The Illusion of Jane Austen’s Death

Jane Austen was taken by a mysterious illness, not knowing how loved she would be centuries later.

January is nearing an end.

When I sat down to write this final Jane Austen-themed post for the month, I was in the living room. It was a bright afternoon, but very chilly.

I stared out the window at sunlight that was deceptive. It looked like it might be warm enough to step outside, but that was the last thing I wanted to do. It’s been freezing but with no snow, so there wasn’t even photography to entice me.

The point of this introduction is a depressing fact: not everything is as it seems. Often, what we see is only an illusion.

Artists thrive on the power of illusion. In much of art, illusions are created on purpose. In literature, authors write characters that do not die. They grip readers long after their author’s heart stops beating.

‘Fencing with Words’

A cynic can say that words on a page are but symbols. To a book lover, they’re so much more! If approached with an open mind, those symbols bring to life a Marianne Dashwood or Mr. Darcy.

The characters I’m thinking about were created by Miss Jane Austen, who observed the world into which she had been born. Into her stories she wrote what I heard someone call ‘fencing with words’.

That clever phrase helped me understand why I often feel, when reading Jane’s dialogue, as if I was reading a battle scene.

Kill them with kindness, the saying goes. Jane takes it several steps further; often, her characters aren’t trying to be kind, yet they are still being civil—aren’t trying to be likable, and are liked even less by the reader by the end of the chapter.

Take, for example, almost every exchange between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet, such as this:

‘Mr. Bennet, how can you abuse your own children in such a way! You take delight in vexing me. You have no compassion of my poor nerves.’

‘You mistake me, my dear. I have a high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these twenty years at least.’

‘Ah! You do not know what I suffer.’

‘But I hope you will get over it, and live to see many young men of four thousand a year come into the neighbourhood.’

‘Oh, my poor nerves!’ I couldn’t help sharing this passage, though—I love the first chapter of Pride and Prejudice so much!

Deceptive Sunlight

As I took in that deceptive, bright sunlight, I was already feeling melancholy about the nature of this post.

I found myself wondering if, when she was not feeling well, Jane Austen did the same thing. Did she ever stare out of a window during the final days of her life, pondering the deceptive hope of a sunbeam?

Jane Austen was taken by a mysterious illness, not knowing how loved she would be centuries later. She left in her wake an unfinished novel, a heartbroken family, and characters that would outlive her.

By the time she felt the first symptoms of illness, Jane had begun to make an income from her novels. She was not paid enough to feel secure, and speaking from my privileged place in the future, I know she wasn’t paid half as much as she deserved.

Who would have thought that those witty, fencing with words novels would still be popular today? Who could have told her that there would be so many films, spinoffs, and works of fan-fiction? She wouldn’t have believed it, I wager.

If we’re honest, it might have made her uncomfortable. Jane doesn’t seem to have had a desire to be seen. ‘Aunt Jane’ was happy to make magic in the comfort of her room, wherever she might be living (for, as I discussed in this post, she never had a home of her own).

She took her secrets to the grave, and her sister Cassandra did the same.

