Louisa May Alcott’s First War

At the hospital, Louisa rolled up her sleeves, marking herself like a page with the blood and tears of the dying. Ever the author, she helped wounded heroes write their final letters.

Write what you know is a nugget of advice commonly given to authors. These words are repeated so often that they risk losing significance. They often become little more than white noise as an author struggles through the writing process.

There are instances when a writer has indeed written what they knew. Louisa May Alcott’s book Hospital Sketches is one such example.

Though written during a dark time (the Civil War), it’s not without humor. The book follows a protagonist called Nurse Tribulation Periwinkle, whose adventures ‘on duty’ are very Louisa-like. The book describes her frustration at not being taken seriously for being a woman, recounting heated exchanges with know-it-all surgeons.

Even with its lighthearted moments, Hospital Sketches captures the feel of a hospital full of wounded men. Perhaps Louisa added humor because the times were so dark that she knew her audience needed to smile at something.

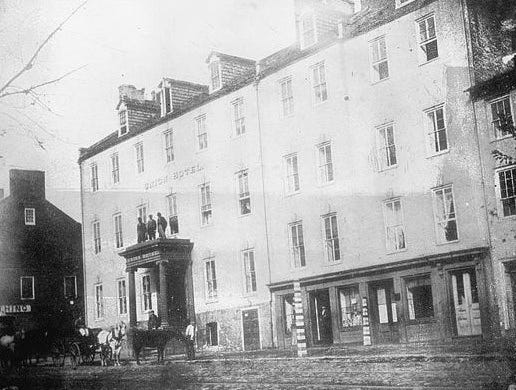

However, Louisa’s personal recollections take on a different tone. Away from the spotlight, she recounted her stories verbally, but also wrote letters using grim realism. She could never forget the devastating things she saw at Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, Washington DC.

No decent person likes war or wants one to happen. However, when political tensions over abolition broke into battle in 1861, many supporters of the cause felt a sense that their desire for equality would see progress.

They could not imagine the scale of the carnage this progress would leave in its wake. They might not have been so jubilant, if they’d had an inkling of the losses our country would suffer. At the start of this dark chapter, they only wished for a world where all humans shared the same rights.

Among these abolitionists were the Alcott family. At the time, Louisa lived with her parents and sisters in Concord, where $4,400 was raised by the community to send their men on trains to fight for equality.

Louisa watched the town’s preparations wistfully. She confided to her journal that she wished she’d been born a boy, because she longed to see a war fought. She held a notion that it would be ‘romantic.’

This notion of hers would not last long.

After the local men left for war, Louisa made a decision. If she was not able to fight as a soldier because of her gender, she would help those who could. Set on volunteering as a nurse, she began to do research on gunshot wounds.

“I want to do something splendid...something heroic or wonderful that won’t be forgotten after I’m dead. I don’t know what, but I’m on the watch for it and mean to astonish you all someday.” —Louisa May Alcott, Little Women

Louisa’s choice might also have been motivated by her unhappy work situation. Since the Alcotts were always in need of money, she had accepted an offer from Elizabeth Peabody to become a kindergarten teacher.

It hadn’t been the first time she tried and failed to be content in a classroom. Louisa accepted Peabody’s offer for her family’s sake, but time had not changed her personality. She did not have the patience to work with students.

This desperation to leave the classroom, paired with a romantic notion of war, moved her to volunteer as a nurse at Georgetown’s Union Station Hospital in Washington, D.C. I imagine that, as she signed her name, she had no way of guessing the scale of suffering that she would witness.

It would be the first time Louisa went so far from home. She was at last ‘spreading her wings’. Having always been close with her family, especially her mother and sisters, she became overwhelmed. As they helped her to prepare, they all knew that—if she returned from the hospital unharmed—things would not be the same.

On that December day in 1862, as her mother and sister helped her into a coach that would take her to the station, an emotional Louisa burst into tears.

However, she soldiered on, remembering that the men had made greater sacrifices.

Louisa May Alcott steeled herself. She then boarded the train that would sweep her to a place where she would see the reality of war—and quickly lose her impression of it being romantic.

Louisa would see men with amputated limbs and broken minds. She would watch soldiers show signs of life one moment, only to die within seconds. Her parents were fighters for social justice, but their struggle took the form of verbal advocacy. She had chosen a different path.

She’d placed herself in the midst of the chaos, no longer penning articles from the comfort of home. At the hospital, she rolled up her sleeves, marking herself like a page with the blood and tears of the dying. She helped wounded heroes write their final letters. She washed their weak bodies and kept them company, amusing them with her theatrical skills, telling them stories.

Later, Bronson Alcott would find himself affected after witnessing the suffering soldiers who had fought to support his cause. Neither he nor his wife had ever imagined such carnage.

“[A] hospital is a rough school, its lessons are both stern and salutary; and the humblest of pupils there in proportion to his faithfulness learns a deep faith in God and in himself.”

—Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Sketches

Louisa’s first days at the hospital were quiet. This was not to last; soon the first carts arrived, bearing wounded men fresh from a battle.

The ballroom had been converted into another hospital room to accommodate them all. Lined with beds, it was impossible to escape the cries of agony and misery from men—and boys:

“…the situation deteriorated even more when sobbing broke out from the twelve-year-old drummer boy in the corner bed. The boy’s loud lament was for the death of the wounded soldier who had carried him to safety.”

— Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women, Harriet Reisen

Louisa always prided herself on having a strong character, but the suffering she witnessed as she tended to these men revealed that she was human. Her heart hurt as she held the hands of soldiers who knew they would never see their families again.

At some point she found time to write, and produced a poem:

“Beds to the front of them, Beds to the right of them, Beds to the left of them, Nobody blundered. Beamed at by hungry souls, Screamed at with brimming bowls, Steamed at by army rolls, Buttered and sundered. With coffee not cannon plied, Each must be satisfied, Whether they lived or died; All the men wondered.” — Beds to the Front of Them, Louisa May Alcott

Louisa made a special connection with one soldier named John Suhre. He had suffered a gunshot wound to the back from which he would not recover. He had to lie on his back in order to breathe.

She was intrigued by him because, in spite of the pain he was in, he wore an expression of serenity. Her letters suggest that she loved him, though not in a romantic way. She wrote of his “child’s eyes” and how he “seemed to cling to life, as if it were rich in duties and delights, and he had learned the secret of content.”

When Louisa asked the doctor which man in her ward was suffering most, she was crestfallen to learn that it was John. Due to the childlike man’s strength, his was to be a long, painful death.

“You’d better tell him so before long,” she was instructed by the doctor. “Women have a way of doing such things comfortably.”

Louisa stayed near John to provide comfort as the doctor dressed his wound, keeping the dreadful news to herself for a time. It was then that she finally saw tears slide down the patient’s face. Still, he did not complain.

The next time John Suhre’s wounds were dressed, she was turning away when she felt him reach for her.

He said to her, “This is my first battle; do they think it’s going to be my last?”

Louisa finally obeyed the order that the doctor had given her, replying, “I’m afraid they do, John.”

Of his last moments she wrote, “To the end [he] held my hand close, so close that when he was asleep at last, I could not draw it away. Dan [the orderly] helped me, warning me as he did so that it was unsafe for dead and living flesh to lie so long together.”

Louisa also received a bittersweet gift from a grateful soldier:

“After she spoon-fed a New Hampshire man, she accepted a pair of earrings intended for the wife of his dead mate because, he said, she looked so much like the man’s new widow.”

— Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women, Harriet Reisen

Louisa had only served as a nurse for three weeks before she fell ill with typhoid pneumonia.

Ordered by a doctor to bed, she became delirious. In her waking moments, she was aware only of “sharp pain in the side, cough, fever & dizziness.”

The matron of her ward had been diagnosed with the same illness. It was this very matron who made the decision to contact the Alcotts by telegram and inform them of her condition.

Bronson took a train from Concord to Boston and proceeded in the direction of Washington. He arrived at the hospital on January 17.

Louisa, who had resisted with every fiber of her being the thought of giving up, realized upon seeing her father what her family stood to lose if something were to happen to her, the bread-winner. Reluctantly, she agreed to return home.

Three days after Louisa left, the sickly matron who had contacted the Alcotts died of the same disease.

The Civil War produced heroes—not only in the forms of soldiers, but also nurses.

After Louisa returned to Concord, she continued to struggle with her illness for several weeks.

Confined to bed, she suffered from hallucinations. The most terrible was a hallucination that she was in the hospital, tending to wounded soldiers who did not get better.

Her mother and sisters tended to her in turns, until eventually she was coherent again. It was just as they’d feared: Louisa had returned from her volunteer work a changed woman.

The ordeal even changed Louisa physically. When she first became ill and began to hallucinate, the doctor ordered that her long mane of chestnut hair be cut off. Presumably, she had been pulling at it.

This loss devastated Louisa, for her hair was her only feature she liked. She panicked for a time, hoping that it would grow back to its thick glory; later photos show that, fortunately, it did.

Neighbors commented that she was different. Though she maintained her sense of humor, there was something heavy in her eyes. She had seen and heard terrible things; she’d washed the wounds of men who were going to die.

With each amputation she witnessed or heard, it seemed that she lost a bit of herself.

Read also: 10 Greatest Nurses of the Civil War

During her time as a Civil War nurse, Louisa May Alcott was forced to relinquish the innocence she’d held onto during her earlier years as the family struggled financially.

She was a woman changed by the suffering she’d witnessed, haunted by spirits of men such as John Suhre.

Those experiences doubtlessly helped to steel her for the great personal change that was to come.

As her hair grew back—as spring crept in, and the world continued on a drastic path to change—Louisa was on the cusp of becoming a national celebrity.

It would all begin with one book: Little Women.

Author’s Note: If you’re enjoying my articles, consider supporting me as a writer by checking out my historical fantasy novels, The Sea Rose and The Sea King. Book one is currently 99c; book two is $3.99. They are both available on KU! ($3.99 can buy a used book as a resource, so I can continue writing articles for you!) Thank you for your time and continued support!

Lizzie Siddal: The Tragic Life and Death of Art’s First Supermodel

Even those who are not well-versed in art are bound to have seen paintings by members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

This was so interesting to read as I didn't know that Louisa was a nurse in the Civil War. 😊 It is so sad though to think about all the people who didn't make it.🤍

How interesting! The experiences we have certainly shape our lives and our work. I had to look up the dates…Hospital Sketches was published in 1863, five years before Little Women.