half a century before Miss Marple first appeared in print.

Andrew Forrester: “Miss Gladden” (1864)

“Miss Gladden” may not even be her real name. She calls it “the name I most frequently use in my business.” The police officers who know her refer to her simply as “G.” Compared to later fictional detectives, as a character she is almost completely anonymous by choice. The reader knows nothing of her appearance, personality, or background, and within the stories she narrates, her acquaintances have no idea she is a detective.

The Female Detective by Andrew Forrester (a pseudonym for James Redding Ware), published in 1864, and another book titled Revelations of a Lady Detective published anonymously the same year were early outliers in the detective genre, in an era when detectives both male and female were considered less than respectable. “I know well that my trade is despised,” says “G.”, attributing it to the fact that “there is something peculiarly objectionable about the spy.” While insisting that her profession is necessary, she seems to half despise it herself, almost pitying or sympathizing with the criminals she makes it her business to track down. The seven stories in Forrester’s book are an odd mix, only three being cases in which “G.” plays an active role, the others being represented as manuscripts shared with her or incidents told to her, some of them unsolved.

Catherine Louisa Pirkis: Loveday Brooke (1894)

By the time the character of Loveday Brooke appeared in print, detective stories were becoming increasingly popular with the public, even though the profession of detective itself was still seen as not quite genteel. Loveday, a young woman of unspecified but respectable background, is said to have “cut her[self] off sharply from her former associates and her position in society” by choosing to go to work as a detective.

Compared to other, more romantic female detectives of a decade or so later, Loveday is all business. A woman in her thirties, unremarkable in appearance, she works for a thriving private detective agency and has the full respect of her male employer, though they occasionally wrangle over theories like all good detectives do.

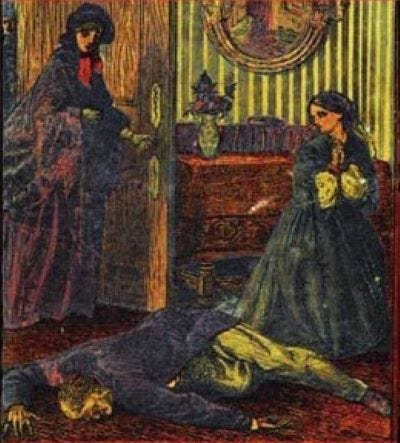

Anna Katharine Green: Amelia Butterworth (1897)

“I am not an inquisitive woman,” begins Miss Amelia Butterworth’s narration in That Affair Next Door; but when a sensational murder takes place in the house next door to hers, the genteel spinster just happens to be looking out the window to witness something important—and to be on hand when the body is discovered—and before long is assisting the detective in charge of the case! Miss Butterworth, with her prim insistence that she has no curiosity and acts merely from a sense of justice—all while doggedly pursuing clues in a “fever of investigation”—is a real character, one of the most enjoyable personalities among the early ladies of detective fiction.

Anna Katharine Green, one of the first American mystery authors, and officially the second American woman to publish a mystery novel with her 1878 debut The Leavenworth Case (the first was Seeley Regester with The Dead Letter in 1866), is often credited with inventing the elderly spinster detective with the character of the entertaining Miss Butterworth, who would go on to appear in two more of Green’s novels, Lost Man’s Lane and The Circular Study.

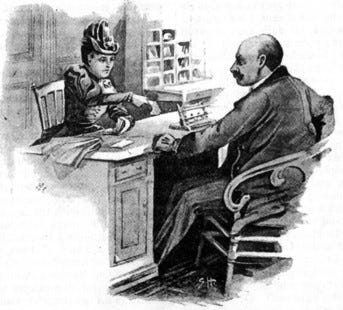

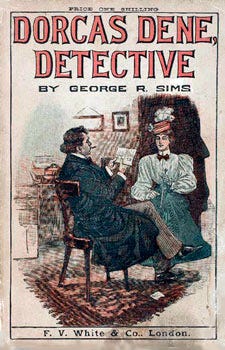

George Robert Sims: Dorcas Dene (1897)

Dorcas Dene, a former actress, turns private detective in order to support her blind husband, using her skills in acting and costuming to assume effective disguises as she pursues her investigations. Dorcas enjoys a happy, domestic private life, discussing her cases—classic late-Victorian affairs of missing heirs, secret marriages, and pawned jewels—by the fireside with her husband, her mother, and the theatrical agent friend who narrates and chronicles her adventures (not to mention her loyal pet bulldog).

Matthias McDonnell Bodkin: Dora Myrl (1900)

Dora Myrl is quite the epitome of an accomplished turn-of-the-century young lady. Though described as a “dainty little lady” who looks like a “schoolgirl,” her qualifications are staggering—in her first appearance in print she describes herself as Cambridge-educated, qualified as a medical doctor, and having worked as a telegrapher, a telephone girl, and a journalist before settling on becoming a private detective!

Irish author Matthias McDonnell Bodkin (you couldn’t make up a name like that) eventually created one of the first literary detective families, marrying Dora to another of his fictional creations, detective Paul Beck, in 1909, and subsequently featuring their son Paul Jr. in a book of his own.