Jane Austen & Beth March

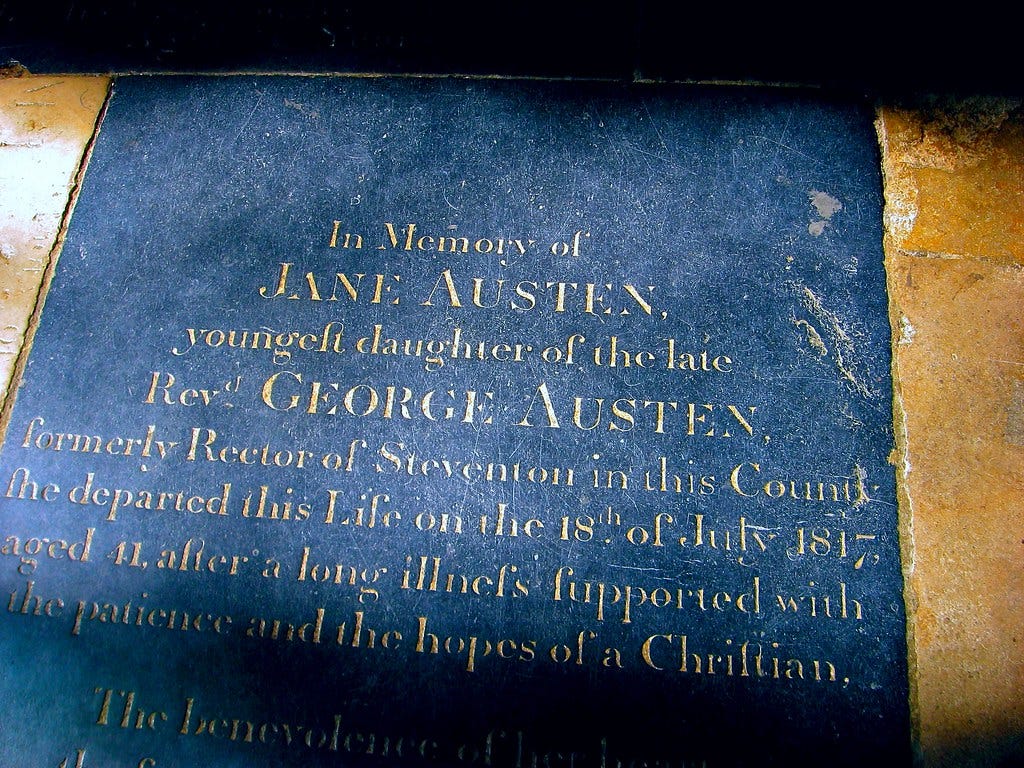

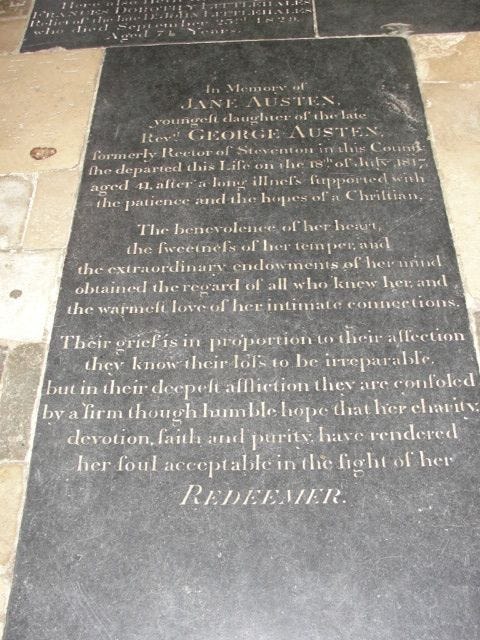

Jane Austen died on July 18, 1817 at the age of forty-one. She had been ill for a long time, and the cause of her death continues to be debated.

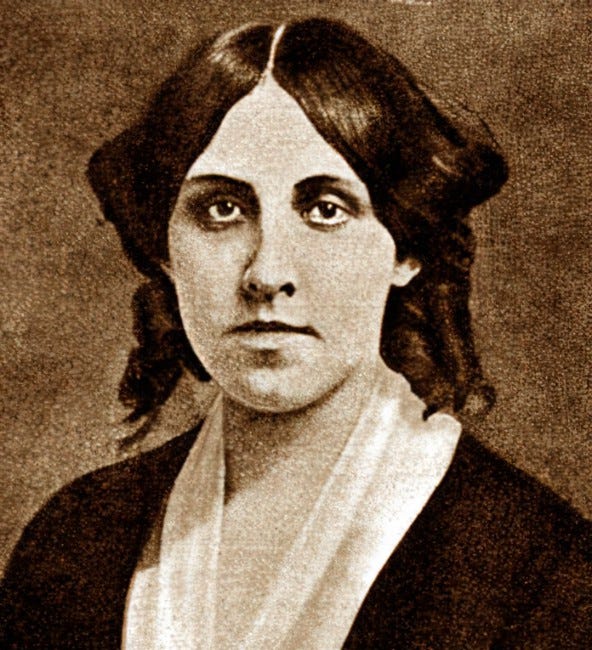

Lucy Worsley did an excellent job of chronicling Jane’s final weeks in Jane Austen at Home. In this humble blog, I feel an urge to share my own musings, but they branch out to a different era—and another author.

In Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (who had many beliefs in common with Jane), Alcott writes that, once the illness was at its strongest, Beth sewed ‘until the needle became too heavy.’

Here is the quote:

It was well for all that this peaceful time was given them as preparation for the sad hours to come, for by-and-by, Beth said the needle was 'so heavy', and put it down forever. Talking wearied her, faces troubled her, pain claimed her for its own, and her tranquil spirit was sorrowfully perturbed by the ills that vexed her feeble flesh.

— Little Women, Louisa May Alcott, Chapter 40 (emphasis mine)

Perhaps I am grasping at straws, creating parallels between Jane Austen and a fictional character (though the truth is that Beth wasn’t really fictional; she was inspired by Alcott’s sister, Lizzie. Learn more about that here!)

Hear me out, though—I feel far too clever, having been hit by this reverie. Both Jane and Beth were, for the most part, quiet homebodies. Both were content to serve their families. Jane was attached to her older sister, Cassandra; Beth is written as being closest with her older sister, Jo—so much so that, in her dying days, she feels stronger when Jo is near.

The difference is that Jane traveled to different cities; Beth is not written as a character who leaves the house often, and when she does, it’s seldom far. She visits the poor family that we meet in chapter one, and she visits Laurie’s uncle to play at the piano, but those places are both a walk away.

Jane traveled, but seldom alone. When she did visit places alone, she always returned to her sister. To her, home was where Cassandra happened to be.

Perhaps we can say, with heavy hearts, that Jane continued writing Sanditon until the pen became too heavy.

Sanditon is the novel she didn’t finish; such novels haunt me. Dickens has a similar case, an unfinished book, in The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

How did they mean for these stories to end?

Symptoms & Sofas

What were Jane’s symptoms?

Worsley writes that the trouble began with her eyesight. There were other, puzzling things as well; in 1813, Jane’s niece, Fanny Knight, wrote in her journal that her aunt was suffering from ‘a bad face ache’.

Fanny’s sister Lizzy recalled that Jane often walked ‘with her head a little to the side, a very small cushion pressed against her cheek, if she were suffering from face-ache, as she not unfrequently did in later life’.

From the spring of 1816, Jane begins to write in her letters of terrible back pain, ‘pain in my knee now & then’, as well as a persistent fever. One niece remembered how, after dinner at Chawton Cottage, Aunt Jane would often lie down, but not upon a sofa.

Worsley writes:

Instead, she would line up ‘3 chairs’ as a makeshift piece of furniture, which ‘never looked comfortable’. Jane called it ‘her sofa’, and preferred it to the real one. Her reason was that she wanted to leave the actual sofa free for her mother. She wanted Mrs Austen to be able to lie down ‘whenever she felt inclined.’

This passage hints at the strained relationship Jane seems to have had with her mother. It’s a matter I meant to write about in January. There are many things about Jane’s life that casual readers would find surprising.

Mrs Austen was, apparently, a difficult parent to manage with. Some have suggested that the many irritating, hysterical mothers in her novels were inspired by her own.

It’s a topic I plan to write about, after a bit more research. However, this post is about Jane’s illness.

Modern Dignosis

Literary scholars have scoured Jane’s letters, as well as her family’s, hoping to figure out what it was that ended this talented woman’s life. There are a few theories, based on what little can be gleaned.

In 1964, a physician called Sir Zachary Cope studied the available evidence and diagnosed Jane with Addison’s disease. It’s is a disorder of the two small adrenal glands above the kidneys. Symptoms include fainting, weakness, and cramps.

Almost at once, however, other physicians disagreed with Cope’s conclusion.

They suggested that Jane was actually suffering from Hodgkin’s disease, a cancer of the white blood cells. It is a deceptive cancer with a cycle of illness and improvement. The disorder builds over a few weeks to high fever and night sweats; these then fade, leaving the victim feeling better but extremely weak.

In other words, the sufferer is duped into thinking they have recovered—when the truth is that their time is running out.

Jane and Cassandra visited a spa called Cheltenham together in 1816. Cheltenham was frequented by the sick, believed to be a place of healing. It did not seem to do Jane any good.

On their journey back, they stopped at the house of some old friends, the Fowle family.

The Fowles could see Jane’s discomfort; they ‘received an impression that Jane’s health was failing—altho’ they did not know of any particular malady.’ In hindsight, they began to speculate Jane was visiting old friends and familiar sites ‘as if she were taking leave [of them]’.

In September of that year, Jane concluded that her discomfort was linked to a lack of rest. She believed that all of it, including the back and face pain, was a result of what we call stress today.

Jane wrote to Cassandra, who was once more in Cheltenham, ‘My Back has given me scarcely any pain for many days. — I have an idea that agitation does it as much harm as fatigue, & that I was ill at the time of your going, from the very circumstance of your going.’

In this excerpt, we see once more the sisters’ strong attachment to one another.

What Remains, Then?

Literature is an adventure. We find a thrill, not only in reading the books that shape our society, but also by digging into the lives of the authors who wrote these books.

History is one great puzzle. It will always provide questions that we readers would do anything to find answers to. This includes scouring Jane’s letters for symptoms to diagnose her, or deep-reading Louisa May Alcott’s journal to figure out why she and Laddie ‘couldn’t be.’

Human beings die. The artists and authors behind immortal works cannot live forever; we all eventually become dust. What we create, and how it impacts others, is our legacy. We will be remembered by how we improve our world, using the time we’re given.

Jane Austen did not live forever in a physical form, but her books did. Her characters did. The witty conversations and quotes that many can recite from heart, did. We can be grateful that, whenever we need advice from Aunt Jane, we can reach for her books.

If you are a creator, an artist, or simply a reader, remember—you don’t know how your achievements will change the future. Van Gogh was not successful in life; now his work is admired by all.

Put forth your best, give the world all that you’ve got. There is never too much art; there are never too many books.

We still don’t know what Jane Austen died of. To be honest, in my heart, she’s not truly dead; she’s very much alive in the hearts of readers.

Thank you for exploring the life of Jane Austen with me! There is still so much about her to learn; you can be sure that a couple more posts will be published about her in the very near future.

Join me in February as I explore the story and poems of Emily Dickinson. She’s calling me, so she must naturally be our next guest at the Tearoom!

Louisa May Alcott’s “Polish Boy”

I hope you enjoy my article about Louisa May Alcott and the man who most likely inspired Laurie in Little Women! This article was originally published in the excellent newsletter Pens and Poison by Liza Libes.

Love a deep dive on Jane Austen! And I love your ending about the importance of putting your art out there - thank goodness jane Austen did before her death!

As always, there is so much research and ‘heart’ in your article 💛 This is what I love about your posts—a personal touch! :) The writing is simple yet lyrical. Well done!