Emmuska Orczy: Lady Molly Robertson-Kirk (1910)

Baroness Emmuska Orczy, most famous for The Scarlet Pimpernel, created another character who leads a kind of double life in Lady Molly, a professional lady detective with a mysterious background. She is rumored to have been born an aristocrat, and manages to maintain her ties to high society while serving as the head of Scotland Yard’s “Female Department”—a wholly fictional department at the time: in reality Scotland Yard did not appoint its first female officers and investigators until a decade later.

Later on we learn the full truth of Lady Molly’s background as well as her personal reason for joining the force and cultivating her detective skills. The narrator of her stories is Mary Granard, sometimes her maid, sometimes her secretary, always her assistant and admiring friend. Lady Molly’s particular specialty seems to be guessing the correct solution of a case early on and then coming up with creative ways to trick a confession out of the guilty party.

Richard Marsh: Judith Lee (1912)

Judith Lee is a detective not so much by choice as by strange circumstances that catapult her into it. Raised by deaf parents, she is an expert lip-reader, and repeatedly “overhears”—or rather sees—cryptic conversations that put her into danger or prompt her to try and prevent or solve a crime. Her official profession is a teacher for the deaf and dumb, but once her unusual skills become known, she is sometimes asked to put them to detective use—and also becomes the target of criminals who regard her as a dangerous threat to their activities.

Geraldine Bonner: Molly Morgenthau (1914)

A spunky, appealing heroine, New York City-bred Molly Morgenthau made her debut in the The Girl at Central, where she is working as the switchboard operator in a small town when a beautiful heiress is brutally and mysteriously murdered. Molly, who has a bit of a crush on the chief suspect, puts her telephone skills to use to ferret out evidence, and strikes up a friendship with a cheeky young reporter working the case on his own account.

Either author Geraldine Bonner or her readers were evidently fond enough of Molly for Bonner to bring her back in a supporting role in two subsequent novels, The Black Eagle Mystery and Miss Maitland, Private Secretary—now happily married, but still happy to do a spot of unofficial detective work to oblige a friend.

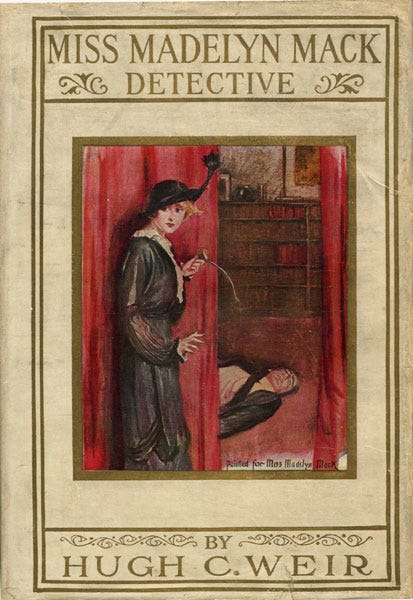

Hugh Cosgro Weir: Madelyn Mack (1914)

Madelyn Mack comes across as a young—and, of course, beautiful—female, American edition of the Sherlock Holmes style of detective: extraordinary intelligence, sensational notoriety, luxurious lifestyle (a country house on the Hudson River, and her own car and chauffeur), and eccentric habits (she hires famous musicians to make records of classical music for her, and her newspaper-woman Watson even chides her about her use of the “stimulant” of chewing “cola berries” when she is on a case).

Unlike some other lady detectives of the time, who operate from home and mostly help clients referred to them personally, Miss Mack is said to have a New York City office and a staff of male operatives, though they make no further appearance after the first story. And carrying the Sherlock Holmes similarity one step further, it’s her sidekick Nora who is given a romance, ultimately marrying a (successfully cleared!) suspect at the end of the final story.

Anna Katharine Green: Violet Strange (1915)

Anna Katharine Green’s second lady-detective creation is a young New York debutante—outwardly a frivolous social butterfly, but secretly employed as a specialized and expensive private detective. Violet chiefly handles cases involving women and high society—like other female detectives, she has the advantage of being able to go where the police or male detectives can’t: being accepted as a guest into upper-class households, gaining the confidence of female suspects, and handling delicate family secrets and scandals.

Like Orczy’s Lady Molly, Violet has a secret motive of her own for becoming a detective. Unlike with Lady Molly, however, the reader is made aware that such a motive exists from the very beginning, creating an additional thread of mystery that runs through the series of short stories: why does a girl brought up to wealth and luxury pursue such an unusual career merely for the high fees? Her secret reason is ultimately revealed in the final story.

About the Author

Elisabeth Grace Foley—Elisabeth spelled with an S—writes historical fiction fueled by her love of the American West, Golden Age mystery fiction, and classic literature (including the Mrs. Meade Mysteries, a series of short cozy mysteries featuring a lady detective in Edwardian-era Colorado). She blogs about literature and history and posts occasional short fiction at The Second Sentence. To learn more about her books, click here.

Louisa May Alcott: What Were Her Sisters Like?

It’s the second Friday of November! I hope you’re enjoying Little Women; I am currently on Chapter 12, and the story is having the exact effect on me that I expected: it’s like a warm blanket on a chilly winter’s night. It is familiar and gentle, filled with messages of forgiveness and love.

I had no idea there were so many female detective characters in this earlier era. Very interesting.

This is great! I've actually just been reading some Anna Katherine Green, will have to try some of these others